Louise Smith, band director at Gautier Middle School in Mississippi, says the grief and loss from the pandemic feel similar to Hurricane Katrina, which devastated her region in 2005.

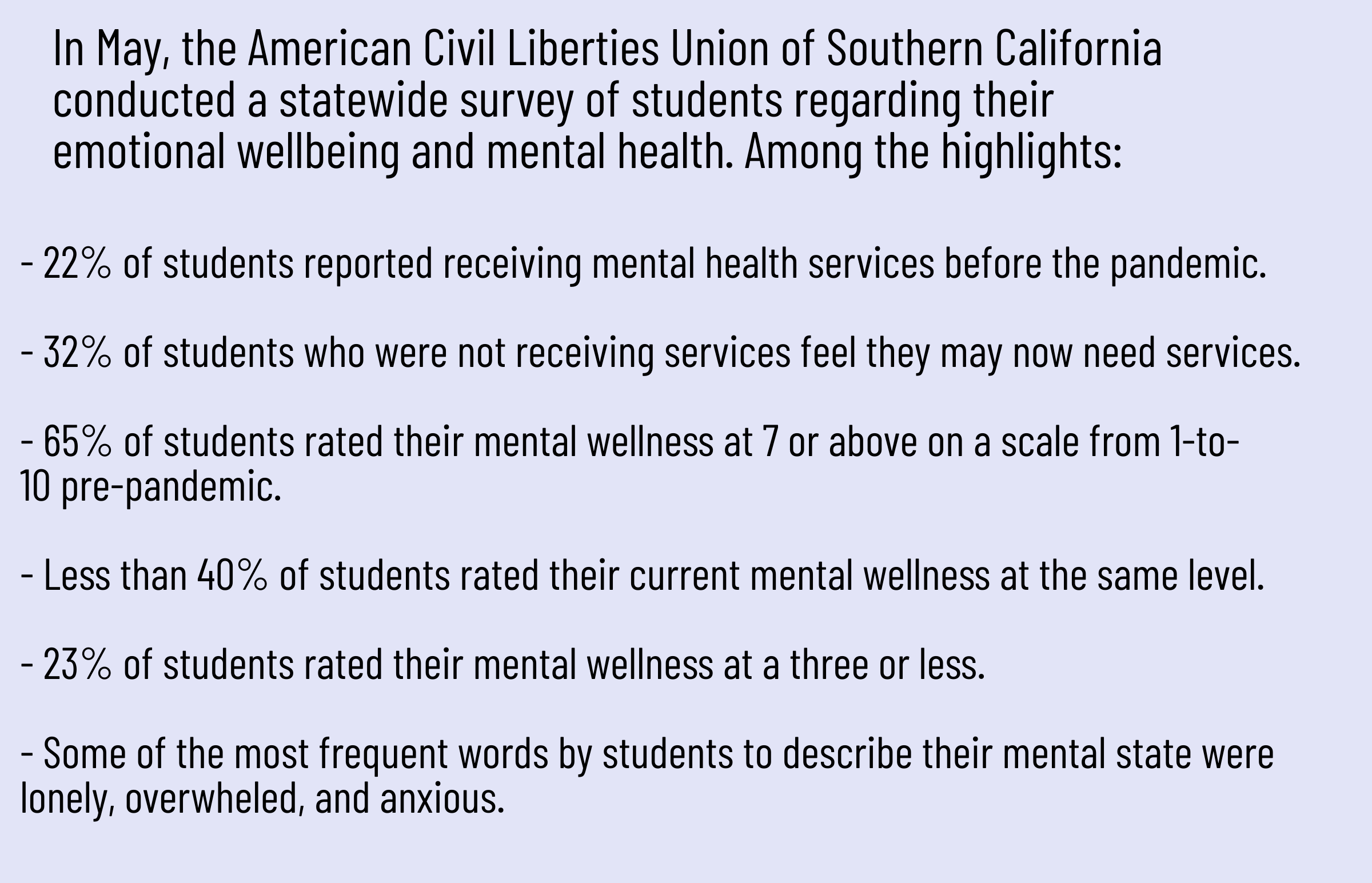

We're on the verge of a new school year, but “back to school” as we know it has been off the table for some time now. We still have more questions than answers. When will schools reopen? Should they reopen? If and when they do, how will students and educators be safe? What will instuction even look like? How will students, educators, and parents adjust to the “new normal”?

