Key Takeaways

- College administrators have been cutting budgets, furloughing and laying off thousands of staff and faculty, and closing academic programs. But at what cost?

- Budget cuts mean larger classes, fewer advisors and decreased support for students. This means students can't get what they need. This isn't what public higher education is supposed to look like.

- Massachusetts union members are fighting back, and they're winning. State lawmakers agreed to no further cuts this year. They can choose to invest more in public higher education, union members say.

Massachusetts university and college administrators have spent the past six months or longer talking about budget shortfalls, planning and executing thousands of layoffs and furloughs, and cutting programs that are essential to student learning.

They call it a time of austerity, and point to the pandemic as their reason.

Meanwhile, unionized faculty and staff are fighting for investments in public higher education, so that any Massachusetts student—white, Black, Latino, Native or newcomer—who wants an excellent, affordable higher education to fuel their dreams and help them become the state’s next entrepreneurs and innovators can get it.

“Campus executives — I’m not calling them leaders anymore — are not going to defend our public mission,” says Massachusetts Teachers Association (MTA) Vice President Max Page, a professor at UMass Amherst.

But, working with students, union members are.

With drive-by protests by day and light-up messages shining into the night, staff and students spent much of 2020 delivering a message of investment—and they’re being heard. In December, after union members sent thousands of letters to lawmakers, the state House and Senate passed a budget with zero cuts for public higher education. At one community college, trustees are reconsidering a decision to eliminate multiple, career-oriented programs. At a state university, administrators withdrew a proposal for faculty furloughs.

Now, as 2021 commences, faculty, staff and students are leaning on lawmakers to override a veto of the budget by Governor Charlie Baker. They’re demanding UMass administrators, in particular, rehire the more than 1,000 employees that were laid off or furloughed this fall across the five UMass campuses. At state universities and community colleges, too, faculty and staff also are leaning on presidents, chancellors and trustees to stop the cuts and focus instead on increasing opportunities for students.

With the help of NEA, union members have been pouring over campus budgets[TJ[1] and financial reports and finding money that can be used to support learning—like the many millions of dollars that UMass administrators have deemed superfluous and transferred to the university’s foundation for aggressive investing.

“I can see with a lot of certainty that in UMass, the austerity budget is complete bullshit,” says Anneta Argyres, president of the Professional Staff Union at UMass Boston.

The bottom line is this: Faculty and staff want every student to get what they need to succeed. But budget cuts mean bigger class sizes, less time with dedicated faculty and staff advisors, and more obstacles for students to face alone.

“What are these campuses for, if not teaching and learning? Without that, why do we even exist?” asks Fitchburg State University professor Aruna Krishnamurthy, who helped convince Fitchburg administrators to abandon a plan for furloughs this fall.

How We Got Here

After a couple of decades at Salem State University, one of the Commonwealth’s nine state universities, Rich Levy has become more than a teacher of political science. He’s also an advanced student in the field of public higher education—how the system works and how it doesn’t.

Over the past 20 years alone, Massachusetts state spending on public higher education has decreased by 32 percent per student. Over the past 40 years, points out Levy, it’s fallen by 50 percent. “According to most readings, it’ll be zero by 2057 if nothing changes,” he says.

As state lawmakers have turned their backs, institutions have asked students to make up the difference. Since 2001, average tuition and fees at the state’s four-year public colleges have more than doubled. At Salem State specifically, tuition and fees have gone up $10,000 since 2001, says Levy.

Only students from the wealthiest families can afford to pay these prices; working-class students and families must borrow. Consequently, from 2004 to 2016, the average debt per graduate from a Massachusetts four-year public college grew by 77 percent, outpacing all but one other state. (It’s you, Delaware.)

State funding cuts also have changed the way that administrators think about their work, says Krishnamurthy. It’s all about the money. “Because the state doesn’t fund adequately, campus leadership thinks about the institution in terms of profits, rather than focusing on academics,” she says. “It’s like they’re thinking ‘we have to run [our college] like a business before it collapses,’ and the priorities are getting skewed.”

