Language arts teacher Kennita Ballard loves her school. The Grace M. James Academy of Excellence, in Louisville, Ky., opened its doors, in 2021, as an all-girls school focused on STEM and Afrocentric studies.

Classes range from sports medicine to engineering to veterinary sciences among other subjects. Lessons center on sisterhood and the contributions of People of Color—including famous and lesser-known figures in history. And educators strive to create a sense of belonging to ensure that students feel valued.

“It’s not enough to say, ‘I’m not racist,’ if your classroom instruction is whitewashed, or if disciplinary practices for being disruptive disproportionately affect Black and brown students,” Ballard says. “The majority of our school [population] is Black and brown, and so we can’t continue to have systems in place that result in them being pushed out of school.”

Instead, the academy uses restorative justice methods. When disruptions occur, educators talk with students and help them reflect on the choices they made and what they could have done differently. If needed, educators and students come together in restorative circles to address harmful behavior and a path toward accountability and repair.

“It’s not a suspension, and it does not go on a student’s permanent record,” Ballard says.

This is not the case in many school districts across the country.

A classic case of systemic racism

A student repeatedly taps a pencil on a desk. Maybe it helps the student concentrate, relieve stress, or remember the lesson. An educator may speak to the student about self-awareness or provide a fidget toy. If the student is Black, an educator may be more likely to view the behavior as disruptive or defiant. This could easily lead to a referral, in-school suspension, or an Individualized Education Program (IEP) for behavior.

“I’ve witnessed several teachers put ‘tapping a pencil on the desk’ in an IEP,” says Shana Balton, a middle school math and social studies teacher, in Wichita, Kan. “I’ve worked in four different schools, and it’s mainly Black boys who are put on behavioral plans. … The IEP can be helpful, but it also can be weaponized.”

If a student transfers to a new school or district, she explains, the IEP follows and shows the previous teachers’ complaints. The information tells the new teacher: This child is disruptive, which could reinforce negative subconscious feelings about boys of color, Balton says.

Before long, a student is trapped in a system that’s intended to help, but instead causes harm. This is systemic racism playing out in real-time.

Systemic racism is a policy, embedded in an organization’s normal practice, that negatively affects a particular group of people, and ripples across other areas of society as well. In this case, it impacts students of color disproportionately and fuels the school-to-prison pipeline.

Yale professor Jayanti Owens designed an experiment to identify disparities in school discipline. She produced videos of White, Black, and Latino teenage male actors performing three identical behaviors: Slamming a door twice, texting repeatedly during a test, and throwing a pencil into the trash can and crumpling a test booklet.

In the experiment, conducted in 2022, more than 1,300 teachers from nearly 300 middle and high schools watched the videos and were asked how they would respond to the incidents.

The findings? Educators were 6.6 percentage points more likely to send a Black student to the principal’s office than a White student.

The study also found that about 25 percent of the difference was driven by the perception that Black boys are more “blameworthy” than White or Latino boys.

This reinforces existing research that shows Black students—particularly girls—are seen as being older and more knowledgeable of adult topics. So they often receive harsher punishments. But these systems can be broken down, Ballard says.

Quote byKennita Ballard , language arts teacher, Kentucky

What is anti-racism?

Racial justice, or racial equity, goes beyond non-racism, says Aaron Dorsey, a national trainer with NEA’s Center for Racial and Social Justice. It’s not only the absence of discrimination and inequities, but also the presence of deliberate systems and supports to achieve and sustain racial equity through proactive and preventative measures.

So what’s the difference between non-racism and anti-racism? “Someone who is non-racist will say: ‘Yes, racism is bad. Everybody should have equal rights and equality,’” Dorsey says. “An anti-racist not only believes in that, but acts to make it a reality.”

