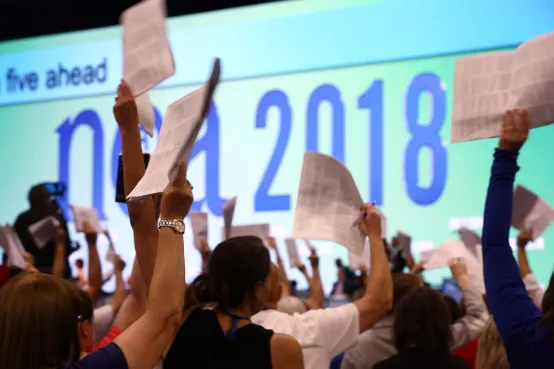

In 2018, more than 8,000 delegates to the RA voted to put racial and social justice at the forefront of NEA’s work. They overwhelmingly adopted a policy commiting NEA to “actively advocate for social and educational strategies fostering the eradication of institutional racism and white privilege.”

In that moment, we were our best selves. We listened, debated, differed — and ultimately, upheld our values of a democratic process and racial justice.

This moment was possible because NEA held those values from our earliest years. We haven’t always made progress as quickly, or neatly. We’ve had to learn and grow. But democracy and racial justice are in our history, and successes from the past give us the strength and stamina to work for a better tomorrow, for all our students.

A Brief History of the NEA

A Brief History of the NEA

Birth of the National Teachers Association

NTA Denounces Slavery

NEA Elects Woman as Vice President

NTA Becomes NEA

The Committee of Ten

NEA Becomes a Representative Assembly

NEA Forms Joint Committee for Justice

NEA Responds to Affiliate Discrimination

NEA Protects Targets of School Segregation

NEA and ATA Merge

NEA Elects First Hispanic President

NEA Elects First Black President

NEA Recognizes the Need for Inclusion and Diversity

NEA Wins at the Supreme Court

NEA Welcomes All Educators

NEA Elects All-Female Leadership Team

NEA Commits to Eradicating Institutional Racism

Educators Continue to Push for Equity

The Birth of NEA (1857-1865)

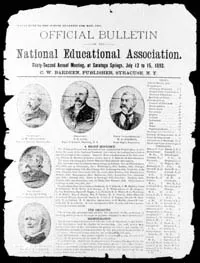

On a summer afternoon in 1857, 43 educators gathered in Philadelphia, answering a national call to unite as one voice in the cause of public education.

At the time, learning to read and write was a luxury for most children—and for many children of color, it was actually a crime. But almost 150 years later, the voice of the fledgling Association has risen to represent 2.7 million educators, and what was once a privilege for a fortunate few is now a rite of passage for every American child.

Over the years, NEA has played an increasingly vital role in improving the conditions under which teachers work and children learn. In the turbulent 1960s, the historic merger of the NEA and the predominantly Black American Teachers Association promoted the human and civil rights of educators and students of all ethnicities.

Today, public schools guarantee every American child a free education, regardless of race or gender, religion or spoken language, social class or disability. And when this diverse group heads to school each morning, dedicated NEA members are there to teach, drive, feed, counsel, nurse—and inspire.

A Single Voice

A hundred years before the birth of NEA, education was largely informal—the main requirements for teaching were the ability to read, write, and stay out of trouble. By the mid-1800s, however, widespread education reforms had led to an emerging public school system and professional training for teachers.

Despite reforms, many teachers continued to work in lonely isolation in one-room schoolhouses with scanty teaching materials, uncertain public support, and salaries of less than $100 a year—sometimes the “salary” was food and lodging.

Who would champion the nation’s teachers? State education associations existed in 15 of the 31 states in the Union, but there was no national organization to serve as a single clear voice for America’s teachers. Until one day in 1857, when 10 state associations sent out “The Call,” an invitation to the nation’s educators to unite.

Although membership in the new National Teachers Association (NTA) was restricted to “gentlemen,” the two women who answered the call were made honorary members and permitted to sign the constitution. This restriction would last for nine years.

