For Melodie Henderson, it was one of those “Tag, you’re it!” moments.

“When you’re an educator, often it’s just you and a student at a particular, challenging time in the classroom and you have to step into their world,” says Henderson, a special education teacher at Manchester High School in Chesterfield County, Va.

That’s what happened a few years ago, in the middle of Henderson’s grammar instruction. A student got out of his seat without warning, walked toward the window, and began to sob uncontrollably. Henderson approached the student, who quietly told her that the previous night he had made a deal with the devil, but wished he hadn’t.

“I made a mistake. Give me my soul back!” he shouted. “I don’t need to go!”

Henderson promised him that the school and the school’s staff would keep him safe. Seemingly reassured, he quietly returned to his seat.

This wasn’t the first time Henderson had handled a situation with a student whose behavior demonstratrated a mental health concern. But this particular incident made her realize that the patchwork of resources available to educators in her school and district that were designed to help students who may be grappling with mental illness was—although marginally useful—inadequate.

Henderson dove into her own research into best practices and interventions. Eventually, she developed a workshop geared toward educators who were looking for basic information, tips, and strategies on ways to create a better learning atmosphere for students who have a mental illness. Henderson conducted the workshop at professional development conferences sponsored by the Virginia Education Association.

The workshop only “scratches the surface,” Henderson says, but the educators at her presentations were always grateful for the information.

Ideally, all school districts in Virginia and across the country should be designing and implementing effective, school-based, holistic programs so that individual educators like Henderson don’t have to shoulder the burden of training their colleagues.

Even though educators can be extremely effective in identifying red flags in student interactions and behaviors, says Theresa Nguyen, vice president of policy and programs at Mental Health America, “our teachers are already pushed to the max.”

“It’s best that they be seen as partners—with parents, the administration, the community—in helping students with mental health challenges,” Nguyen says.

“It’s best that they be seen as partners—with parents, the administration, the community—in helping students with mental health challenges,” Nguyen says.

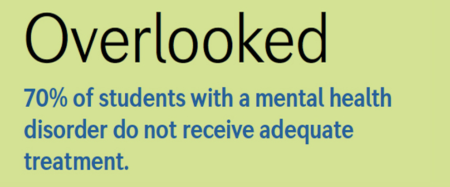

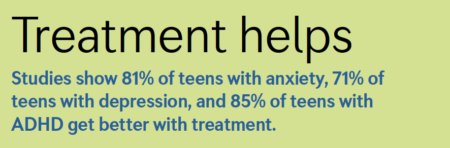

Although Nguyen and others see local and state officials beginning to look more closely at more substantive, evidence-based programs, the U.S. public education system simply isn’t addressing student mental health in a comprehensive way. The magnitude of the problem cannot be overstated. At least 10 million students, ages 13–18, need some sort of professional help with a mental health condition. Depression, anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and bipolar disorder are the most common mental health diagnoses among children and adolescents. And the overwhelming majority of those do not have access to any treatment.

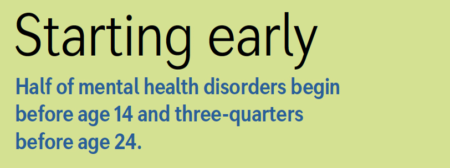

The Child Mind Institute reports that half of all mental illness occurs before the age of 14, and 75 percent by the age of 24—highlighting the urgent need to create systemic approaches to the problem.

“One in five students in this country need treatment,” says Dr. David Anderson, senior director of the Institute’s ADHD and Behavior Disorders Center. “We are seeing a real movement to properly and systematically tackle this crisis, because what these students don’t need is a ‘quick fix.’”

Mental Health in Schools: Stigmas and Culture Shifts

The growing crisis around students’ mental health, and the scarcity of available care, has long been a concern of many educators and health professionals. Interest among lawmakers, however, is a relatively new trend, sparked primarily by the spate of mass shootings. There is also a growing awareness of the stress and anxiety gripping so many teenagers, the role of trauma in their lives, overdue scrutiny over punitive school discipline policies, and the devastating effects of poverty.

It’s the proverbial perfect storm, says Kathy Reamy, a school counselor in La Plata, Md., and chair of NEA’s School Counselor Caucus.

“The public’s natural response is to say we need more mental health services and programs, and we do,” Reamy adds.

But much of the national conversation has been inherently reactive, focusing on “crisis response”—to school shootings in particular—rather than a systematic approach to helping students with their mental health needs.

Crisis management is obviously important, says Anderson, but communities must also understand the devastating impact untreated mental illness has on learning.

“The research is very clear that when a school has a system-based, evidence-based, whole school approach, all students are more engaged academically,” says Anderson.

Such programs differ but they generally provide substantive professional development for staff, workshops, resources, and have social and emotional learning competencies integrated into the curriculum.

According to a 2014 study by the Center for Health and Health Care in Schools, students who receive positive behavioral health interventions see improvements on a range of behaviors related to academic achievement, beyond letter grades or test scores.