Lately, the pandemic has worsened the revenue gap on some campuses, especially those that rely on dormitory, cafeteria or parking fees for operating funds. But the money issue isn’t new: the problem took root decades ago when politicians first ignored their responsibility to public colleges and universities, and big banks and corporations stepped in to create a profitable (for them) student-lending industry.

These bigger issues can’t be solved through more cuts, says Levy.

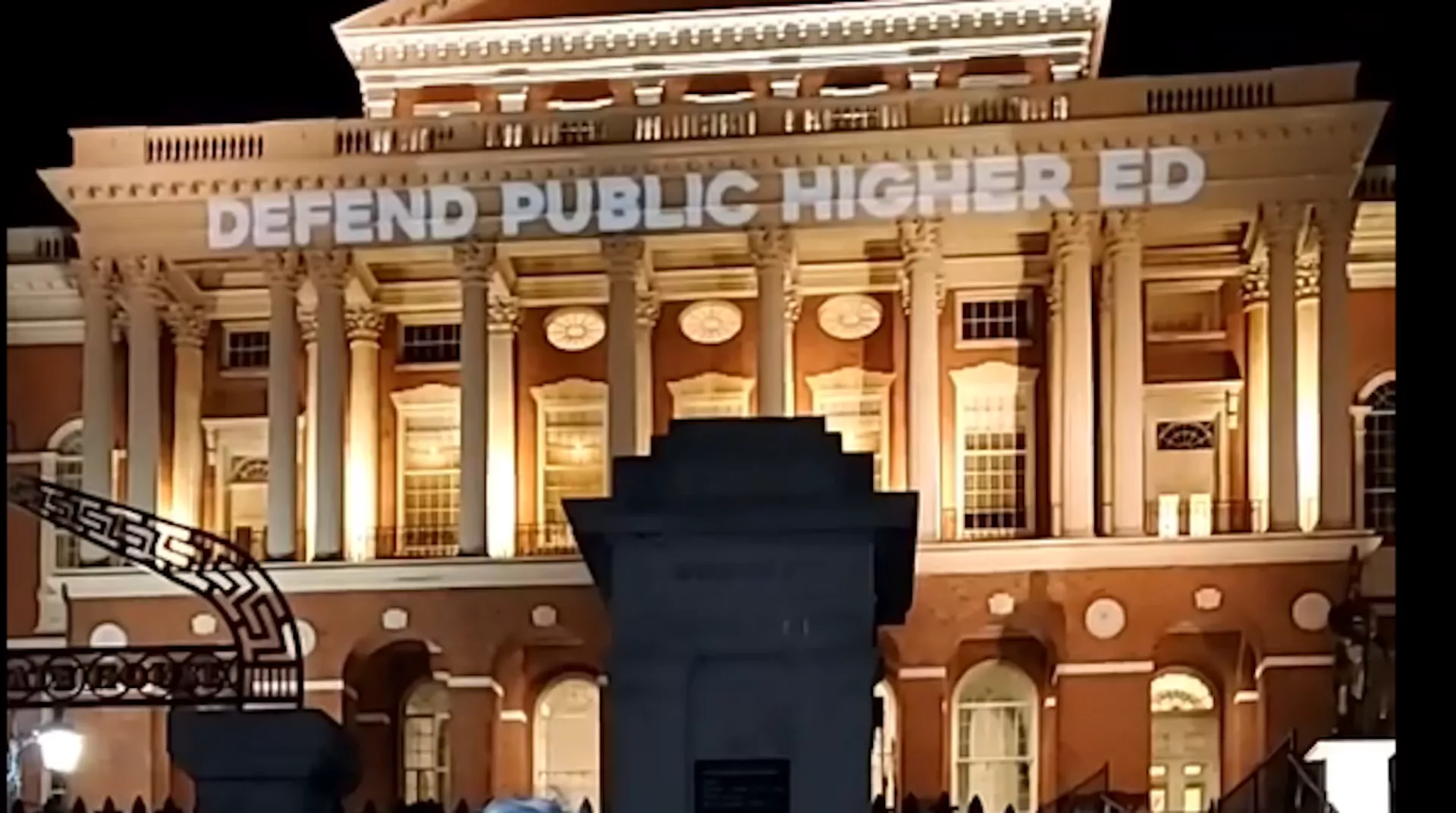

Light Up the Night

In late November, as the longest nights of the year approached, Massachusetts faculty, staff and students “lit up” campuses across the state with glowing messages, cast onto campus buildings and also the Massachusetts State House in Boston.