The Call

THE 1857 INVITATION TO FORM THE NATIONAL TEACHERS ASSOCIATION:

Believing that what has been accomplished for the states by state associations may be done for the whole country by a National Association, we, the undersigned, invite our fellow-educators throughout the United States to assemble...for the purpose of organizing a National Teachers Association...We cordially extend this invitation to all practical teachers in the North, the South, the East, and the West, who are willing to unite in a general effort to promote the general welfare of our country by concentrating the wisdom and power of numerous minds, and distributing among all the accumulated experiences of all; who are ready to devote their energies and their means to advance the dignity, respectability and usefulness of their calling; and who, in fine, believe that the time has come when the teachers of the nation should gather into one great educational brotherhood...

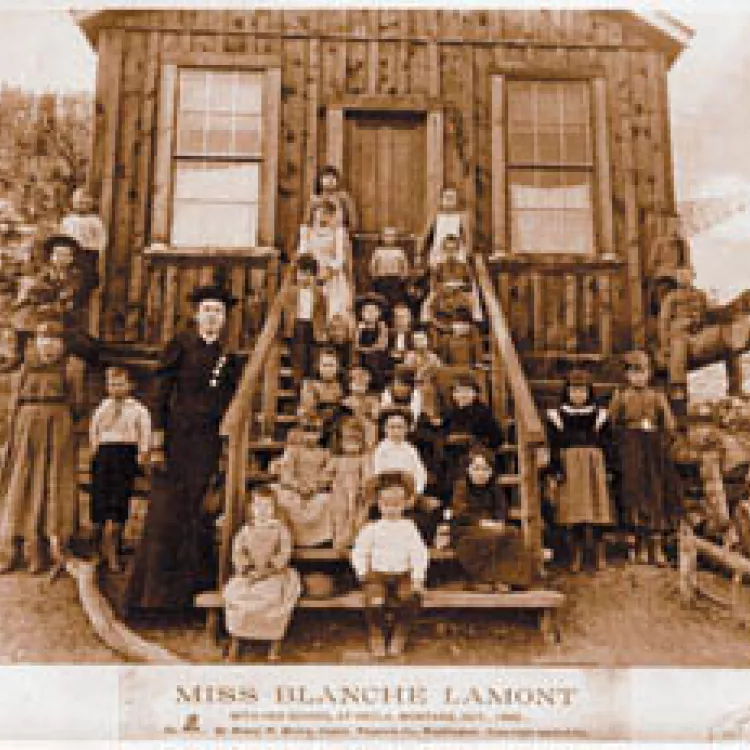

The 1857 invitation to form the National Teachers Association was written by Thomas Valentine, president of the New York Teachers Association.

