Dr. Stephanie Serriere began formulating her concept of “carpet time democracy” as an elementary school teacher. She observed that her young students had a natural interest in issues of fairness and equity as they entered the classroom—for many, the first civic space of their lives.

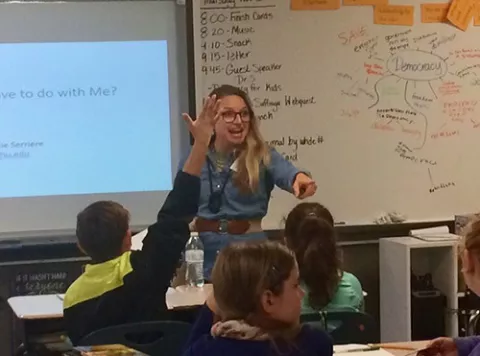

Those experiences drove her research in early civics education. Now an assistant professor of social studies education at Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus, Serriere prepares future teachers to “purposefully teach democracy.”

“As I tell my undergraduate students and pre-service teachers, democracy is not something we are just gifted,” said Serriere. “Democracy does not live happily under plexiglass in Washington D.C., protecting our rights and freedoms. No! We must actively work to maintain it.”

Here are highlights from our conversation with Serriere on why civics instruction should start early, and how to go about it.

Why is it important to get elementary school students interested in civics?

As children enter school, their concept of community broadens considerably. As educators, we can shift the lens of the curriculum to be about their classroom, their school and their wider community, and their concerns and observations. That kind of civic learning will be relevant to even the youngest students.

Eventually, they will find things they want to change.

During my research, I followed a group of 5th grade girls who wanted to change their school salad because it had bacon and cheese placed on it every day, and they thought it was unfair. They said to their teacher: “This isn’t right! This doesn’t include all of us.” They pointed out that some students are Muslim, some are lactose intolerant.

The teacher said, “You know what? You’re right!” and guided them through a process of inquiry. They conducted opinion polls in the school, researched USDA requirements for school lunches, and proposed new options to cafeteria personnel. And they succeeded.

Fostering perspective taking, which is at the heart of many of these projects, has been shown by research to be the springboard of a lifetime of empathy. That’s why we cannot wait until our students are older.

How did you first get interested in early civic learning? What worked best with your students?

When I was an elementary school teacher, I noticed that boys were particularly concerned about being a “real boy” and not being “girly.” I wanted to challenge some of those traditional gender norms, so I read them children’s books like Oliver Button is a Sissy, and Fernando the Bull to promote the idea that boys can be any way they want to be. But that wasn’t as compelling as the ideas students came up with on their own.

So I opened up conversations about equity and asked students what they noticed. I started using photos to document their play episodes, the playground, the classroom, and their social interactions, and asked them to imagine what would happen if “x” changed.

For example, I’d say: “So you told her she had to be silent because she’s pretending to be Tinkerbell, who is silent in the movie. But you have the power to change that. What if Tinkerbell could talk?”

I would use photos and their own classroom and playground scenarios to reimagine our social reality. Students always benefit from knowing that they have the agency to shape their lives and their community.

How can educators figure out what their students are prepared to discuss and understand?

Educators should keep asking students, “what do you see that’s not fair?” and keep teaching them about historical injustices as well. We should shine a light on the citizens who have made a difference, in the past and the present.

Of course students need to have an understanding and awareness of public and community issues. They need to have the ability to obtain information, think critically, and enter dialogue with others with diverse perspectives. There are news websites like “CNN 10” that boils down the national news for kids. Educators can show how national issues play out in our local settings too, using local news sources.

We also need to ask young people to think critically, and ask, “Whose perspective is heard here? Is this valid?”

It is so vital to teach students how to evaluate the vast amount of information coming at them on the internet alone, and the perspective from which it’s written. Only then can they create their own informed opinions.

What is your advice to teachers who want to discuss big issues without divisiveness?

One way is to adopt a mindset of inquiry with students. That means moving away from having “right or wrong” answers, and instead playing with ideas, unpacking questions, and resting in the not knowing.

Teachers can help students try out different perspectives by giving each a role, like business owner or environmentalist, in a town hall forum. That makes the conversation less personally charged.

I once wrote about children discussing the book Hey Little Ant. In the book, a boy is considering whether he should step on the ant in front of him. After all, ants are just thieves at picnics. But those kindergarteners cut through that plot line so quickly, and we were on to questions like: Is he a criminal? If he steals, should he be killed? It was amazing how quickly the conversation flipped to a higher plane.

Kids are too often told the answer and we need to work on getting them to think about issues, growing their ability to wade through differences of opinion and evaluate arguments.

What can educators do to emphasize the importance of civic engagement and social justice to their students?

It’s imperative to give students plenty of examples of how others have effected change. Introduce them to civic systems, whether that is helping them contact a local official, helping them contact cafeteria personnel, or writing to the president. We can infuse the elementary curriculum with civics, using students’ own interests and experiences as their motivation to read and write.

Young people, especially young people of color, have political knowledge and expertise that must be acknowledged, respected, and examined in our classrooms. Youth of color have particular knowledge about unequal implementation of democracy that white youth may not have or recognize. All young people do not have equal access to power, but our classrooms can be places where our students have more equitable opportunities to notice inequities and take action on them.

Even when a civic action project does not end in a visible victory, we can ask: “What can we learn from this?” Our research shows it’s best if students have multiple chances throughout their schooling to take on personally relevant civic action projects.

Dr. Serriere’s suggested resources for educators

• SOCIAL STUDIES AND THE YOUNG LEARNER: This is the National Council for the Social Studies’ (NCSS) premier elementary practitioner publication that blends practical teaching inspirations with theory, Social Studies & the Young Learner.

• ZINN EDUCATION PROJECT is a non-for-profit supported by ReThinking Schools and Teaching for Change. Their teaching resources and seeks to introduce “students to a more accurate, complex, and engaging understanding of history than is found in traditional textbooks and curricula.”

• TEACHING TOLERANCE aims “to help teachers and schools educate children and youth to be active participants in a diverse democracy.” They provide classroom resources, professional development, and a regular publication.

• NATIONAL ARCHIVES RESOURCES FOR TEACHERS: Explore and analyze primary sources from U.S. history and other resources.

• LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RESOURCES FOR TEACHERS: This in-depth collection of classroom materials and digital and historical primary resources can be used across subjects.

• KIDCITIZEN, a project of the Library of Congress, allows kids to explore Congress and civic engagement through primary source documents.

• THE FREECHILD INSTITUTE works to promote the idea that the knowledge, action, and wisdom of children and youth can make the world more democratic.

• WHAT KIDS CAN DO is a nonprofit that promotes youth as valuable resources and engages them as knowledge creators.