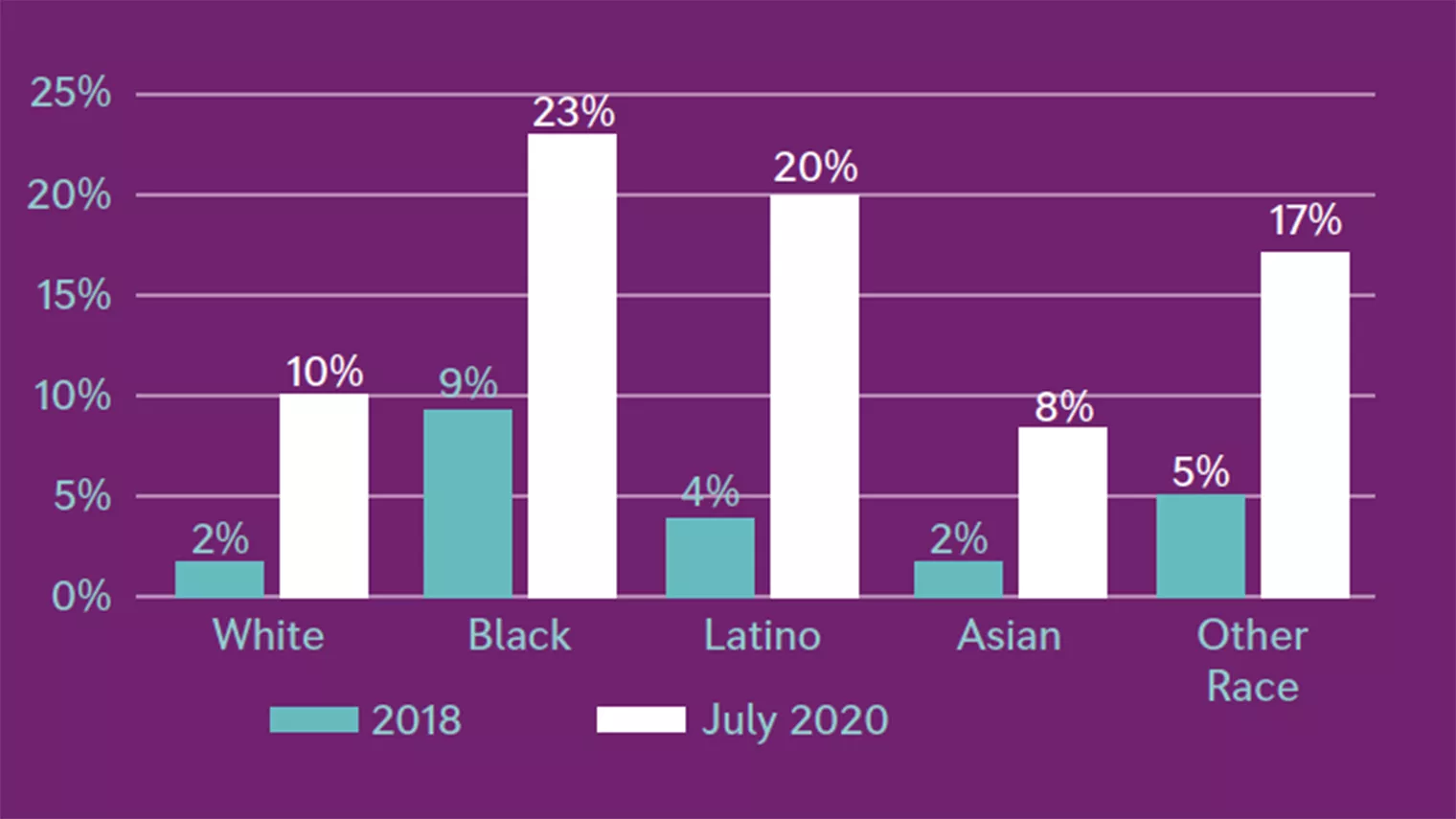

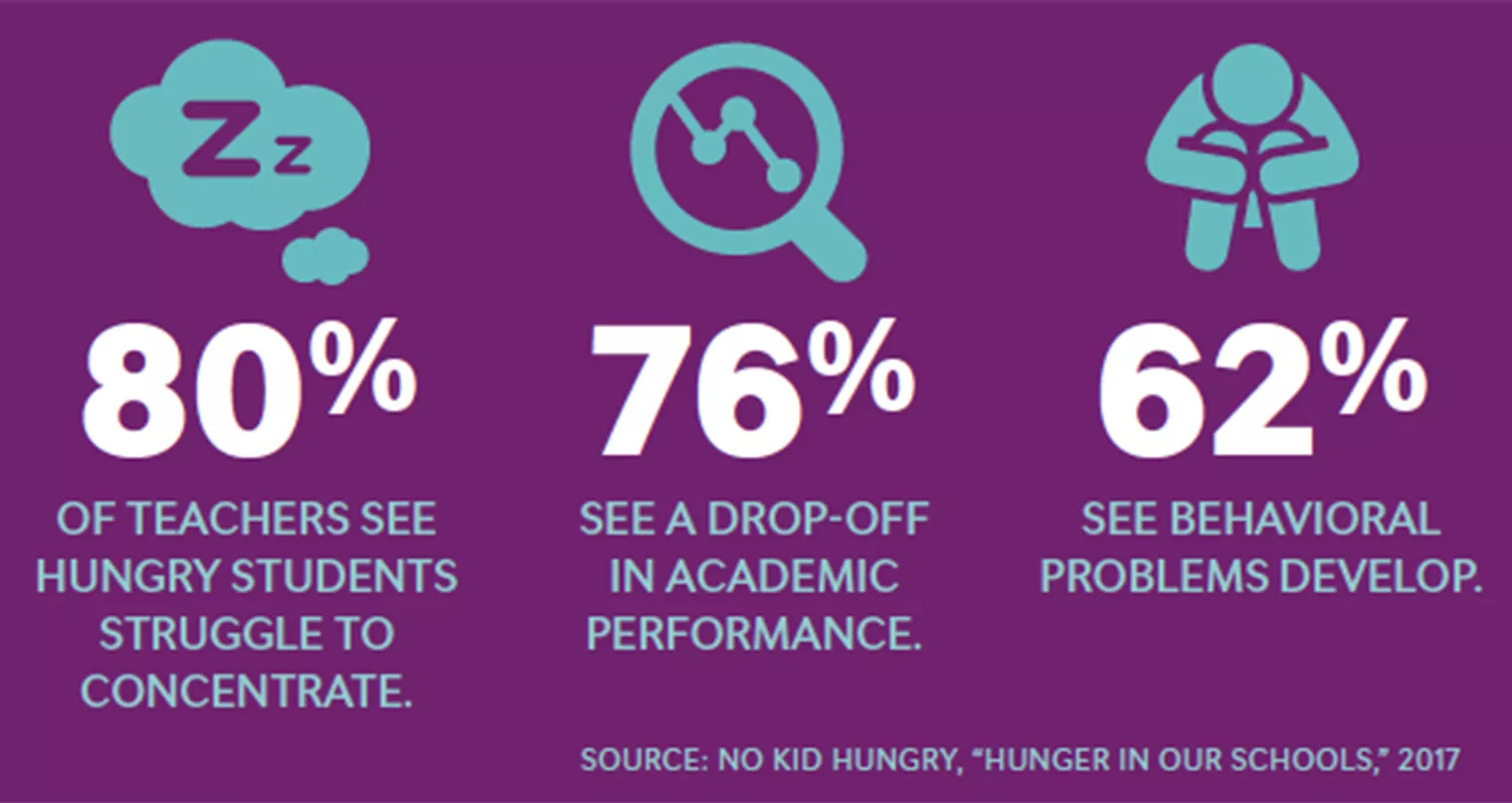

Hunger is a public health issue that has terrible effects on students’ academic and social growth. It disproportionately affects Black, brown, and Native People, as well as rural and immigrant families.

The nation has long relied on public schools to help ensure that all children have access to healthy meals. In the 2019 – 2020 school year, K–12 public schools served 29.6 million lunches and 14.77 million breakfasts per day. Nearly three-quarters of those meals were free or reduced-price.

