When school starts in Rutherford County, Tennessee, this month, and hundreds of teachers return to their physical classrooms, armed with surgical face coverings, Plexiglas shields, and stores of sanitizing supplies, AP English teacher Cassie Piggott will not be among them.

Forced to choose between the career she loves and the health of the child she loves even more, Piggott resigned. She hopes to teach again in the district, after the pandemic ends. For now, she says, she just can’t risk the life of her 9-year-old son, who five years ago received a bone marrow transplant because of a rare immune disorder he still has.

And Piggott isn’t the only one. Across the U.S., in school districts where educators and students are required to return to their physical classrooms, hundreds of educators are reluctantly opting out. When eligible, they're taking early retirements, or using new options for extended leaves that some local NEA-affiliated unions have negotiated for their members. Others are simply walking away.

In a nationwide poll of educators, NEA found that 28 percent said the COVID-19 pandemic has made them more likely to retire early or leave the profession, a rate that could far worsen the U.S.’s shortage of qualified teachers. That number includes a significant number of new or young teachers—one in five teachers with less than 10 years’ experience. It also includes 40 percent of teachers with 21 to 30 years’ experience, who are presumably leaders and mentors on their school campuses, and 55 percent of those with more than 30 years.

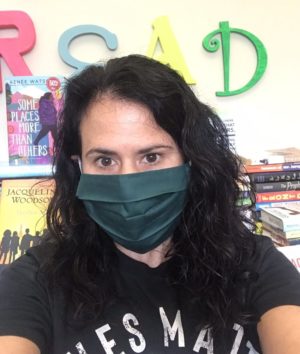

Cassie Piggott (left) hopes to teach again, after the pandemic ends. Until then, the risk of returning to in-person school is too great a risk to her and her family. (photo courtesy Cassie Piggott)

Cassie Piggott (left) hopes to teach again, after the pandemic ends. Until then, the risk of returning to in-person school is too great a risk to her and her family. (photo courtesy Cassie Piggott)

Even more significantly, as the U.S. continues to struggle to diversify its teaching workforce for the benefit of all students, 43 percent of Black teachers say they’re now more likely to retire to leave early. Since the pandemic began, Black and Hispanic people have died at disproportionate rates because of COVID-19.

This is why NEA leaders have been pushing—since the beginning of the pandemic—to reopen schools and campuses only when it’s safe for students, educators, and their families, even as President Trump continues to demand that schools reopen in person.

“Educators and parents want nothing more than to return to in-person instruction, yet the Trump administration has provided no real plan to educators, school administrators, parents, and students on how to reopen school buildings safely and equitably," said NEA President Lily Eskelsen García this week. "Educators believe they are viewed as expendable, and they feel forced to choose between their jobs or the health of themselves and their loved ones."

‘A Plea to Do the Safe and Responsible Thing’

“It kills me to leave, but I think it would kill me—literally—to stay,” says a tearful Pennsylvania reading specialist Ariel Franchak.

Since the pandemic began in the U.S., at least 165,000 people have died—including educators. In Florida, Broward County teacher Stefanie Beth Miller spent two months in the hospital and 21 days on a ventilator because of COVID-19. “I don’t wish this on anyone,” says Miller, who joined the Florida Education Association last week in suing Gov. Ron DeSantis to block schools from physically reopening. The same week they filed suit, they also mourned the death of a 51-year-old Florida sixth-grade teacher from COVID-19.

Within this context, it wasn’t a hard decision to resign, says Franchak. It was a heart-breaking decision, yes. But it was the only decision that made sense to her. “I wanted to work virtually, but I was told to either come to work or resign,” she says. “It was an easy choice for me. I mean the consequences are hard. It’s hard to leave a job that I love so much. But between my health and my family’s health, it was a no-brainer. But it was hard… I’m shaking right now!”

Reading specialist Ariel Franchak resigned in August.

Reading specialist Ariel Franchak resigned in August.

Last week, Franchak returned to her classroom to box up her beloved Jacqueline Woodson novels and hundreds of other of well-loved YA titles, to dismantle her display of Latin and Greek roots, and take down her motivational signs. She hadn’t been in the classroom since March 13, and her spring calendar was still open.

In her resignation letter, which she posted online, Franchak writes:

“This is not just a resignation letter. It is a plea to do the safe and responsible thing. A plea to those [who] have the power to make life altering decisions to make the right choice. You hold the lives of students, teachers and staff in your hands. You have the ability to slow and possibly prevent the spread of a deadly virus. You have the power to save a life, or possibly, many lives.

“Simply put, I am not going into a school to teach 5 days per week, 7.5 hours per day and risk contracting and spreading a deadly virus to anyone, especially my own children, husband, or students. I am not sending my own two children to school for this very reason.

"I love my job as a reading specialist and am extremely passionate about what I do. It hurts my heart to give up something that I love so much. I have stayed up late at night in tears thinking about this. I have spent weeks agonizing over the loss of a job, a job that I don’t even consider ‘a job,’ because I love it so much. To engage students in reading, to help them find books that they love and to help students become lifelong readers—that is my passion. I love what I do so deeply, it feels as though I have lost a part of myself in this process, a part that I am not sure I will be able to get back. But what choice do I have, really?”

A Good Plan May Not Be Enough

After 27 years, Coloradan John Satter is stepping away from his high school classroom this year, through the option of a year-long leave of absence that his local union negotiated for members, Satter told NEA colleagues in a public Facebook group this week.

His district is reopening with remote learning, but transitioning to in-person learning on September 8. This plan only delays the inevitable. Satter fears educators, students, and their family members will get sick, and some will die. "I don't think I am but I genuinely hope I am wrong about the deaths and that the district cares enough to provide a safe work environment," he wrote.

For Piggott, the choice was obvious, as well.

“I have a great principal and he’s doing his best in a crazy situation. He was looking at spreading out my AP students over more periods, trying to keep numbers lower, and I was trying to figure out how to fit 25 students in a room that’s not that big [while maintaining social distancing],” says Piggott. “They have a good plan, but even with a really good plan you’re dealing with children, and families, and how they each perceive the threat of COVID-19.”

Between her AP students who absolutely hate to miss school for any reason at all, and the few parents who may not think COVID-19 is a real threat, Piggott worries the virus could enter her classroom — and consequently her son’s life.

“We’re all human beings,” says Piggot, about her colleagues and her students. “We have to respect and take care of each other.”