On June 4, 1991, Minnesota passed the nation’s first charter school law, leading to the opening of City Academy in St. Paul one year later. Within a decade, more than 40 states would have their own laws authorizing charters to set up shop in school districts. And now, 25 years later, 7 percent of all U.S. students - almost 3 million total - are now attending charter schools.

On June 4, 1991, Minnesota passed the nation’s first charter school law, leading to the opening of City Academy in St. Paul one year later. Within a decade, more than 40 states would have their own laws authorizing charters to set up shop in school districts. And now, 25 years later, 7 percent of all U.S. students - almost 3 million total - are now attending charter schools.

Often considered the crown jewel of the education reform movement, charters have faced heightened scrutiny in recent years, and it's fair to say that the brand has taken a bit of a beating. Whether it's extreme financial mismanagement, punitive and unfair disciplinary policies, questionable enrollment practices, or exaggerated reports of academic success, the charter sector's record is (finally) on display.

But will new calls for greater accountability steer us away from the unfettered expansion of the last 25 years, or will charter schools continue to grab larger chunks of market share in school districts across the country? That was one of the questions addressed at a recent panel discussion held at the Center for American Progress (CAP) to mark the 25th anniversary of Minnesota's landmark charter school law.

Moderated by Catherine Brown, CAP vice president of education policy, the panel featured Leo Casey, executive director of the Albert Shanker Institute, Shantelle Wright, founder and CEO of Achievement Prep, a charter school in Washington D.C., Richard Kahlenberg, senior fellow of the Century Foundation, and David Osborne, director of the Reinventing America’s Schools Project at the Progressive Policy Institute.

Casey began by reminding the audience that the original vision for charter schools – first articulated by Albert Shanker in the late 1980s – is now more or less non-existent in the sector today. The two pillars of that vision were, one, charters should be a place for innovation that could be shared with traditional public schools, and, secondly, teachers, parents and community members would be empowered to try out new ideas and actually play an active role in school decisionmaking.

"But 25 years later, the reality is that this has happened in only a minority of charter schools," Casey said. "Most use a very traditional curriculum, a very traditional pedagogy, rely upon stringent discipline policies. And most charters don't have avenues for parent voice. Being a "consumer" is not real voice. And there are no avenues for teacher voice either."

The successful charter schools that are innovative and do empower educators and parents "represent the exception, not the rule,” he added.

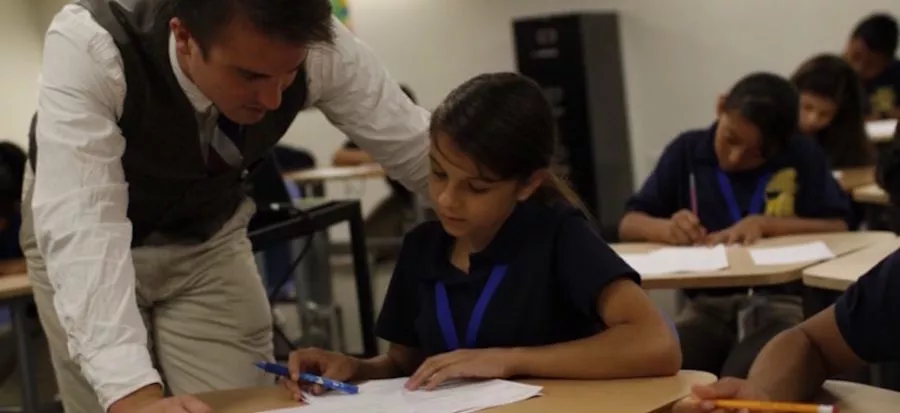

Students line up at a No Excuses charter school in Chicago. The No Excuses model has come under fire recently for its overly strict discipline regimen.

Students line up at a No Excuses charter school in Chicago. The No Excuses model has come under fire recently for its overly strict discipline regimen.

Misinterpreting Results

David Osborne, a longtime charter school advocate, disagreed with Casey's assessment and held up KIPP schools - the leader of the "No Excuses" movement - as models of innovation. As an example, Osbourne pointed to the practice of assessing students every six weeks, 1:1 laptop initiatives, and the prevalence of blended learning.

"Traditional public don't do that. No Excuses schools do," Osborne said.

Shantelle Wright of Achievement Prep, while making it clear she wasn't there to defend all charter schools, argued that critics have been using a "broad, sweeping brush" to exaggerate problems in the sector. The bottom line, Wright said, is that "charter schools are delivering" for students in high-poverty districts.

But what are they delivering? Richard Kahlenberg believes that while charter schools have helped "put lie to the idea that low-income students can't achieve at high levels," he cautioned that that the success we read and hear about - particularly in regards to KIPP - has been misinterpreted and maybe a bit overhyped.

"At some charter schools, not a majority of them, we have students doing exceedingly well," Kahlenberg said. "But there's a lazy and reactionary interpretation which says, 'Ok, if a KIPP school, for example, has a high level of segregation and high numbers of low-income students, then poverty and segregation must have very little effect on achievement.'"

Kahlenberg also pointed out that some may look at these same schools and conclude that reducing collective bargaining and ignoring teacher voice helps improve student outcomes. "These are both simplistic interpretations and are very wrong," he said.

Needed: Diversity and Teacher Voice

KIPP schools, Kahlenberg added, "actually kind of brag that they are segregated. But half a century of academic research suggests strongly that this is not an ideal model for educating kids. Now many KIPP students are in college, in institutions that are perhaps more economically and racially integrated, and they are struggling."

It's a growing problem summed up in a recent report by the Civil Rights Project at UCLA: "The charter movement has been a major political success but it has been a civil rights failure." In addition, the strict behavior rules that embody the No Excuses model have faced a backlash in 2016, forcing many charter schools to rethink their approach to discipline.

The panel also discussed the ongoing problem of teacher churn, or the high attrition rates that have afflicted the charter sector.

The children that charter schools serve – the poor, Black and Brown kids in inner cities – deserve better.

- Leo Casey, Albert Shanker Institute

"What we have for the most part in charter schools is a Teach for America model," Casey said. "The majority of TFA graduates are being sent to charter schools and they haven't mastered the craft of teaching. Charters are churning these teachers over and over. It's an educational model as well as an economic model."

It is an issue that directly affects innovation and outcomes, Casey added, because if teachers are always learning on the job, then you're going to rely disproportionately on scripted curriculum.

"They don't know how to engage their students in active thinking. The children that charter schools serve - the poor, Black and Brown kids in inner cities - deserve better," Casey said.

Asked to look ahead at what the next decade will bring the charter sector, Osborne responded that growth will continue unabated.

"If charters are serving almost 3 million students now, according to the data, that number will double in six years. And 10 years from now there will be somewhere around 9 million," Osborne predicted.

Kahlenberg believes more data and reasoned analysis about the sector's successes and failures will emerge, leading to smarter policies and practices. Topping this list is greater attention to diversity and teacher voice. Kahlenberg conceded that, of the two, the campaign to give charter educators the right to organize is the steeper climb, but remains essential to make the schools more successful. Still, Kahlenberg sees a course correction for charter schools in the offing.

"In education, we tend to see these swings of the pendulum. We've gone to one extreme and now we're beginning to move back toward the center."