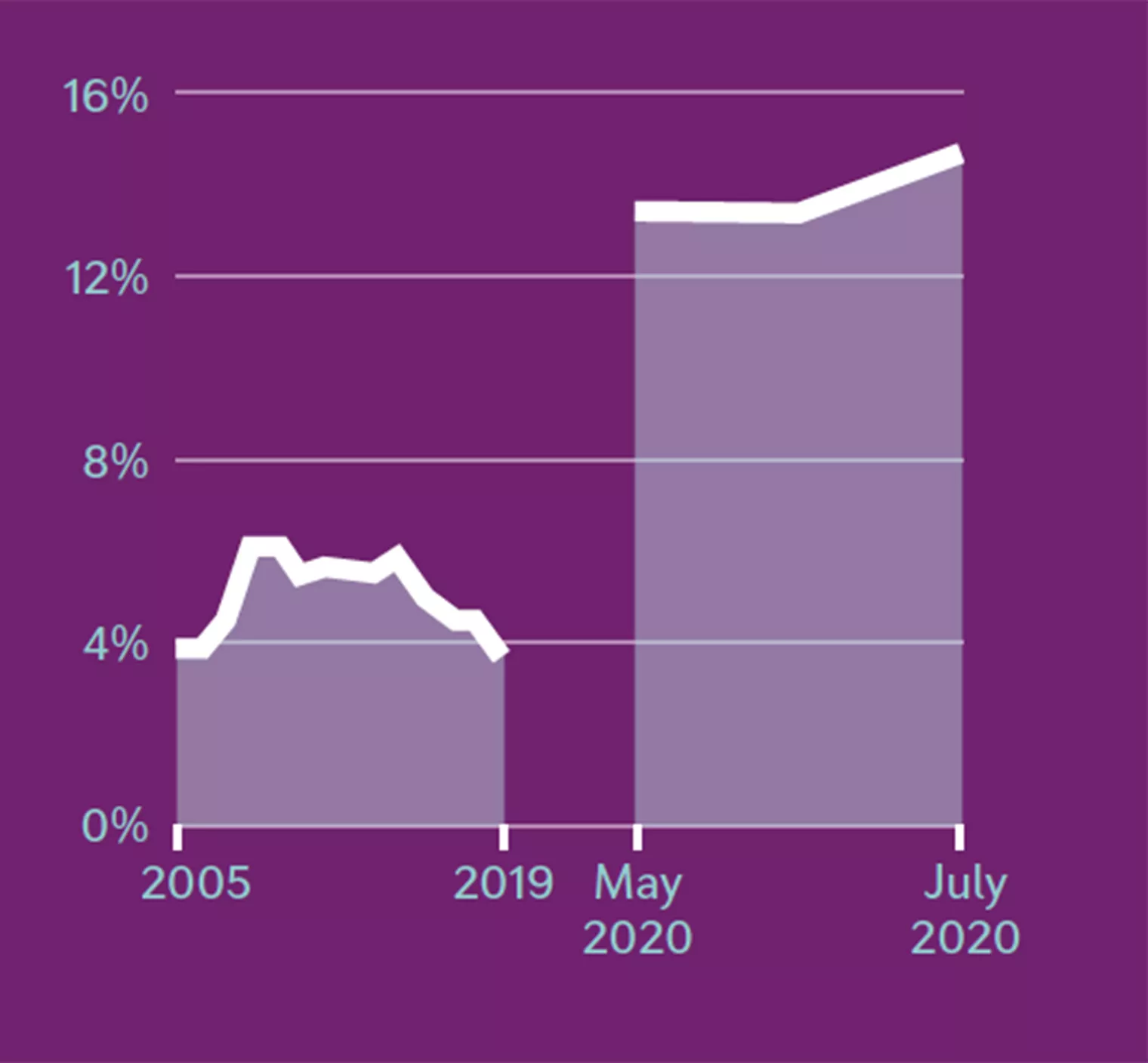

Now, record job losses and economic turmoil wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic are making America’s hunger crisis far worse than it has been in decades, as evidenced by a September 2020 report by the Food Research & Action Center. And with many students learning remotely or in hybrid situations, it has become harder for schools to get meals to some of the students who need them most.

Educators have led the charge to keep students fed. They have made their voices heard on Capitol Hill and have taken heroic steps to feed kids in their hometowns.

Rita Morales has worked in school food service for 15 years in Las Cruces, N.M., where nearly half of children live in poverty. There, the need for school meals is so great, the district has two shifts of workers operating 14 hours a day.

Morales oversees 12 employees on the 2 to 8:30 p.m. shift: “Three bagging the breakfasts, three bagging lunches, three bagging vegetables and fruits, and three wrapping the hot main entrée,” she says.

Morales says she feels honored to be in a position to help.

“I’m so proud to be part of the Las Cruces response to this crisis,” she says. “I love my job, and I work for my kiddos.”

It has taken ongoing advocacy by NEA and hundreds of other child advocacy and social justice organizations to pressure the U.S. Department of Agriculture—which oversees the National School Lunch and School Breakfast programs—to do the right thing. So far, the agency has continued to provide adequate funding and allowed schools the flexibility to serve students off-site.

Hunger and the Pandemic

Be Like Dori: Get the job done

Doriann “Dori” Wiegand is a food service leader at Knapp Elementary School in Michigan City, Indiana.

NEA Today: How did your job change once the pandemic hit?

Dori Wiegand: After schools shut down on March 13, we had to move fast to come up with how we would keep kids fed until June, when our summer program begins. I helped out at my school and another school in our district. We made thousands of meals, and families came and picked them up. Also, our school bus drivers went to playgrounds and trailer parks to distribute the prepared food.

What has been the most difficult part of school buildings being closed?

DW: There are times the work has been exhausting. But really, I just miss the kids coming into the lunchroom and getting those smiles and hugs.

Your food service program has reached nearly the same number of students while buildings are closed as it did before the pandemic. What strategies worked best?

DW: We pack breakfasts and lunches for five days and freeze the packages. Then we distribute the packages during two pickup times on Mondays so the adults don’t have to return multiple times per week. Each bag has instructions on how to thaw or heat the meals, which were everything from sandwiches to orange chicken to tacos. We include a lot of fresh fruit and vegetables, too, plus cartons of milk.

People are supposed to place their orders online by Wednesday for the following Monday, but even if they aren’t registered, we don’t turn anyone away.

What lessons from the pandemic will you carry with you in the future?

DW: Our entire staff worked so well together to get the job done. We did more than I ever thought we could. We had to for the kids—three-quarters of them are from low-income families. We figured out everything we had to do at unfamiliar job sites to get through those first critical months, when suddenly all of our students were learning virtually. Our district provided the masks and gloves and disinfectants we needed. The food service director made it a priority to keep everyone employed.

We will all just be so happy to see our students at school again and to be able to see each other at union meetings.

TAKE ACTION

You can help NEA advocate on child nutrition and other critical issues. Find out how at nea.org/advocating-for-change.