African American Teachers

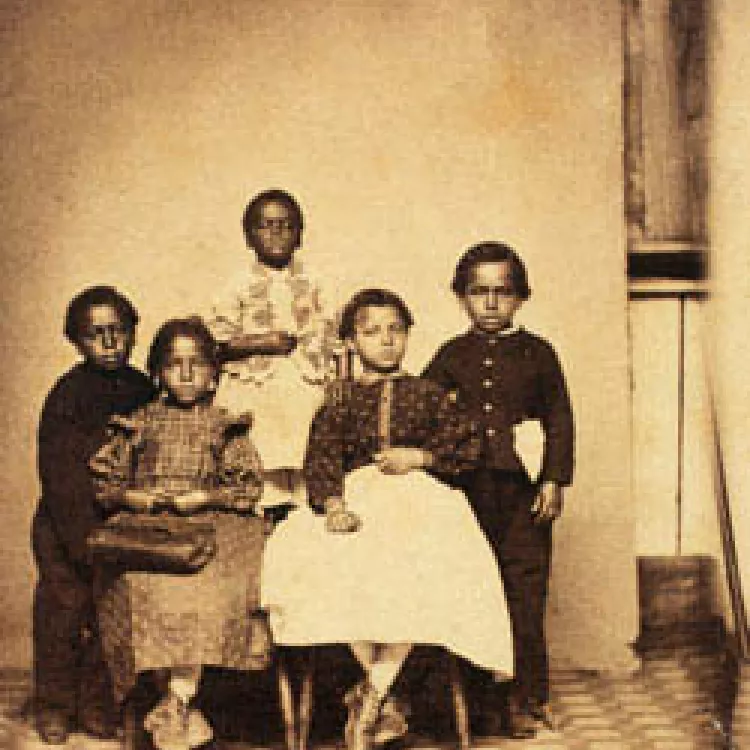

By 1857, half a million free people of African descent lived in the United States. In some communities, “free people of color” had built their own schools. Robert Campbell, the single Black founding member of NTA, taught at the Philadelphia Institute for Colored Children, which educated Black, bi-racial, and American Indian children. Four years after the birth of NTA, 23 Ohio teachers formed the earliest known Black teacher’s association. Members reported salaries of $18 to $50 per month.

Education for people of color was a controversial issue. Some states had established public schools for Black children as early as the 1820s. However, the slaveholding states had outlawed education for slaves, and some states had even outlawed education for free Blacks. Even so, some took risks to learn to read.

The Civil War

In 1861, the issue of slavery dominated the minds and conversations of many Americans. As the quarrel between the North and the South over slavery and other issues worsened, a troubled nation descended into Civil War. The war and its consequences naturally preoccupied the members of the National Teachers Association. During this difficult era, NTA focused on the impact of the war on public education.

Most Americans believed the war wouldn’t last long. But after four long years and over half a million lives lost, the Civil War finally came to an end in the spring of 1865. At that summer’s convention, NTA President J.P. Wilkersham denounced slavery and recommended that no seceded states be readmitted to the Union until they agreed to provide a free public school system for Black as well as White children. The hard work of Reconstruction had begun—for the nation and for its educators.

NEA after the Civil War through the Turn of the Century (1865-1910)

After the War

When the Civil War ended in 1865, the hard work of Reconstruction began for the nation and for its educators. Black and White teachers from the North and South worked to teach newly freed slaves of all ages, as grandparents and their grandchildren sat side by side, learning to read and cipher.

Literacy was so linked to freedom that emancipated slaves were the first to campaign for universal, state-supported schools in the South, a movement many Southerners opposed. During this time, NEA—then known as the National Teachers Association (NTA)—sought federal aid to help

Southern states rebuild their school system and educate the emancipated population. In 1867, the NTA won its first major legislative victory when it successfully lobbied Congress to establish a federal Department of Education to provide and regulate education in the coming years.

The Spirit of Change

Ironically, even though the NTA had been open to minority educators from day one, women had been barred from joining. With the end of the War, however, came a new spirit of egalitarianism that led NTA members in 1866 to open membership to “persons,” rather than just “gentlemen.” Despite the low wages, overwork, and other challenges of the profession, female teachers had more autonomy than practically any other group of women in the 19th century, although many states still had laws barring married teachers. In 1869, just three years after NTA membership was opened to women, Emily Rice became Vice President of the Association—the first woman elected to NTA office.

The very next year, NTA became the National Education Association by absorbing three smaller organizations: the American Normal School Association, the National Association of School Superintendents, and the Central College Association. As a new century began, the growing Association would have a profound impact on education in America.

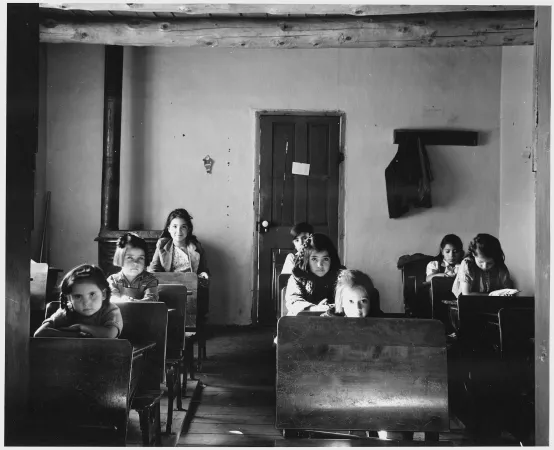

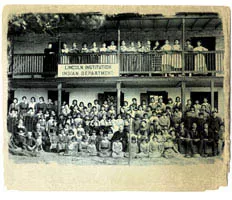

Indigenous Education and Child Labor

NEA continued to address important societal and educational issues of the times. NEA’s Department of Indian Education, established in 1899, researched how the government’s policy of isolating and assimilating the Indigenous nations negatively impacted their education. Indigenous children attended White-run reservation schools, or boarding schools, where they were systematically stripped of their language and culture. Lessons focused on vocational skills and American patriotism.

