Voter suppression is real. It undermines our democracy and stymies our quest for education justice.

Research shows that voter suppression in America directly targets people of color, those who are poor, the elderly, and college students. When these groups are excluded from voting, candidates who share their priorities have a harder time getting elected. These constitu-encies are then underrepresented in our local, state, and federal govern-ment and in public discourse—and that directly impacts schools.

Fewer votes lead to fewer resources

Voter suppression only increases the likelihood that we will end up with leaders who don’t know enough about the needs of students of color and low-income students in our public schools. Communities with less representation likely will receive less investment in their schools. These citizens won’t get their say on issues that could boost their students’ prospects, such as: universal preK; curbs on standardized testing; investment in public universities and historically black colleges and universities; local school bonds and school board elections; and Title I funding—which supports low-income schools—and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

Reversing decades of progress

Until the early 1960s, suppression tactics were blatant, including poll taxes, literacy tests, and violence at voter registration offices and polling stations. Thanks largely to the work of civil rights activists, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), which banned

these discriminatory practices and extended voting protections to millions of racial, ethnic, and language minority citizens.

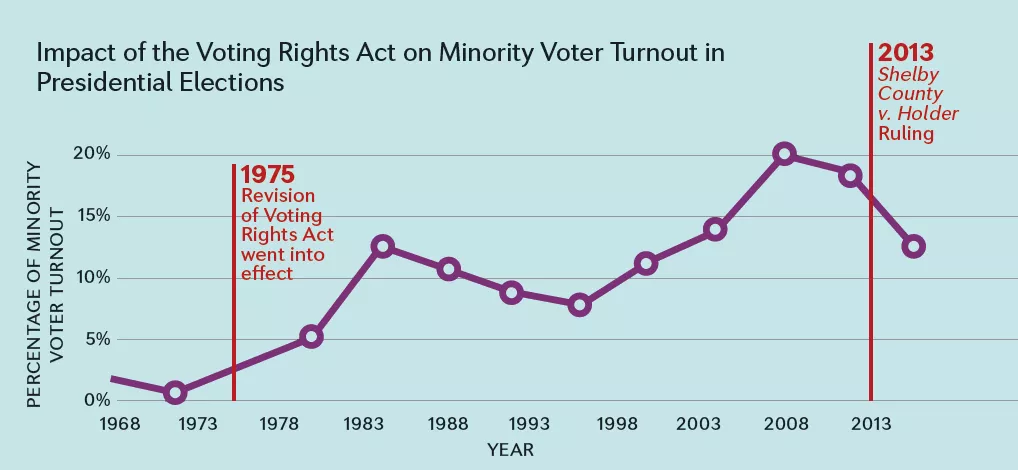

A critical 1975 bipartisan amendment to the VRA strengthened the part of the law that required jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination to pre-clear changes to voting laws with the U.S. Department of Justice. In the decades that followed, people of color participated in elections in record numbers. But more recently, voting rights have suffered. Some law-makers—looking to protect their own seats—have stoked fears that non-eligible voters could cast a ballot or that individuals could vote more than once. These accusations are not supported by research, but have garnered support for more restrictive laws.

A sea change in 2013

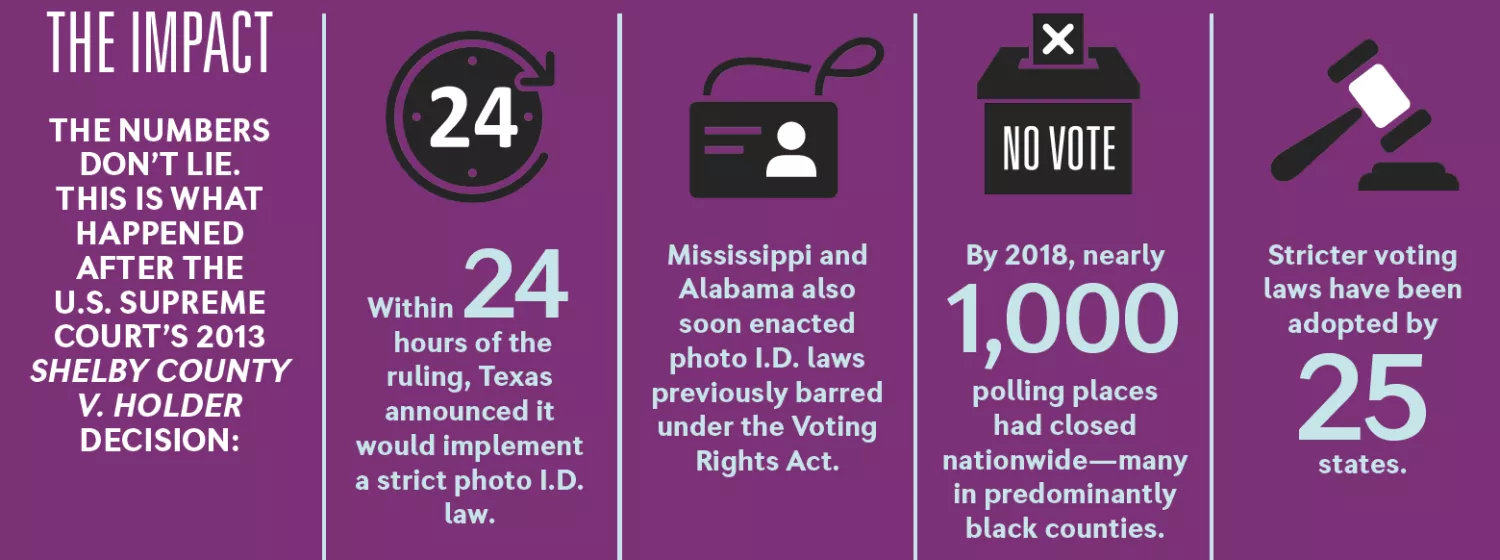

Voting rights were already under siege when the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision Shelby County v. Holder ripped the heart right out of the VRA. The decision meant that states and localities with a history of racial discrimination in voting no longer had to pre-clear changes to voting rules.

After that, conservative-controlled state legislatures went on a voter suppression binge. They shortened early voting, made it harder to register new voters, closed polling places, relentlessly gerrymandered political district maps, and created stricter ID requirements.

Where are we now?

Fourteen states passed new, more restrictive voting laws in time for the 2016 election—the fi rst presidential election since the Shelby County decision. While the exact number of votes lost to suppression tactics is impossible to calculate, an MIT study estimates that at least 1 million eligible voters were unable to cast a ballot in 2016.

The election results: America elected a president who nominated Betsy DeVos—a grossly unqualified secretary of education who has worked against public schools.

In December 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Voting Rights Advancement Act (VRAA), which would reinstate the pre-clearance requirement. At press time, the Senate had refused to take up the bill.

What can we do? Support fair elections and future voters!

1.Write or call your U.S. senator to express your support for the Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2019, which restores voter protections. The U.S. House passed it in 2019. Now the Senate should, too.

2. Demand that your members of Congress support the For the People Act of 2019, a bill that calls for comprehensive protections and improvements to elections that would help every eligible voter cast a ballot and protect elections from cyberattacks and other interference.

3. Volunteer at a voter registration drive.

4. Support smart, state-level proposals that remove barriers to voting, such as: consolidated dates for state and federal primaries; automatic voter registration efforts; early in-person voting; and allowing 17-year-olds to pre-register to vote.

5. Empower students to be informed voters: Register eligible high school students (go to edvotes.org/register-to-vote); pre-register 16- and 17-year-olds; and fight for engaging civics instruction.