“Defend public education,” they said.

“Fund our future.”

At Salem State, like many other places, administrators are attempting to cut their way out of their budget hole, forcing employees to take three weeks of unpaid furloughs, which they say will save $8.5 million. In response, in November, the MTA-affiliated faculty and librarian union filed a charge of unfair labor practices with the state labor board.

The budget gap at Salem State shouldn’t be balanced on the backs of faculty, who have been working tirelessly to re-invent their classes online and support struggling students, says Levy. Nor should it be dumped on students who are already working two to three jobs.

Union members know that many “students are food insecure and functionally homeless… working two jobs, taking care of family members, and going to school full-time,” said Salem State librarian Cathy Fahey. On the other hand, “the president’s office and Board of Trustees is very detached from what our students face.”

Salem State’s administrators borrowed hundreds of millions of dollars to construct new dorms, dining and fitness facilities, points out Levy. They’ve already tried to pass the costs to students—last year, full-time undergrad students each paid $3,300 toward the university’s debt service. Almost 25 percent of what students pay to the university goes toward its capital debts. (Read more about how Salem State’s students are paying for the college’s capital debts.)

Now, Salem State’s faculty and librarian furloughs, which will take place during the January break, spring break, and the last week of May, will further injure students.

“These furloughs have been presented as if faculty play tiddlywinks during those weeks,” said Levy. “What students and faculty are saying is no — in January, you’re finishing your syllabus, reaching out to students, doing advising work. During spring break, you’re correcting student work, giving feedback on papers, responding to student emails, preparing for the next couple of weeks. And, in May, there are department retreats, the figuring out what to do next year. It’s all presented as if this won’t affect students’ education, but students are smarter than that.”

Cutting to the Bone

Union members believe every Massachusetts student who wants a higher education should be able to get one—and it should be an excellent one. But budget cuts are making it harder and harder for students to get what they need.

“Institutions are struggling with budgetary concerns — and I think that’s real. But we need to think long and hard about how money is spent, and how budgets are cut,” urges Stephanie Marcotte, a student advisor at Holyoke Community College, one of three Hispanic-serving community colleges in the state.

“If we cut services, are we going to impact graduation and retention rates?”

Public colleges and universities are supposed to be accessible to all students, whether they’re Black, brown, and white. But when budgets are cut—and tuition is raised and support programs are cut—access is denied. Only the rich can thrive. “Public higher education is a primary gateway for racial and social justice,” says Michelle Corbin, a sociology professor at Worcester State University. “When we cut that budget, when we let it wither, when we don’t support it…we further marginalize the most vulnerable students who are trying to access what we call the American Dream.”

I’s not just about graduates getting better jobs. It’s that, and also about how a higher education can help liberate oppressed people and communities—black, brown, women, working-class, and LGBTQ—and it’s never been important, she adds.

And it’s also not just about faculty. In fact, budget cuts disproportionately affect professional staff and other support employees. In 2020, a Washington Post analysis of federal labor data showed higher education’s support employees suffered the largest job losses last year.

“When there are cuts to budgets, the people who are the first to be let go are professional staff—coaches, advisors, tutors—the people on the ground, providing resources to students. When those pivotal people are gone, where does that leave students?” asks Marcotte.

The bottom line is this: Faculty and staff want every student to get what they need to succeed. But budget cuts mean bigger class sizes, less time with dedicated faculty and staff advisors, and more obstacles for students to face alone.

For first-generation students, or students attempting to balance college with work and family, this support is essential. “Advisers, writing centers—some get eliminated completely and some get shrunk, so students’ waiting time for help is longer,” says UMass Boston’s Argyres

At University of Massachusetts Amherst, two NEA-affiliated staff unions fought layoffs this fall, filing charges with state labor officials in September that called the layoffs illegal (and unnecessary). The university “is rushing to cut jobs when that is not necessary… we have offered multiple [alternative] ways in which our members are willing to sacrifice,” said Risa Silverman, co-chair of the Professional Staff Union-Amherst. After the union’s charges were filed, administrators backed off, and negotiated with the unions to implement unpaid furloughs instead.

