Entering middle school as the new kid is hard, but for Auggie Pullman, the main character in the best-selling middle grade novel Wonder by R.J. Palacio, it’s downright terrifying. Auggie has Treacher Collins syndrome, a rare craniofacial disorder that causes major malformations of the face.

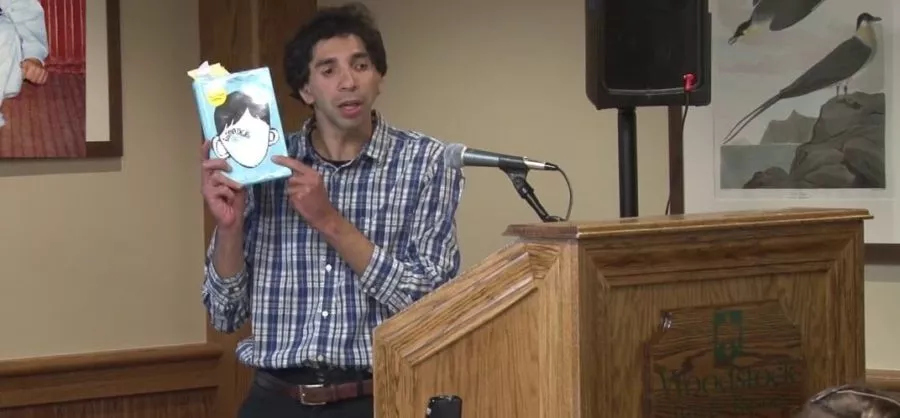

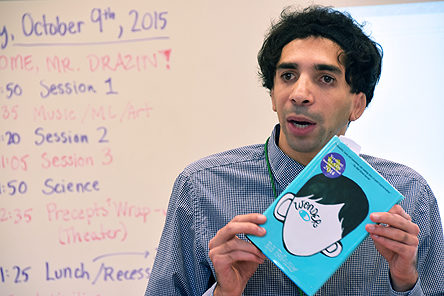

Vermont educator and NEA member Sam Drazin was born with the same disorder and had to have seven surgeries on his face while he was in school.

He was struck by the similarities between his and Auggie’s experiences. "It was like I was reading about my own childhood," he says. But it was the book’s message of acceptance and kindness that prompted Drazin to create a presentation for his school to raise awareness about disabilities and create a culture of acceptance.

The presentation, “Bringing Wonder to Life,” was so popular he was soon asked to speak at more than 30 schools throughout New England. In 2014, he founded the nonprofit Changing Perspectives to provide disability awareness programming to schools nationwide.

NEA Today sat down with Drazin to talk about his curriculum and messages of inclusion and acceptance.

How did you decide to broaden your presentation into an entire curriculum?

Sam Drazin: I realized that “one and done” wasn’t enough. My school had developed a disability awareness day where we had simulation stations so students could experience what it’s like to have different disabilities. We had a lot of community involvement and a variety of guest speakers and our students were really engaged around the concept of disability – what it is and what it means. Between my presenting about the book Wonder and the one-day awareness event, there was a huge amount of positive feedback and a real desire from teachers to have more resources about the issue.

When we encounter others with disabilities, we tell kids not to stare. Is there a better message to convey?

SD: One of the reasons this work is so important is that we are trying to be a seed for social change and have a ripple effect. Our society has a “shush, shush, don’t talk about it” approach, but intolerance is the result of ignorance. We need to shift our thinking and mentality. We need to acknowledge that kids are curious and to move beyond our own discomfort and vulnerability.

If you’re in the grocery store and your child is looking, it’s OK to not say anything in that moment, but when you get in the car you could say, “Hey did you notice that man in the wheelchair” or whatever the difference was. If the child says it was weird or scary, don’t try to change their language, just affirm that what you saw was different and unexpected. Start the conversation.

However, one thing I talk to kids about is that it’s natural to stare – we are naturally curious – but people notice when you are staring at them even if you think they don’t. It’s much better to acknowledge people with a smile and a nod or a wave.

Can you explain how being ignored is as hurtful as being bullied?

SD: There is a lot of work right now around the issue of social isolation. Kids who feel invisible, who fly under the radar, are often suffering silently. Sometimes the quietest kids are those who are crying out for help the most. Isolation can pull you down into yourself so far that it’s very hard to pull out. You can withdraw from everyone and everything and it can become a pattern for life.

When I was in high school and feeling isolated, I fortunately started babysitting. I’d go all day with nobody talking to me but when I walked into the door of those kids’ houses, they’d run and tackle me they were so excited to see me. They didn’t care what I looked like. I realized then that young kids are naturally accepting. All kids see differences, but it’s not until maybe fourth to seventh grade that they start to react. It’s a pivotal time. We need to start raising awareness about acceptance of differences when kids are younger.

Sam Drazin

Sam Drazin

Why are kids with disabilities ignored? How can we change that?

SD: When we think about our educational model, too often special education students come into classrooms for a short while and then they are whisked out of class. They automatically feel ashamed for their differences and students don’t have a space to talk about them. We need to become more comfortable with differences. We need to feel safe asking questions and move away from a “look away” culture.

Once teachers open doorways to conversations about disabilities, kids want to ask questions and they want to share. Students with disabilities gain confidence and self-advocacy skills when they are in a classroom where the teacher says let’s talk about it. It becomes cool to be different. Everyone begins to share what makes them different and lifts the pressure to just fit in. The conversations are so rich. You see how hungry students are for information. They want to learn. Intolerance is the result of ignorance, so we need to open up and have those conversations.

What are invisible differences kids have that they are afraid won’t be accepted?

SD: Social and emotional disabilities or effects of trauma are differences you can’t see and are harder for peers to empathize with. It’s easier to be naturally empathetic for a classmate who has to use a wheelchair than for the classmate who has explosive behavior as the result of trauma or might behave differently because they are on the autism spectrum. Again, talking about it raises awareness and increases tolerance and understanding.

Why has the book Wonder and a curriculum about disability and differences awareness resonated with so many educators?

SD: In our current situation in our country and around the world, people are becoming more attuned to the value of empathy and kindness. In the 21st century where information is instantly available, what skills do you need? You need to communicate with others, collaborate with others, network. Not just with the person who lives next door to you or in your town, but with someone who could be across the country or from across the world. Now more than ever before we see the value of choosing kindness and how easily our systems fall out of place when we don’t.

_____________________________________________________________________

If you loved Wonder by R.J. Palacio, here are more middle grade titles featuring children facing personal challenges or struggling with their identity:

Fish in a Tree by Lynda Mullaly Hunt (Nancy Paulsen Books, 2015)

Sixth grader Ally is good at math and a creative artist, but thinks poorly of herself because she has trouble with reading. Ally’s new teacher helps her understand that everybody is smart in different ways.

Restart by Gordon Korman (Scholastic, 2017)

Chase Ambrose doesn’t know who he is. The eighth-grade football captain fell off a roof and the resulting head injury erased his memory. Back at school, he comes to realize that he was a bully who’d done a lot of harm. Chase has a chance to start again, but others must also accept that he has changed.

The War that Saved My Life by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley (Puffin Books, 2016)

Thanks to her club foot and abusive mother, Ada’s entire world is her one-room London apartment. When her younger brother is evacuated to the countryside during World War II, Ada sneaks away with him and learns how to move her life forward.

Books recommended by reading and literacy specialist Rachael Walker.