These questions are eerily familiar to Louise Smith, band director at Gautier Middle School in Jackson County, Mississippi. She remembers August 29, 2005, like it was yesterday. That was the day Hurricane Katrina slammed into Mississippi’s Gulf Coast, devastating her community. Smith, who was living with her mother at the time and was about to enter her third year of teaching, temporarily lost her home, and schools in her district were heavily damaged.

“It was devastating,” Smith recalls. “We were out of school for more than a month. My students had lost so much—their homes, [and] families couldn’t pay bills. Parents were trying to keep their kids safe.”

So when the coronavirus shut down schools this spring, many of her students felt the same fear and grief Smith remembers so vividly from after the storm. “The crisis is different, but the trauma is in many ways the same: The sense of loss and the emotional and economic hardships, the threat of illness, uncertainty about what the future is going to bring.”

No one wants students to safely return to classrooms more than parents and educators. The health and safety of students and staff, however, should be the primary driver behind the decision to reopen. Even if every safeguard and protocol is properly planned and executed, teaching and learning can’t just pick up where educators and students left off when the school doors closed some five months ago.

This isn't just about academics and “catching up.” School leaders must first rebuild safe spaces for students that will help them and educators navigate the trauma they’ve experienced.

Kathy Reamy, a school counselor in La Plata, Md., and chair of the NEA School Counselor Caucus, says that if distance learning continues into the fall - as appears likely in many states - anxiety and stress may be exacerbated, making it essential to implement stronger systems to meet the social and emotional needs of students and educators.

Kathy Reamy, a school counselor in La Plata, Md., and chair of the NEA School Counselor Caucus, says that if distance learning continues into the fall - as appears likely in many states - anxiety and stress may be exacerbated, making it essential to implement stronger systems to meet the social and emotional needs of students and educators.

And even if school doors open in some communities, “we need to recognize that this pandemic will change people forever," Reamy cautions. "Some members of the school community will be mourning the loss of loved ones, while others will be mourning the loss of something else—their lives as they knew it.”

Learning Without Support Systems

The COVID-19 pandemic forced 48 states and the District of Columbia to close their schools through the end of the 2019 – 2020 school year. Students were cut off from friends. Other familiar faces—a favorite teacher, the bus driver who greeted them every morning, the counselor who helped them through the hard days, the cafeteria worker who served their lunch—were also suddenly absent from their daily lives.

The loss and isolation caused by the closures affected every student. But for many, school is a safe haven away from problems at home or other stressors. Being stripped of that sanctuary during the pandemic undoubtedly increased their anxiety, and many withdrew from online learning and communication with counselors during the closures.

The pandemic has disproportionately impacted communities of color, exacerbating not only existing economic and health care disparities, but also the stress and trauma experienced by many students in those neighborhoods.

“We’ve had so many students who have fallen through the cracks who will be returning to school without any support," says Kristine Argue-Mason, instructional resource and professional development director for the Illinois Education Association (IEA), which offers trainings on trauma-informed practices across the state. "They don't have the buffers - stable home lives, steady food supplies, outside support systems - that prevent stress and anxiety from becoming toxic and a major obstacle to learning. That’s what we really need to be concerned about as we head back to school."

The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color has magnified the trauma of Black and Latino students.

The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color has magnified the trauma of Black and Latino students.

Soon after schools closed, Lindsey Jensen—an English teacher at Dwight Township High School in Illinois and the 2018 Illinois teacher of the year—feared the COVID-19 pandemic was also a trauma pandemic in the making.

