For the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), it all came all down to a financial settlement—a payment of $6.4 million from Pearson Education, announced in September 2015. This was hardly the desired outcome two years earlier when the nation’s second largest school district launched an ambitious $1.3 billion plan to put an iPad in the hands of each of the district’s 650,000 students. The goal? To “revolutionize” learning, of course. Instead, the highly touted initiative quickly imploded, and rather than becoming a model for integrating education technology in the classroom, the effort became a cautionary tale of exactly what not to do.

From the outset, the initiative was crippled by problems. The preloaded Pearson curriculum was full of glitches. Students hacked into the devices. The Wi-Fi infrastructure was inadequate. And, perhaps most critically, there was a dire lack of teacher training.

Tom Daccord, founder of EdTech Teacher says the overriding problem was much more fundamental. The district never answered one simple question: Why?

“Districts must have a strategy and vision of what they want the technology to achieve. And you have to first address how any new device will be integrated in a meaningful and purposeful way in the classroom. LA Unified failed to do so and the initiative quickly crumbled.”

The district is still dealing with the fallout of the iPad debacle, says Alex Caputo-Pearl, president of United Teachers of Los Angeles (UTLA), including an FBI investigation into the close ties between former superintendent John Deasy and Apple.

The troubled iPad initiative was one of the mishaps that led to the resignation of LAUSD Superintendent John Deasy in October 2014. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, File)

The troubled iPad initiative was one of the mishaps that led to the resignation of LAUSD Superintendent John Deasy in October 2014. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, File)

“But there’s also a lesson to be learned from fast-tracking technology purchases without the meaningful involvement of classroom practitioners,” says Caputo-Pearl. “Without teacher input from the get-go, you risk ending up with high-priced products that don’t serve the classroom.”

Los Angeles isn’t alone. District officials and policymakers across the country just can't resist the allure of the latest “next big thing” or “game-changer” for the classroom. What often emerges - at the expense of students and educators - are half-baked plans and reckless spending sprees designed to get new devices into the classroom quickly. The ensuing failures have provided grist for techno-skeptics’ claims that the transformative potential of digital technology is overrated. Most would agree about the hype surrounding education technology, but there's also a risk of rejecting out of hand the potential these tools hold.

“Will these devices transform your classroom if your district doesn't have a strategy and a real plan? Probably not,” says Jennifer Harmsen, a social studies teacher at Hillsborough Middle School in New Jersey. “But I think we have a responsibility as educators to find ways to make these tools work in our classrooms. Otherwise, I think we’re remiss in doing what's best for the students.”

Harmsen's advice for schools? “Tread carefully and slowly and learn as you go along. And never forget that the question to answer at every step is: What do you want the students to achieve?”

Buy Now, Ask Questions Later

Erin Samuels, a second- and third- grade teacher at Wilshire Park Elementary in Minnesota, can’t imagine teaching without a tablet. She firmly credits the iPad with improving end-of-year assessments in math and reading for the small cluster of ELL students she taught during the 2013-14 school year

“[iPads] put a teacher in the palm of their hands when I wasn’t able to work with them directly,” says Samuels. This came after the class as a whole would read a text together. When it was time to check comprehension, the ELL students were obviously at a lower level, so Samuels would have them work independently for a time with the iPad using various apps that bolstered their understanding.

According to some estimates, more than $10 billion is spent on education technology every year. (AP Photo/The Casper Star-Tribune, Tim Kupsick)

According to some estimates, more than $10 billion is spent on education technology every year. (AP Photo/The Casper Star-Tribune, Tim Kupsick)

“I think it made them more comfortable in the classroom and they knew they had to do something different from the other kids,” says Samuels, now in her seventh year of teaching. “They were engaged and even kind of proud because they got to spend more time on the device than the other kids. It helped them grow as learners.”

Wilshire Park Elementary does not have 1:1 student-to-iPad access—far from it. Samuels will have at most three iPads to work with in one class. “The money’s not there, but we make due with what we have,” she says resignedly.

But something is clearly working in Samuels’ class, and if her district were to purchase thousands more tablets, she would be well-prepared. That is, if the roll-out was methodical, if logistical issues were addressed, and if educators like Samuels were active participants at all points in the process.

