When governors and state superintendents started to close schools in early March because of the coronavirus, more than 30 million public school students (and families) were left wondering, “Now what?” Educators answered by either ramping up existing resources or thinking creatively about lesson plans and online resources. At the same time, school districts across the country went into rapid-response mode and executed learning continuity plans for students, with varying degrees of success.

How well these plans worked depended on several factors, according to Fernando M. Reimers, director of the International Education Policy Program at Harvard University.

In a blog post for Educational International—a federation of 32 million union educators around the world—Reimers wrote that distance-learning plans “will most likely work well for children whose parents have more education, who have other social advantages, and who have access to resources, including online connectivity and devices, so they can con- tinue to enjoy structured opportunities to learn. For many children lacking those conditions, the period of physical distancing is likely to result in very limited opportunities to learn.”

Smoother transitions for high-tech schools

Cecily Corcoran, a middle school art teacher from Arlington Public Schools in Virginia, was grateful to be ahead of the online learning game. She had made it her personal goal earlier in the school year to update her materials and place them online in case students missed a lesson. Once her school closed, she went into overdrive and created 60 video tutorials, each under 10 minutes long.

“My motivation was to get students into another world of focus and concentration, to be proud of what they’re doing, and still learn and have fun in the midst of something we can’t comprehend,” says Corcoran.

Even on short notice, many educators were able to quickly adjust.

In a matter of hours, Antonio Moses, a fifth-grade teacher at Griffith Elementary School in Winston-Salem, N.C., worked with colleagues to ensure students had access to the programs and tools they needed to stay on track.

“We shared resources amongst grade levels that would help our students learn at home,” Moses says. Fortunately, his students were equipped with laptops and Wi-Fi.

“Many of my students were submitting work and continued to work on projects we had started in class,” he says.

“I was surprised they were getting the work done, submitting it to me electronically without any problems, and … reaching out to me if they had any questions.”

“Perhaps now society will begin to truly value public education, how challenging the profession of teaching is, how teaching goes beyond academics, and educators … finally receive the respect, support, pay and funding needed to do the job effectively.”

