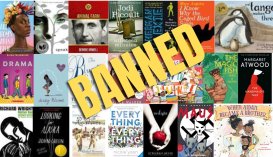

Extremist politicians are intentionally fueling fear and dividing citizens by banning books that represent marginalized people. It is no accident that most of the challenged titles feature LGBTQ+ voices and People of Color.

Often a single parent’s challenge is enough to ban a book from school shelves indefinitely. According to PEN America, a nonprofit that defends free expression, over 1,550 individual titles were banned across more than 33 states during the 2022–2023 school year.

Which states are the worst offenders? Florida, Texas, and Missouri have the most banned or challenged books, according to the report. Many bans are still under review by school districts around the country, but in the meantime, the challenged books remain off-limits.

The freedom to read is under attack, but Aspiring Educators are teaming up with K–12 educators to protect every student’s right to an honest and accurate public education.

‘It’s really heartbreaking’

Alex Johnson (pictured above) is a sophomore at Northern Arizona University (NAU) in Flagstaff, where they are majoring in secondary education in English. Former Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey signed a law, in 2022, that banned several books—including the Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Color Purple by Alice Walker and All Boys Aren’t Blue, a memoir by LGBTQ+ activist George M. Johnson.

Alex Johnson dreams of teaching creative writing to high school students but believes that censorship is stifling students’ creativity and critical thinking.

“The learning comes from the discussion, from the different perspectives, from two kids sitting next to each other that have nothing in common, and finding something in common through a book,” Johnson says.

Growing up, Johnson’s English teachers introduced them to some of their favorite books. Today, some of the books that made them fall in love with literature and inspired them to become a teacher—such as To Kill a Mockingbird and Fahrenheit 451—are banned from classrooms in some states.

“A lot of the censorship comes from people being afraid of the power that words hold and the power that stories hold.”

—Alex Johnson, Northern Arizona University

“It’s really heartbreaking, just seeing all these stories being hidden away as if there’s something to be afraid of,” Johnson says. “I think that a lot of the censorship comes from people being afraid of the power that words hold and the power that stories hold.”

As secretary of NAU’s Aspiring Educators chapter, Johnson shares information about book bans and other advocacy projects with their fellow students.

One of their favorite resources? The New York Public Library’s “Books for All: Protect the Freedom to Read” campaign. The library’s website states: “Stand with NYPL for the right to read freely! We are dedicated to free and open access to information and knowledge—a mission that is directly opposed to censorship.”

People across the country can go online to access young adult books that have been banned or challenged. Johnson hopes that resources like these can help combat politicized attacks on educational and transformative material.

As a creative writer and aspiring novelist, Johnson says, “Stories that need to be told are still out there waiting to be written, and the power of storytelling can never be taken away.”

Books Banned in Public Schools Across the U.S.

During the 2022–2023 school year, there were 3,362 incidents of book bans across 33 states. The highest number of bans took place in Florida, Texas, Missouri, Utah, and Pennsylvania, in that order. (Bans are counted by school district, so one book may account for multiple bans across a state. Source: PEN America)

‘I will protest’

Since Niseiki McFerren moved from Michigan to Florida a few years ago, she has noticed a clear difference in the treatment of educators and in attitudes toward education. A non-traditional student at Florida A&M University, in Tallahassee, McFerren returned to school after earning an associate degree and working in education for more than 20 years—including as a substitute teacher in Head Start programs.

“I have never ever seen education politicized so blatantly, so discriminatorily,” she says. “I think it is shameful.”

In the past two years, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has deliberately limited the educational opportunities of students through laws that ban books, demonize LGBTQ+ students, and whitewash curricula—such as a requirement that history lessons teach that slavery “benefited” Black people.

The book bans and censorship are without cause, says McFerren, who serves as secretary for the Student Florida Education Association.

“It’s because of a made-up agenda. It’s because some people got riled up about something that isn’t true.”

Even her professors have trouble keeping up with state bans that routinely strike popular books from curricula. And McFerren feels her ability to teach is being severely impaired by these policies.

“They’re not doing things to fulfill an obligation to teach our children and to educate them so they can go out into the world and be successful and make good choices. They’re stifling that,” McFerren says. “I don’t know if I can battle that from the classroom, because they’re making it so that I’ll get in trouble.”

McFerren says she is ready to take this fight to the state legislature.

“I will stop what I’m doing and I will be on those Capitol steps. I will march with educators, and I will protest with them,” she says. “Black and brown children want to see their faces on pages as well. Why not? They exist.”

Quote byNiseiki McFerren , secretary, Student Florida Education Association

‘Education is the cure for ignorance’

Student teacher Paulette Vélez Pérez is seeing the impact of Florida’s book bans firsthand.

A senior at the University of Central Florida, in Orlando, she is teaching kindergarten and working with English as a second language students. She finds that fulfilling university requirements to incorporate books into lesson plans and abiding by book bans is increasingly difficult.

“It makes it harder for you to do your assignments or to be able to introduce the books that you want to in the classroom,” she says. Some teachers have removed their in-class libraries, while other schools have gotten rid of libraries altogether.

Under the current legislation, if one parent complains, the book has to be pulled off the shelf, she explains.

As president of her university’s Aspiring Educators chapter, Vélez Pérez protested Florida’s book ban laws during a session at the state legislature where amendments to limit censorship failed.

The review process for book complaints is also flawed, she says: “A book can just be continuously banned over and over again and never actually get reviewed, or the review process can take a year.”

Parents’ input is important, Vélez Pérez notes, but it should not supersede educators’ knowledge and expertise on what and how to teach students.

“I feel personally that education is the cure for ignorance,” she says.

Quote byPaulette Vélez Pérez , student teacher, Florida

Looking for a Banned Book to Read?

Text BANNED to 48744 and receive a book recommendation from NEA!

Learn More