Child labor was another priority for the Association. Deeply concerned about the disruptive influence child labor had on the health and education of children, NEA worked for years to enact state and federal prohibitions against using children in industry; the address at NEA’s 1905 convention was devoted to this topic. In the decades to come, the combination of compulsory schooling and child labor laws had a huge influence on the number of American children receiving an education.

Turning Fifty

At the turn of the century, teachers were still struggling with perennial issues: salaries remained under $50 a month in most places, and women were still paid less than men. Within their classrooms, teachers often had to educate more than 60 students with little support. At the 1903 NEA convention, fiery Margaret Haley, a Chicago teacher, led a demonstration to bring attention to the need for improving the lot of classroom teachers. In response, NEA created a national committee and allocated funds to work on improving teacher salaries, tenures, and pensions.

By the time NEA celebrated its 50th birthday in 1907, the Association had grown to represent 5,044 educators across the nation. But members were preoccupied by an internal debate: For the first 50 years, administrators had led the organization. As classroom teachers began to dominate the membership, however, they pushed for a greater voice within the Association and in the workplace. In a speech that year, Ella Flagg Young, who would become NEA’s first female president, said: “If the public school system is to meet the demands which 20th century civilization must lay upon it, the isolation...of teachers from the administration of the school must be overcome…can it be true that teachers are stronger in their work when they have no voice in planning the great issues committed to their hands?”

The Birth of the American Teachers Association

In the post-Reconstruction era, segregation permeated life in the North and South, sanctioned by law or local custom. Then, in 1896, the Supreme Court, in Plessy v. Ferguson, upheld legal segregation of schools, which forced Black teachers into a desperate struggle to provide “equal” resources for Black students. The rise of Jim Crow laws would set back the cause of Black education for nearly a century. In 1904, J.R.E. Lee, a prominent Black educator, founded the National Association of Teachers in Colored Schools (NATCS) to offer Black teachers a national forum for discussing and addressing their concerns. NATCS would later become the American Teachers Association.

NEA in the 20th Century (1900-1960)

Salary Strife

In the early 20th century, meager wages remained a critical matter for the nation’s teachers, even though their responsibilities continued to grow. Teachers taught expanded curriculums, fulfilled bureaucratic demands for increased paperwork and testing, and managed multiage classrooms with hundreds of students—many of whom were recent immigrants. A 1909 survey of major cities showed that more than half the students in any given classroom couldn’t speak English.

Teacher shortages grew, as many left the profession for higher-paying jobs elsewhere. In response, NEA formed a commission to study the problem, later issuing a major report that proposed salary schedules to help retain teachers. Based on the report’s findings, NEA renewed its push for a national Department of Education that would help fund programs to reduce illiteracy, train teachers, and equalize education opportunities for all children.

Meanwhile, NEA itself was in transition: It had grown too large to be run on an ad hoc basis by a small group of leaders and whoever showed up at the annual convention. Democratization was needed, as well as more direct connections between the national, state, and local Associations. In 1920, NEA became a Representative Assembly (RA), composed of delegates from affiliated states and locals.

Depression Devastates Schools

Throughout the 1920s, NEA focused on improving teacher pay, establishing retirement pensions, and strengthening a public school system that was rapidly expanding to accommodate a massive influx of students. But on the morning of October 29, 1929, everything came to a halt. The U.S. stock market crashed and the ensuing Great Depression devastated the country, brutally impacting the nation’s schools. As tax revenues shrunk, schools had no money for materials or supplies, and teachers copied texts longhand so there would be enough for students to use. Many schools were forced to close altogether.

NEA’s work was more important than ever. Members visited schools throughout the country, working with the media to focus public attention on the plight of schools. In 1933, NEA became a member of the newly created Federal Advisory Committee on the Emergency in Education. Under the committee’s direction, badly needed assistance and federal aid started flowing to schools.