She understands how adverse childhood experiences—poverty, racism, violence, instability at home—fuel toxic stress in students and can jeopardize their emotional well-being and their academic success.

“I was up at night thinking about my students living in abuse and neglect, our LGBTQ+ students who are living in homes where they aren’t accepted for who they are,” she recalls. “I was thinking about students who don’t have access to basic needs, such as food.”

These concerns also weighed on Lee Starck, a K–4 school counselor for Stevensville Public Schools in Montana. During the spring, Starck immersed himself in trying to connect with his students through Zoom calls and other methods, but he couldn’t help but look ahead to the new school year with some degree of trepidation.

“We may not yet know the intensity of the trauma and anxiety,” he says. “We may not be getting a really accurate picture of what they’ve been experiencing. That’s unsettling to me.”

Educators In a ‘Dark Place’

Students aren’t the only ones in the school community who are coping with trauma. As a counselor, Starck is also an advocate for the emotional support needs of educators. “We can’t be neglectful of our staff feeling whole as well,” he says.

Teaching is already one of the most demanding and stressful professions. Educators have had to manage distance learning - a shift that occurred practically overnight - while facing the same stressors everyone else is navigating. "Most educators would admit feelings of loneliness and isolation, as well as helplessness," says Jensen.

During an April webinar on covid trauma and educator resilience, co-sponsored by the National Education Association, José Vilson, a middle school math teacher in New York City, talked about the stress and anxiety he was experiencing living in what was then the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic.

"I listen at the ambulances as they drive by my window. You hear them every day and I sometimes can't help but think, 'Is it soon going to be my turn?'

"Without question, teachers are going to have to have some kind of support in navigating trauma-informed practice," says teacher Lindsey Jensen. "We are going to have students return to us in [mental and emotional] states that we’ve never experienced before."

"Without question, teachers are going to have to have some kind of support in navigating trauma-informed practice," says teacher Lindsey Jensen. "We are going to have students return to us in [mental and emotional] states that we’ve never experienced before."

A few weeks after schools closed, the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence (YCEI) invited educators to describe the emotions they were experiencing. More than 5,000 educators responded. Over and over, the same words bubbled to the top. Stressed. Anxious. Worried. Overwhelmed. Confused.

Teachers were in a dark place, says Christina Cipriano, director of research for YCEI. “It's a daunting reality … the requirements for distance teaching and learning, simultaneously supporting all our students and their own families, managing waves of loss on a scale unimaginable, all the while under a veil of ambiguity about the future.”

In recent years, district and school leaders have generally become more conscious of and sympathetic to teacher stress and burnout, as well as its adverse impact on the profession and students.

This awareness shouldn’t fade when schools reopen. But with the Trump administration and many lawmakers pushing for a return to full-time, in-person learning this fall, Jensen wonders where the high praise for educators, so prevalent in the first few months of the pandemic, has gone. As the pandemic shows few signs of abating, educator concerns over reopening - shared by most parents - are being largely ignored in many communities.

“The lack of respect at this time is astounding,” said Jensen. "What if a student or educator dies? Are we going to receive the resources we need to provide extra social workers and counselors to help students and staff navigate that unimaginable trauma?"

In May, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the HEROES Act which provides critical funding to help schools reopen more safely and help alleviate budget cuts that could affect countless educator jobs. The U.S. Senate, however, has so far refused to do its part. According to an NEA analysis, as many as 2 million educator jobs - many of them school counselors and psychologists - could be lost over the next three years if Congress doesn’t act.

Prioritizing Social-Emotional Learning

Too much of the current debate around reopening, Cipriano says, has been marred by "mixed and inconsistent message that are having devastating effects on the emotional well-being of teachers, students, and families." And merely putting students back into their classrooms, sitting at desks ignores the other conditions that create safe and productive learning climates.