Some districts have taken it slow on expensive 1:1 programs, eager to avoid pitfalls that have derailed others, and not entirely convinced that the educational return matches the investment. This is wise, says Patricia Burch associate professor of education at the University of Southern California and author of Equal Scrutiny: Privatization and Accountability in Digital Education. The available research, which is not extensive, indicates that digital technology has not yet bolstered student achievement—at least not to an extent that justifies the enthusiasm shared by many policymakers and district officials.

If districts don’t build in the capacity ... and invest in professional development so all teachers know what it means to integrate technology into the classroom, the program is going to double back on you.

The central question, however, isn't if a device like a tablet can enhance learning, Burch cautions. The question is under what conditions.

“A lot of districts have bought all this stuff without answering these questions. It’s not necessarily that they don't want to learn. It’s just that they’re always under pressure to do something quickly and often.”

“Teachers have to be central,” says Burch, “If districts don’t build in the capacity, [and] the necessary supports, and invest in professional development so all teachers know what it means to integrate technology into the classroom, the program is going to double back on you.”

A 2014 UTLA membership survey, for example, found 75 percent of teachers did not believe LAUSD provided adequate training to help them integrate the iPads into the curriculum. The district’s message to educators in a nutshell was, “Here are the tablets, so go at it. We can’t wait to see the magic happen.”

“That’s not the kind of classroom autonomy teachers are looking for,” says Tom Daccord.

At Hillsborough Township Public Schools, educators were central players in the district’s efforts to determine whether to use tablets at all. During the 2012–13 school year, a pilot team used iPads and Google Chromebooks—a cheaper, more basic laptop—with students. To determine which tool was best for learning, teachers, students, and parents were asked for feedback.

The district’s measured, cautious approach toward education technology gave educators the time and resources they needed to properly evaluate the two devices, says Hillsborough Middle School’s Jennifer Harmsen, who participated in the project.

“There was no rush to get any particular tool in the classroom. Our intention was to just get it right,” she explains.

Hillsborough Middle School teacher Jennifer Harmsen was part of a team that evaluated both the iPad and the Chromebook.

(Photo: Norman Y. Lono, 2015)

Teachers gave high marks to the iPad and the Chromebook, but felt the latter had key advantages, including a relatively low cost. The built-in keyboard and lower-demand tech support was also attractive. Educators also said that students generally associated the iPad with fun and gaming, while Chromebooks look more like a learning tool and therefore would be less of a distraction. In the fall of 2014, Hillsborough distributed 4,600 Chromebooks to students and sold the iPads.

No Replacement for a Qualified Educator

For Dr. Daryl Adams, superintendent of California’s Coachella Valley Unified School District, it’s always been about the iPad. Part of a rural desert area about 150 miles east of Los Angeles, Coachella Valley is one of the nation’s poorest districts, with almost 100 percent of its 19,500 students on free-or reduced lunch and a significant percentage undocumented.

Adams views access to digital technology as a civil rights issue, and says socioeconomic status should not be a barrier that prevents every student from having a school-supplied iPad. In 2011—his first year as superintendent—Adams began laying the groundwork for a 1:1 iPad initiative.

We have to do a much better job at making sure the discussion is about learning. With education technology, we really don't want to be stuck in the either/or paradigm.

“Our school system was not preparing our students for a prosperous future,” Adams says. “A 21st Century school system must be connected and provide a holistic education for all students. We wanted students to have 24/7 access to knowledge and information, so they can communicate with their teachers and colleagues, they can create and produce and display information and presentations, they can research and explore.”

Widely known for his infectious enthusiasm, tenacity, and passion for education technology, Adams was determined to involve school staff and the community in all aspects of the program, making it markedly easier to galvanize support in the community and navigate the logistical issues associated with a 1:1 program.

Educators in Coachella were quick to sign on, says Richard Razo, president of the Coachella Valley Teachers Association, and were instrumental in lobbying support for the $42 million technology bond initiative to fund the purchase of the devices and upgrade the district’s infrastructure.

“We went door-to-door talking with parents and other members of the community,” Razo says. “We knew that without this bond, the program would have never gotten off the ground. But once the community heard about what the district was trying to do, they got behind it overwhelmingly.” The measure passed in November 2012 with a 67 percent majority vote. During the 2013–14 school year, Coachella equipped every student with a new iPad.

“These devices cannot take the place of a qualified educator,” says Rebecca Flanagan, a library media teacher at Desert Mirage High School.

“But the iPads have redefined the way education looks in Coechella. We are moving away from the teacher being the distributor of knowledge in a class, to a facilitator of how to access and use that knowledge. No longer must students memorize facts when they are at their fingertips; now they must learn how to utilize what is so readily available,” Flanagan says.