Joint Committee for Justice

In 1926, a special committee was formed that would expand the scope and mission of NEA for years to come. At the time, many schools—and state Associations—were segregated. The Supreme Court’s doctrine of “separate but equal” had effectively sentenced Black students to unequal funding, resources, and opportunities. The Southern Association of Schools and Colleges (SASC) did not evaluate and accredit Black schools, which blocked Black students from acceptance in many colleges and universities. To address this dire situation and the overall quality of Black education, NEA and the American Teachers Association formed their first Joint Committee. The partnership succeeded—SASC eventually began to evaluate and accredit Black schools.

The War Effort

When America entered World War II in 1941, NEA played an active role in the nation’s war effort, coordinating the rationing of sugar, oil, and canned goods; promoting the sale of Defense Savings Stamps and Defense Bonds in the schools; encouraging students to salvage scrap metal and plant “victory gardens”; and successfully lobbying Congress for special funding for public schools near military bases. This emergency funding helped relieve school districts burdened with financing the education of thousands of military schoolchildren who didn’t add to the local area’s tax base because they lived on federal installations.

NEA also lobbied strongly for the G.I. Bill of Rights to help returning soldiers continue their education. In addition to providing opportunities for individual veterans, the bill would have far-reaching consequences: With more than two million veterans attending college within the next seven years, higher education was no longer a privilege for the elite.

Landmark Decision for Education

In the aftermath of World War II, America’s baby boom saw some 79 million students added to the nation’s public schools. During the 1950s, the United States was, indeed, booming, but not for all: Minorities continued to suffer inequalities in all facets of American life, including public education. Although racial segregation in public schools was the norm, NEA continued to advocate for change. In the previous decade, the Association had refused to hold Representative Assemblies in cities that discriminated against delegates based on race. It had also affiliated with 18 Black teacher’s associations in states where Black teachers were prohibited from joining White organizations.