"We need warm, welcoming environments, where students feel connected and safe, and teachers feel supported and valued...and where we can focus on building and sustaining meaningful relationships that transcend the physical walls of classrooms," she says.

And that means prioritizing social and emotional learning (SEL). “It is next to impossible to expect teaching and learning to occur in a crisis without attending to our emotions,” says Cipriano.

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) defines SEL as “how children and adults learn to understand and manage emotions, set goals, show empathy for others, establish positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.”

Long before the pandemic, SEL had already graduated from mere “buzzword” status to being an indispensable fixture in a growing number of classrooms. But the impact of the COVID-19 crisis underscores the potential value of a more systemic implementation of SEL strategies - and not just for students.

“The emotional strategies that help our kids can work for us as well,” says Louise Smith.

CASEL recently surveyed 37 state education agencies to gauge any heightened interest in SEL. The results were very encouraging (see chart above). The states also identified the various obstacles to implementation, including the exclusive focus on academics, lack of staff training, and lingering confusion over what SEL really means.

It's well worth the time, effort and resources to navigate these challenges. Paying attention to the SEL needs of students and educators alike will be essential as schools begin to open their doors (or even if they don’t), says Kathleen Minke, executive director of the National Association of School Psychologists. “These skills are so important because they build trust, and that will help put kids in a space where they can begin to achieve academically again,”

During the school closures, Jensen was frustrated at what she regarded as a myopic focus on academics at the expense of emotional support for students. In the upcoming school year, she'll be transitioning into a new hybrid position that she hopes will create a larger space for students to address their emotions. Jensen will spend half of her time as a classroom teacher and the other half creating professional development opportunities for her colleagues. Her number one priority: Training for her colleagues on social-emotional learning.

"We will be infusing SEL into everything. It’s the most important thing we can be doing right now.”

Building that Familiar Community

Schools may want to reserve time as school begins to beging addressing the emotional well-being of students and educators, according to NEA's guidance on reopening schools, released in June.

"Consider suspending academic instructional activity for two weeks to start school with a focus on social-emotional learning activities that includes trauma screening and supports to help students and adults deal with grief, loss, etc.," the guidance says. "Social-emotional supports should then be continued throughout the school year and be integrated into students’ regular learning opportunities."When she’s back in the classroom, Smith says she will talk about grades and achievement, but not before she can provide a place where students feel comfortable.

She reminds herself that “moving forward” with grief or loss is better than just “moving on.” Smith recalls that despite how resilient students were when they returned to school after Hurricane Katrina, they looked to the adults in school—the teachers, the cafeteria workers, the school custodians— to see if they should be afraid.

“I want to be able to ask them, ‘What do you need to tell me? I may not have the answer, but it can help to talk. You’re not alone.’ We need to re-establish those bonds and help build those safe places, that familiar community," Smith says.

Without the attention to new programs to better serve the emotional needs of the school community, the educational progress of students will suffer, counselor Reamy warns.

“We are going to need more counselors in schools, more clubs and activities that address social-emotional health. And more training for the staff to help them recognize and address the difficult emotions experienced by both students and staff.”

Although students will crave the community and sanctuary schools provide, they are probably not aware of how difficult the transition is going to be, adds counselor Lee Starck. “We have to make them feel safe again. They’ll want that structure and sense of normalcy, but we have to understand how challenging it will be given what they've been through, what we’ve all been through.”

Resources

NEA and its affiliates are finding ways for schools and educators to address the issue of trauma and its implications for learning, behavior, and school safety. Learn more about adverse childhood experiences and trauma-informed schools.

In July, CASEL released Reunite, Renew, and Thrive: Social and Emotional Learning Roadmap for Reopening School. The result of a collaboration with 40 partners, including NEA, the document serves as a roadmap for school communities to embed social and emotional competencies and foster more equitable learning environments.

The Treatment and Services Adaptation Center offers online resources produced by a team of clinicians, researchers, and educators who are respected authorities in the areas of school trauma and crisis response.