“Improvements include increased on-task learning behavior, better time management, strengthened goal setting and problem-solving skills, and decreased rates of absenteeism and suspensions,” the report states.

“Improvements include increased on-task learning behavior, better time management, strengthened goal setting and problem-solving skills, and decreased rates of absenteeism and suspensions,” the report states.

Despite the obvious return on investment, comprehensive mental health programs are still only scattered across the country. Many resource-starved districts have cut—or never had on staff—critical positions, namely school psychologists, undermining their schools’ ability and capacity to properly address these challenges.

While districts may look at hiring more school counselors to fill gaps, Kathy Reamy cautions that their role is often misunderstood. Counselors unquestionably have unique training to help students deal with the social and emotional issues that interfere with their academic success. But real improvement to school mental health programs doesn’t and shouldn’t end with hiring more counselors.

“The services they provide are typically responsive and brief therapy in nature,” explains Reamy. “The misunderstanding of the role of the counselor often either prevents students from coming to us at all or they come expecting long-term therapy, which we simply don’t have the time to provide.”

The stigma around mental health is another obstacle to getting more services in schools. Even if services exist, stigma can prevent students from seeking help.

We’re seeing progress that hopefully will continue. We can’t wait until a student is at a crisis state. Like diabetes or cancer, you should never wait until stage 4 to intervene.” - Theresa Nguyen, Mental Health America

Still, more students are asking for help from their school. “We’re finding that young people are more eager to talk about these issues, says Nguyen. “They hunger for this type of support and conversation and are looking to their school to provide it.”

The fact that schools have become essentially the de facto mental health system for students may be jarring to many educators, district leaders, and parents. As important as the task is, many see it as someone else’s job. The change in perspective is a formidable culture shift for many communities.

“What makes it a little tougher is the need to change how we see students—specifically, thinking less about a students’ belligerent behavior, for example, and more about the reasons for that behavior,” says Joe O’Callaghan, the head of Stamford Public Schools social work department in Connecticut.

But getting there requires training, ongoing professional development, and resources.

“You have to make sure the whole school knows how to support these kids,” O’Callaghan says. “Sometimes what happens is a student will feel a lot of support and encouragement from a social worker. But then they’ll go back into the school and may not receive the same understanding from the teacher, the principal, the security guard, whomever. So in a whole-school program, everybody needs to be relating to and engaging with each other over students who are experiencing difficult things in their lives.”

“Tell Us What You Need”

O’Callaghan helped lead a district-wide effort to overhaul Stamford Public School’s mental health program after three students from three different high schools took their own lives in 2014. The shaken community was galvanized to think about how to improve and support the school mental health programs.

“Just tell us what you need,” a member of the school board asked O’Callaghan after the deaths.

The district always took student mental health seriously, evidenced by a strong team of counselors and school psychologists, plus solid relationships with community agencies.

“We were doing a lot of things right and our team was valued in the community,” O’Callaghan recalls. “But we had to take a step back and think systemically and comprehensively about the work we were doing.”

No small undertaking for a 21-school, 16,000-student school district, with high levels of poverty and a large immigrant population.

Joe O'Callaghan

Joe O'Callaghan

The district hired the Child Health and Development Institute of Connecticut (CHDI) to audit mental health programs. The resulting 2015 report found strength in some areas, but indicated overall efforts had focused on crisis management as opposed to early identification, prevention, and routine care.

This new “continuum of care” is now the central tenant of Stamford’s revitalized program, along with intensive training of all staff in mental health issues and data collection, an area that had been sorely deficient.

The district worked with CHDI to deploy Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS), a school-based program for students grades 5–12, who have experienced traumatic events and are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. The district also implemented a counterpart for grades K–5 called Bounce Back.

By 2017, Stamford Public Schools had expanded the number of evidence-based services for students from zero to four, implemented district-wide trauma and behavioral health training and supports for staff, and integrated community and state resources and services for students.

The goal, explains O’Callaghan, is to create a self-sustaining, in-house program.

“Other districts are outsourcing CBITS to local community agencies who are sending their own social workers into the school. There’s nothing wrong with that model, but we’re training our own staff to create our own institutional expertise.”

“Other districts are outsourcing CBITS to local community agencies who are sending their own social workers into the school. There’s nothing wrong with that model, but we’re training our own staff to create our own institutional expertise.”

Doing so provides a layer of protection against budget cuts or grants approaching expiration.

Even in the face of potential budget tightening, “we’re fortunate to be part of a community that has a long history of supporting what we do,” he adds.

In Chesterfield, Henderson is encouraged by the strides her district has taken, namely the introduction of an SEL curriculum in the lower grades, soon hopefully in the high schools.

“We can always do more, but I think we’re seeing a more proactive, less reactive, approach.”

That shift is a critical first step forward, says Theresa Nguyen, and is indicative of many schools and communities beginning to think about mental health early.

“We’re seeing progress that hopefully will continue. We can’t wait until a student is at a crisis state. Like diabetes or cancer, you should never wait until stage 4 to intervene.”