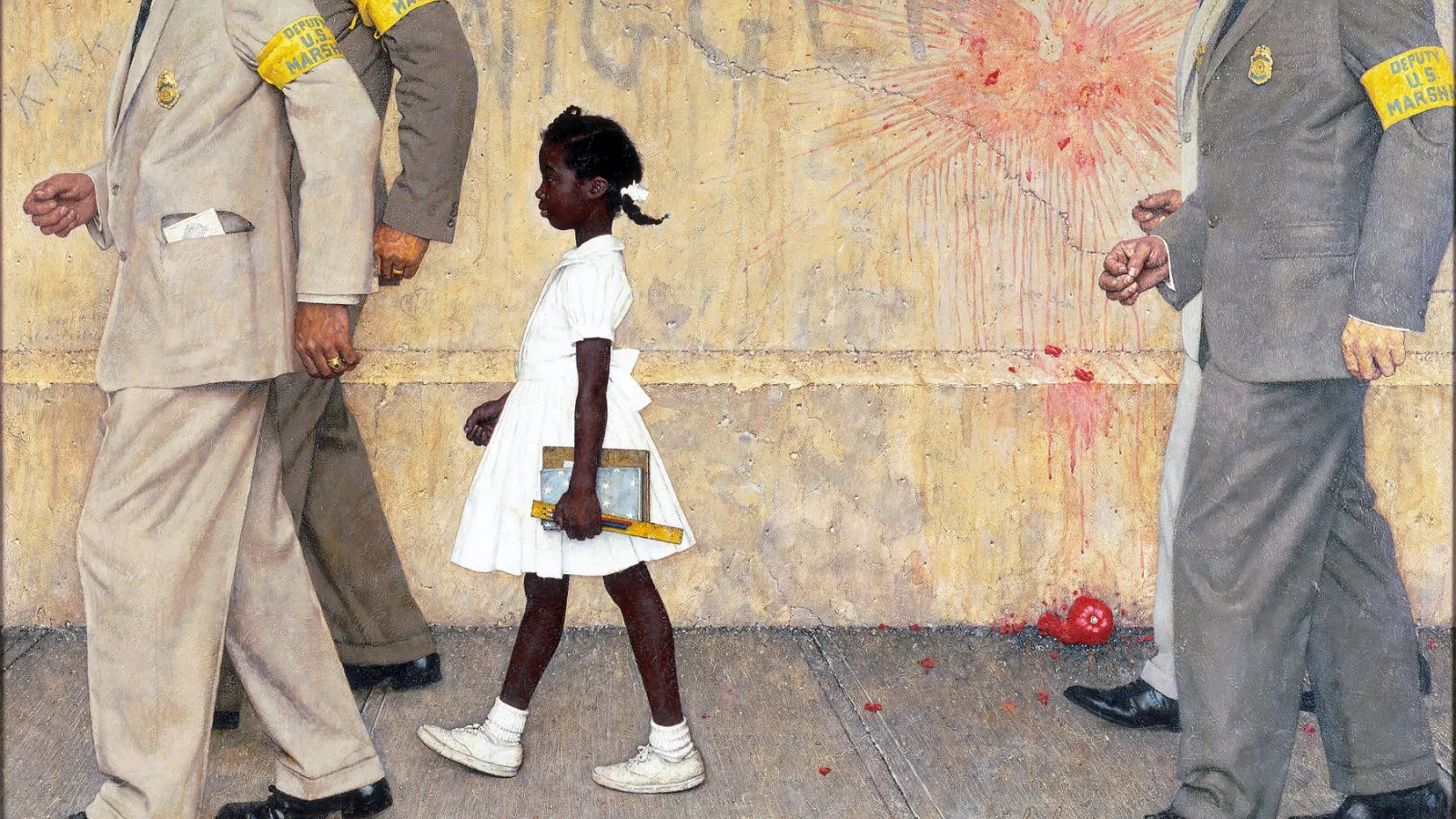

Then, in 1954, the Supreme Court made a landmark decision that became one of the most important events in education and civil rights history. In Brown v. Board of Education, the Court ordered the desegregation of the nation’s public schools, reversing its “separate but equal” doctrine and opening the door to a new era in public education. Black teachers had been largely responsible for financing the case: the American Teachers Association contributed more money to the Brown v. Board legal defense fund than any other single Black organization. After the victory, NEA’s 1954 Representative Assembly urged all Americans to approach integration in a spirit of good will and fair play.

Celebrating a Century!

In 1957, NEA held its centennial anniversary in Philadelphia, the city where it all began. During NEA’s first century, the state Associations focused on the protection and advancement of individual rights, while the national organization worked to strengthen public education, improve the credentialing of educators, and garner more respect for the profession. On its 100th birthday, NEA had over 700,000 members.

Then, two years later, another milestone was reached: Wisconsin became the first state to pass a collective bargaining law for public employees. The passage of this law, the first of many to come, helped usher in an era of teacher bargaining that would transform the Association.