Adjunct faculty also suffer disproportionately. At Salem State, nearly a quarter of adjunct or contingent faculty lost their jobs this year. At Fitchburg State, it was 30 percent. At UMass Lowell, 28 percent of adjuncts weren’t recalled in the fall.

Are These Cuts Really Necessary?

At Salem State, faculty members earlier in the year beat back a proposal to stop approvals of faculty tenure and promotion. The board had said it wouldn’t be “fiduciarily responsible” to approve promotions during the pandemic, when the state budget was unclear, Levy recalled.

But, Levy points out, “the total cost of tenure and promotion would have been one-tenth of 1 percent of the budget, and no level of state funding gets to that granular level.”

In this occasion, the pandemic looked like an excuse for doing something that administrators might want to do anyway—lessen the power of unionized faculty.

Meanwhile, at Fitchburg State, administrators suddenly announced faculty furloughs last fall, surprising union leaders. “We had to act and we had to act quickly,” recalls Krishnamurthy, who helped put together a committee involving three campus unions, which asked for information about student enrollment, reserved funds, etc. “We basically wanted to open the budget up for scrutiny. It seemed ridiculous to throw this word ‘furlough’ around without looking for other sources [of money], or even talking to us.”

Faced with the union’s questions, administrators withdrew the proposal. “My cynical sense is that it was just an attempt to take something from us,” says Krishnamurthy.

Another ill-fated administrative move that never made sense to faculty and staff: The sudden elimination by Springfield Technical and Community College (STCC)’s president of seven degree programs last June, including biotechnology and biomedical engineering, that have a 90 percent job-placement rate. In the fall, STCC trustees began the process of reinstating the programs, saying they didn’t understand the reasons for closing them.

“We do have money,” one trustee told the local newspaper. “If we have $14 million lying around, do we want to leverage some of that for at least one semester?”

Meanwhile, Quinsigamond Community College also announced in June that it was closing its innovative preschool, the Children’s School, and laying off its highly qualified educators. “We have tried countless times to tell the college that we are a top-rate school—the first Level 4 school in the state—and we could be a model for how to run this during the pandemic,” says lead teacher Brandi Dewar.

Meanwhile, other childcare centers are open, she points out. “They told us they can’t defend keeping us open because we’re not bringing in [money.] But we’re like, we’re not bringing in [money] because you closed us!”

And anyway, she adds, the children’s school isn’t just about profit. It’s about delivering a truly excellent, early education to the community’s children. It’s about equity. “It’s clear to us that they’re using the pandemic to say they don’t want to invest in this,” says Dewar sadly. “They’d rather put their money into a rainy-day fund.”

Meanwhile, UMass campuses have cut thousands of jobs this year, including nearly 1,000 at UMass Lowell alone. But the UMass foundation had a portfolio of $973.3 million in 2019—“more than enough to preserve staffing and programs,” point out MTA leaders.

Looking at Solutions

The state also has—or can get—the money it needs to make sure its public colleges are affordable to every Massachusetts family, and that the education offered by those institutions is truly excellent.

Massachusetts is one of the richest states in one of the richest countries in the world. And although the pandemic has put hundreds of thousands of Americans out of work, it hasn’t much hurt the nation’s billionaires.

Indeed, between March 18 and June 20, 2020, the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic, while 976,000 Massachusetts residents lost their jobs and countless others suffered a loss of income, the net worth of 19 Massachusetts billionaires increased by $17 billion, or more than 30 percent, a recent report found.

Think about how much a small, progressive tax on the state’s billionaires and its wealthiest corporations could help the state’s college students, and its public colleges and universities, union leaders say.

On Levy's campus, he has struggling students who can’t meet with him during faculty office hours because they’re working nights, working weekends, caring for their siblings or own children, trying to keep a roof over their heads, and hustling for food and transportation.

“Our students need a debt-free education. That’s what I’m pushing for and that’s what [my union] is pushing for,” he says.