-TOM DERIS, THIRD-GRADE TEACHER, MINNESOTA

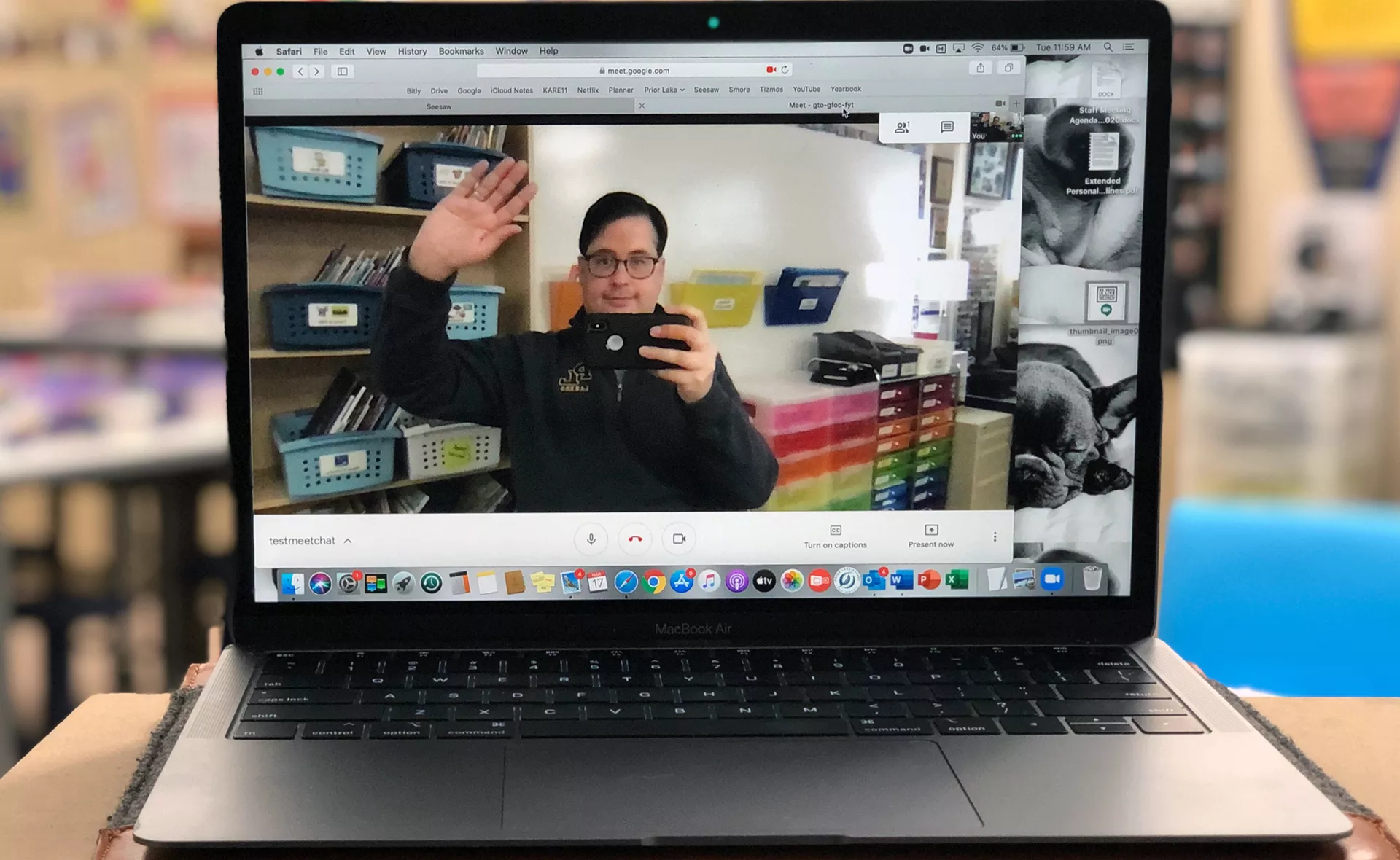

Minnesota’s Beth Leighton, a technology integration specialist for Prior Lake-Savage Area Schools (PLSAS), says, “Lucky for us, we already had a framework in place that teachers are familiar with and use often.” PLSAS educators use Google Sites, which lets teachers across the district collaborate and share resources. Educators have used the site increasingly over the last few years, but it’s really taken off since the pandemic.

Lessons learned

This ability to share work has also benefited educators such as Tom Deris, a third-grade teacher in PLSAS. “We don’t have to reinvent the wheel,” he says, “because the goal right now is to work smarter, not harder.”

After initially sending students home with a handful of worksheets, links, and resources to use at home, Deris successfully—with the help of Leighton—moved his core subjects online to the platform Seesaw, where students could easily upload the work Deris assigned each morning.

“Most assignments are on Seesaw, and parents have expressed they like having all the work in one central location,” Deris explains. “The kids can get on their devices, go directly to … assignments, and follow the instructions step-by-step.”

He can post videos, banter the way he would normally do in class, discuss the homework for the day, and go over expectations and how best to reach him. Funding for support and technology have contributed to the success of the district’s online learning plan.

Challenges for low-income communities

When schools closed in Alabama, “I felt very unprepared,” says Dashannikia Holston, Ed.D., a sixth-grade teacher in the Fairfield City School District. “I teach students who are in a low-socioeconomic status, and the resources we have to aid our children in times like these are very scarce.”

Most of the students in Holston’s district lack internet access in their homes.

Last year, the Associated Press analyzed census data and found that nearly 3 million (18 percent) of U.S. students lack home internet access, and 17 percent had no home computers. Corey Williams, a federal lobbyist for the NEA, thinks that number is actually much higher.

“The statistics vary widely about how many kids … go home and don’t have access to the internet. In some instances, we’ve calculated approximately 12 million, but it’s really difficult to know exact numbers,” Williams explains. “What we do know is that [internet access] was already inequitable and unfair to many children when school was in session,” especially those in low-income and rural areas.

Creative solutions

The coronavirus has made inequities worse, but that didn’t stop Holston and her colleagues from giving students and their families needed support.

While district officials worked with local internet service providers to extend free Wi-Fi coverage, “we worked with many of our parents and community stakeholders to make sure students were included in this coverage,” she says.

Next, they needed to address the insufficient number of devices for every student. Survey results allowed district officials to determine the number of families who were without a device, as well as how many families with multiple children within the school system could share one.

“Although we could not provide each individual child in the district with a device, we wanted to make sure that the families who had no resources were equipped with at least something to use,” she says.

Students have responded well to online learning, too, and have shown an eagerness to participate, Holston says.

Online learning still isn’t enough

Some students with individualized education programs or 504 plans— which accommodate students who can learn within a general education environment with modifications—have unique challenges.

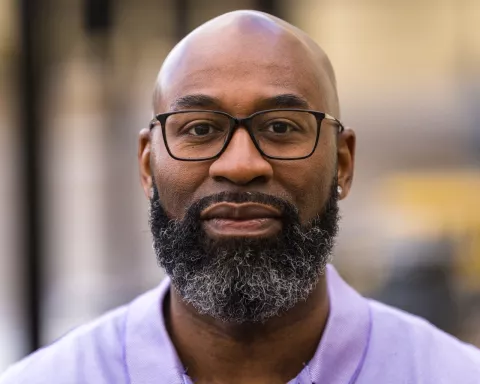

This is where equity issues get tricky, says Arizona’s Kareem Neal, a special education teacher at Maryvale High School in Phoenix and the 2019 state teacher of the year.

When school officials switched to online learning, “they trained us as if it would all be the same, but there may be differences with special education students, particularly for classrooms like mine,” says Neal, who teaches students with mild intellectual disabilities in a self-contained classroom.

While most teachers could engage dozens of students online, “my students wouldn’t be able to learn that way. … I needed the one on one.”

So his school found a way. A paraprofessional was assigned to Neal, and remotely they worked together through Microsoft Teams to connect with individual students and their parents. This way, students were getting double the lessons during the week and the one-on-one attention they needed.

Public education after COVID-19

The full impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the future of the public school system remains to be seen. What has been on full display is the inequities that plague schools across the country and the commitment of educators to support their students.

“The health and safety of the entire community is the top priority always,” says David Edwards, general secretary of Education International. “But I hope we are learning the value of investing in a strong public sector, including educa- tion. Our job as educators and unionists is to make sure that the adjustments needed now and into the future follow the fundamental principles of a quality public education for every student.”

Find out how NEA is working to secure federal funding to help schools face the COVID-19 pandemic and how you can take action. Go to EdVotes.org/COVID.

What These Educators Think About the Future and What They Hope the Nation Will Learn

Cecily Corcoran

Dashannika Holston