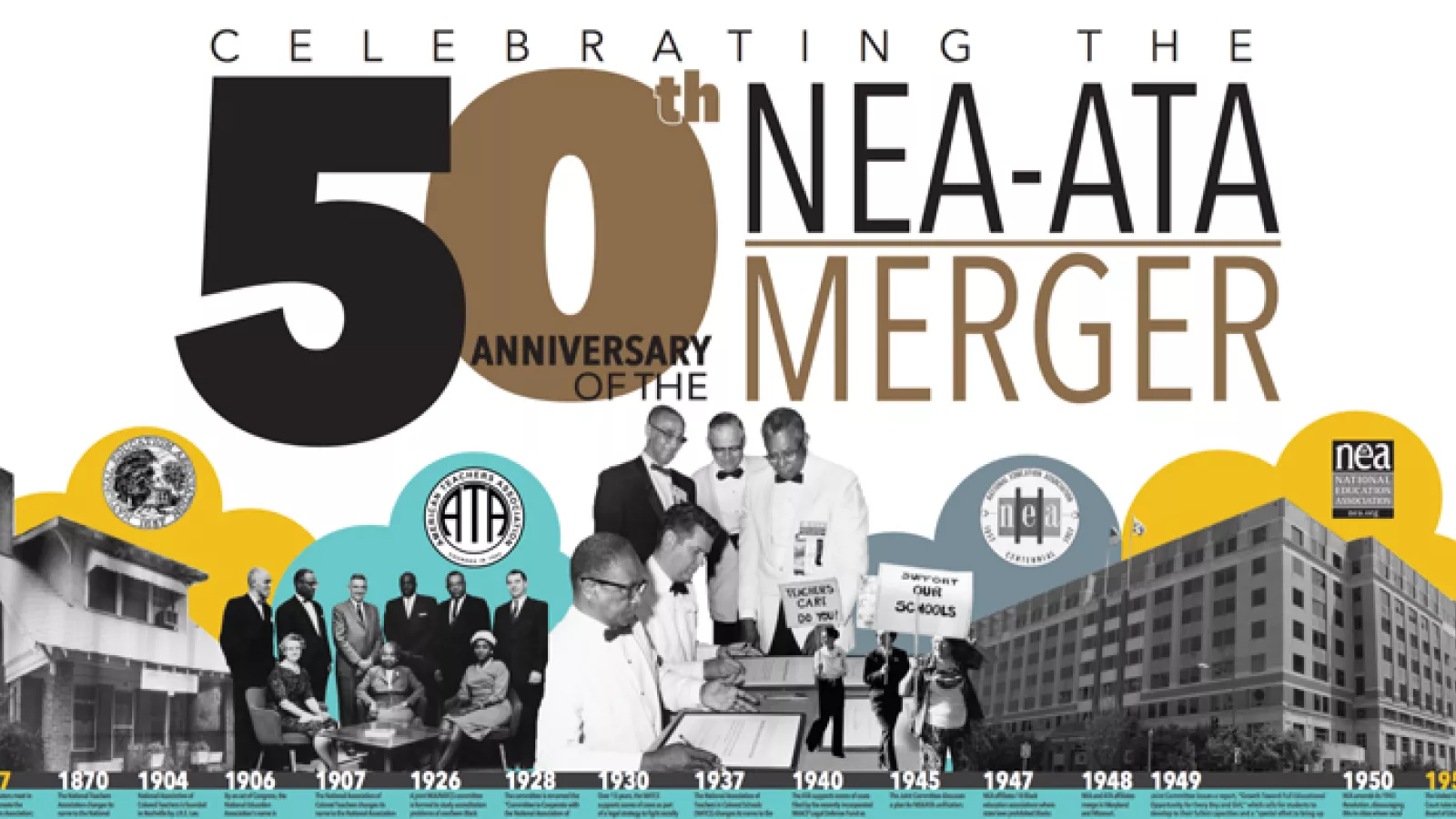

The Legacy of the NEA-ATA Merger (1960-1970)

For over a century, the National Education Association and the American Teachers Association had been on a parallel course for justice and equality for the nation’s schoolchildren—sometimes working together toward a common goal. Last month, we watched as NEA and ATA joined forces to support the Supreme Court’s landmark decision to integrate America’s public schools. In this series’ final installment, we celebrate the historic merger of two great organizations into one single dynamic Association.

Sixties Set Stage for Merger

Even for generations of Americans born decades later, the tumultuous 1960s is an iconic period in the nation’s history. As the decade unfolded, an unbelieving nation witnessed the twin assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and his brother Robert Kennedy, marchers were attacked with tear gas and fire hoses as they rallied for civil rights, college students clashed with police on campuses across the country, and the Vietnam War polarized the nation. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his renowned “I Have a Dream” speech in front of a quarter of a million people at the famous March on Washington, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, and assassinated—all before the decade closed. This period of tremendous social change set the stage for the groundbreaking merger that forever changed the face and course of the National Education Association.

NEA and ATA Join Forces

NEA and ATA started working together as advocates for Black education in 1926, forming a Joint Committee to focus on the evaluation and accreditation of Black schools. The partnership was successful, and by the time the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964, the Joint Committee had spent four decades fighting gross inequities in the treatment of Black schoolchildren and their teachers. Even the Brown v. Board of Education victory proved to be a two-edged sword: When school districts in 17 states used court-ordered desegregation as an excuse to dismiss hundreds of Black teachers, NEA established a $1 million fund to “protect and promote the professional, civil, and human rights of educators.” This fund and the Joint Committee helped support Black teachers who were fired for participating in the voter registration drives that were central to the civil rights struggles of the ’60s. In a yearlong drive, NEA asked each member of the organized teaching profession to contribute at least one dollar to the fund, and teachers across the country came to the aid of their colleagues.