CVTA is working with the district to hopefully improve access to teacher training, which has generally been limited to after school and weekends. The goal in the next school year is to implement an early-release day during the week so educators can receive professional development during school hours.

The Coachella iPad program was funded by a $42 million technology bond initiative, overwhelmingly approved by the community. (Photo: Coachella Valley Unified School District)

The Coachella iPad program was funded by a $42 million technology bond initiative, overwhelmingly approved by the community. (Photo: Coachella Valley Unified School District)

“We still have a lot of work to do to make the program work even better,” Razo says. “But I can’t tell you what it's like to see these kids— many of them can’t even afford books—with their own iPad. This has already made such a huge difference in our community.”

Connectivity is an ongoing challenge, since many lower income student don’t have Internet access at home. Without it, digital devices are rendered fairly useless, contributing to what the Department of Education has called the “homework gap.” Coachella Valley got creative. Routers were placed on school buses to enable students to do homework coming and going from school. The buses, when not in use, are parked in remote areas so students in those neighborhoods could have some degree of access outside of school.

Pres. Barack Obama applauded Coachella’s program at a 2014 White House ConnectEd Conference. “This is really smart. You've got underutilized resources — buses in the evening — so you put the routers on, disperse them, and suddenly everybody is connected,” Obama said.

Ultimately, however, these and similar efforts represent merely a patchwork of innovative programs. Nationwide, lack of connectivity for lower-income students remains a serious issue—one that is too often ignored when districts rush to bring tablets into their classrooms. Inequities widen when technologies are increased too rapidly, says Patricia Burch. She questions whether enough districts, even in the aftermath of the highly-publicized LAUSD fiasco, are thinking through this and other issues. “I’m not seeing it. And there are always new products and services around the corner that they will be pressured to buy.”

Digital tools like iPads can help create powerful learning environments, so it’s frustrating that districts fail to communicate why they’ve made this major investment, says Tom Daccord.

“There are already enough educators who don’t believe these tools support good teaching, so we have to do a much better job at making sure the discussion is about learning. With education technology, we really don't want to be stuck in the either/or paradigm.”

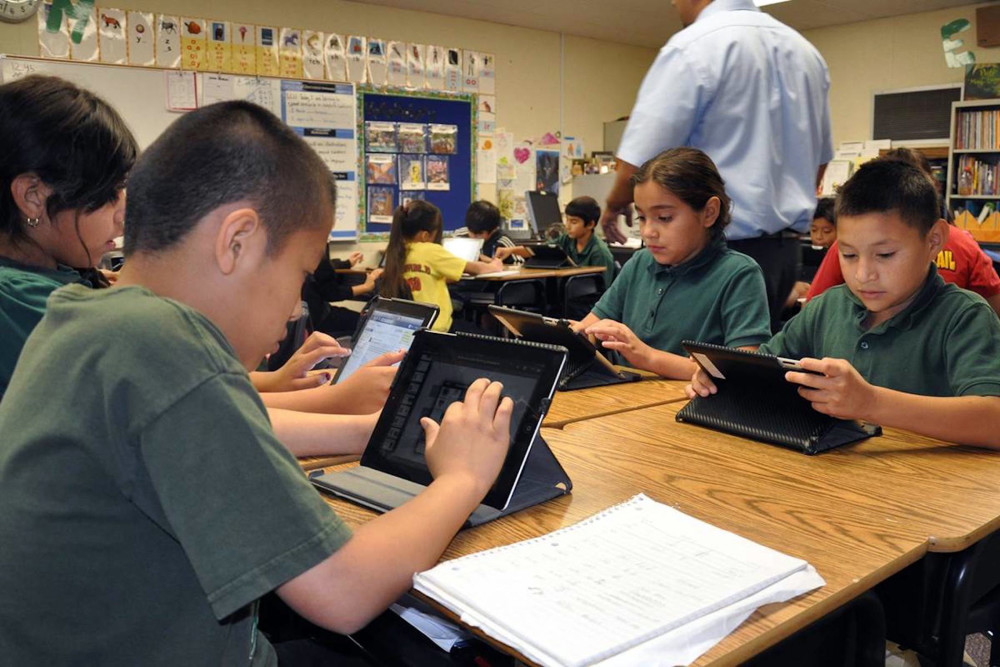

Top photo: Brad Flickinger/Creative Commons