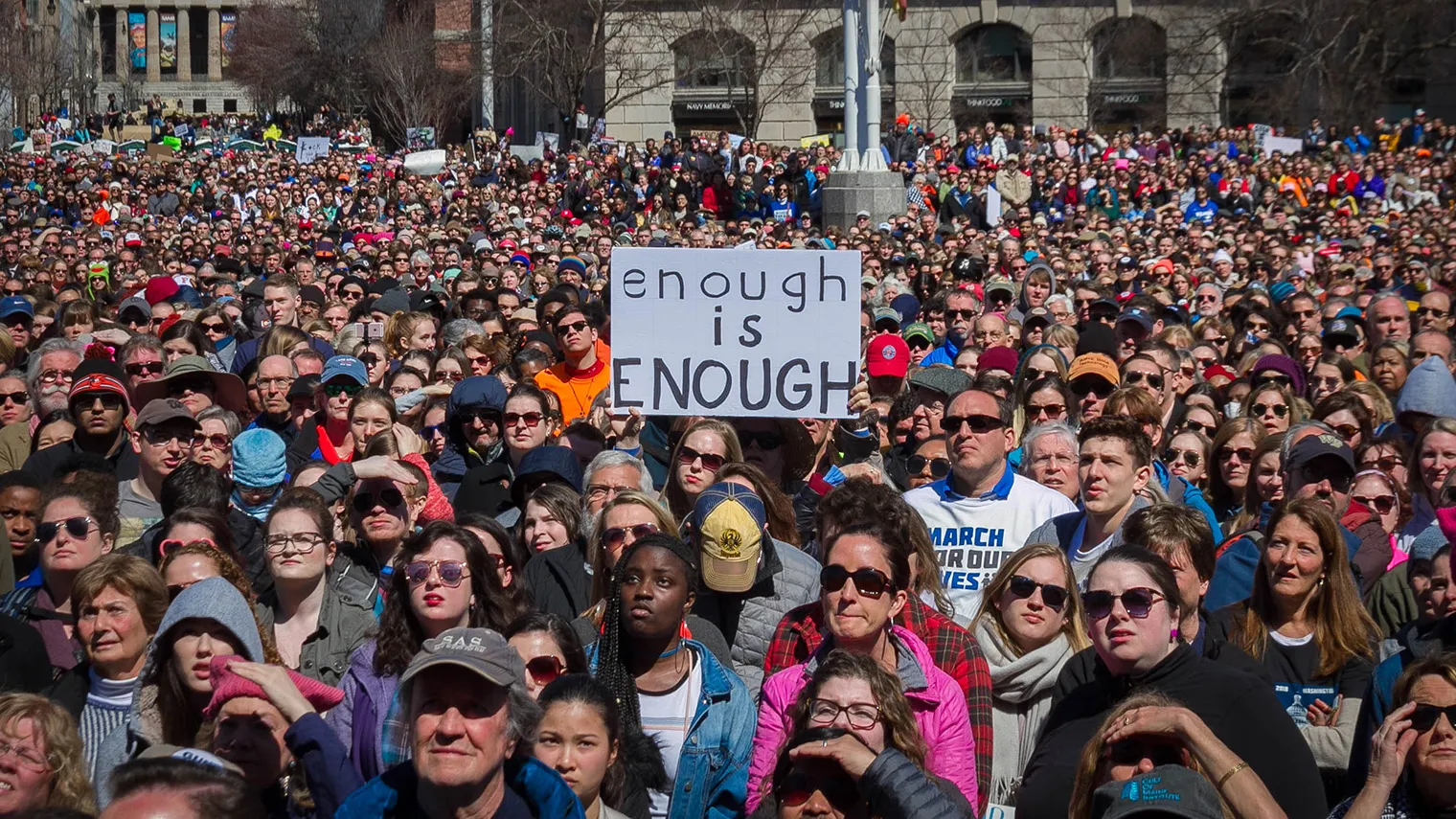

These activists rally on the streets; write letters to elected officials to challenge policies that harm historically marginalized people; or support racial justice organizations financially or by volunteering, Dorsey explains.

“Most people fall into the non-racist category, but anti-racists are doing the work to unlearn racist ideas and calling out racism when they see it,” he says.

What it means to do the work

Ballard and Balton were among 50 educators who participated in an NEA anti-racist training, where participants learned about implicit bias, systems of oppression, anti-racist work, and how to apply the lessons learned in real time.

Ballard says she is now having conversations about race and racism in a way that “calls in” colleagues.

“I don’t get anywhere with less hands as it relates to creating an empowering curriculum, culture, and climate for students. I get everywhere when more hands help break down systems of oppression,” she says.

Balton is working to add more diverse voices to her local union and school board. In November, she was involved in a successful effort to elect People of Color to her local school board, where they can help enact anti-racist education policies.

Quote byBrenda Johnson , Minneapolis educator

Change is possible

Brenda Johnson is a transition specialist at Stadium View, a school inside the Hennepin County Juvenile Detention Center, in Minneapolis. She helps students integrate back into their communities by connecting them with resources and mentors. She also attends court hearings with students and their families.

“We create a space where students can ask the hard questions and feel welcomed and hopeful. Our goal is to keep them out of ‘the big house,’” Johnson says.

As a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Johnson taps into her networks to push for meaningful change for her students and community.

After the 2020 murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, she felt she had to do something to encourage conversations about equity and racial justice. Johnson immediately reached out to clergy at Presbyterian and Lutheran churches with predominantly White congregations.

“We started a dialogue about systems of oppression and racist tactics that are entrenched in this country,” Johnson says. “This is where racist practices can be undone, because it’s going to take more of my White sisters’ and brothers’ help to lead the way. That’s progress.”

Johnson also runs a nonprofit called Shifting Forward, which brings together community groups to build relationships. As part of these efforts, Johnson led a training in 2021 that brought together police officers and members of the Black community in Bloomington, Minn.

“It was heavy,” she says, referring to the conversations that took place. Participants learned how early policing in the South took the form of slave patrols, charged with controlling and disciplining enslaved people. After the Civil War, this legacy lived on as police brutally enforced Jim Crow laws. After the training, one officer told Johnson that she realized she had been harboring racist feelings, and that it was a hard realization

to accept.

But unlearning racist ideas and beliefs is part of the work toward being anti-racist. Johnson says: “It’s about education, calling out the injustice, and showing up, ready to use our voices.”

We can fight for what is best for our students. Explore NEA’s racial and social justice trainings.