Countdown to Unity

The Joint Committee first discussed a plan to unify NEA and ATA in 1945, but there was adamant opposition from some affiliates and a lukewarm reception from others. At the time, 16 states and the District of Columbia had separate associations for Black and White teachers. Only four states merged affiliates over the next two decades, and in one last effort to unify the remaining affiliates, delegates at the 1964 Representative Assembly passed a resolution requiring racially segregated affiliates to merge. Finally, after years of intense negotiation, NEA and ATA agreed to merge at the 1966 Representative Assembly.

A Historic Merger

The dramatic and heartfelt merger ceremony took place in Miami Beach, where 13 years earlier NEA had relocated the convention when the city assured them it would not discriminate against Black delegates. The lights in the great convention hall dimmed to darkness as spotlights focused on five men at a small table on the stage. As the presidents and executive secretaries of NEA and ATA signed a Unification Certificate, delegates sang “Glory, Glory, Hallelujah,” then erupted into a prolonged standing ovation. Preserving an ATA tradition, NEA continued to hold a Human and Civil Rights Awards Program to honor individuals and affiliates who expanded educational opportunities for minority students and educators.

Fit to Teach, Fit to Vote

The NEA-ATA Joint Committee sent leaders and staff to help teachers in Selma, Alabama, launch a voter registration campaign for Black educators under the slogan, “Fit to Teach, Fit to Vote.” The teachers’ campaign provided an opening spark for the voter drives and famous five-day civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery led by Martin Luther King Jr. The national media covering the historic 1965 march set up headquarters at the Alabama Education Association.

The Struggle Continues

Neither the Association nor the country changed overnight. Battles continued to be fought as some affiliates resisted unification, and widespread dismissals and unfair treatment of Black educators persisted. In some communities, schools were burned to prevent desegregation, and many Black students were expelled and injured—even killed. But NEA was able to work more vigorously on behalf of true unity, within the organization and in the schools. NEA set a timetable for the remaining affiliates to merge and met with NAACP Legal Defense Fund lawyers and the U.S. Office of Education to develop short- and long-range plans to halt the abuse of teachers and students.

Teachers and Students March

On the march to Montgomery, NEA staff reporter Howard Carroll interviewed a high school senior who was among the teachers, students, and clergy assaulted for participating in a voter registration rally in Selma a few weeks before.

I went down to Selma because the teachers, our Black members, played such a big part in the civil rights movement. When I went into the schools and talked to the teachers, I saw the stark differences in their circumstances. It was a tragedy to think that people who were our members were denied the opportunities White educators had. A few weeks before the final march to Montgomery, many teachers had been assaulted when they tried to march across the Pettus Bridge. The march had to be halted because the marchers were overcome by tear gas.

A Powerful Legacy

The merger between NEA and ATA had long-term implications, not only for Black teachers and students, but for other minority populations, including women. Three months after the merger, NEA sponsored a major conference on bilingual education and the needs of Spanish-speaking students. The NEA conference led directly to the passage of the 1968 Bilingual Education Act—a great legacy for Braulio Alonso, who became NEA’s first Hispanic president in 1967.

In 1968, Elizabeth Duncan Koontz was elected NEA’s first Black president, and NEA established the Human and Civil Rights Division. Committed to helping civil rights law and rhetoric become reality, the Division tackled a variety of issues affecting minority education. Over the next decade, NEA created working task forces that later morphed into four caucuses representing a range of racial and ethnic minorities.

As America’s classrooms grow more racially diverse, the merger that took place 40 years ago has grown more significant and noteworthy. From its inception in 1857—when NEA welcomed Black members four years before the Civil War—to the merger with ATA during the height of the civil rights struggles, the Association has been ahead of its time, crusading for the rights of educators and the children whose lives they touch.

Stay Informed We'll come to you