After 34 years of teaching math and science at Farragut Community High School in Fremont County, Iowa, Harold Dinsmore officially retired in 1992. Nine years later, he “retired” again, after he was called back to finish out the 2001 school year while administrators found a permanent chemistry teacher. In 2015, he went back again to close out the school’s last semester. This time, there would be no going back to the town’s only high school.

Last summer the school—a fixture in the community, since its creation in the 1920s—was "involuntarily dissolved."

“It tears me up. It shouldn’t have happened,” says Dinsmore. “I was fortunate to have all my children go to that high school, and I’m very proud of [it].”

Dinsmore says his colleagues were proud of the school, too, and their pride made them active in the school’s life. “We all worked together and all of our school programs were strong,” he says, noting that when there was a game, Farragut’s bleachers were usually filled to capacity. “The school gave everyone a great foundation to succeed in life,” he adds.

Hometown Pride

Farragut is a small farming town established in 1870, and named after Admiral David Farragut—the nation’s first vice admiral to the U.S. Navy. He is remembered for making the cry, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead,” (paraphrased) during the victorious 1864 Battle of Mobile.

We all worked together and all of our school programs were strong. The school gave everyone a great foundation to succeed in life” - Harold Dinsmore

Dinsmore’s daughter, Marcia Johnson, lives and works in Shenandoah—a neighboring school district—where she teaches third grade and serves as the local president for the Shenandoah Education Association.

Johnson attended Farragut in the 1980s, and her high school memories are fond. “I loved being in a small school. We were involved in everything,” she says, firing off a laundry list of activities from music to sports, and “all” of the school clubs. She knew everyone, too: classmates and their siblings, teachers and their children.

During Johnson’s era, the school was known for the girls’ basketball team, which traveled to state championship games every year. “That was our claim to fame,” she proudly says.

The classes that followed Johnson’s won state competitions in speech, volleyball, and softball. Trophies filled display cases. And graduates’ academic efforts led them to impressive professions in different countries.

“The kids who graduated from Farragut are all over the world, even though they came from a tiny place,” says Pat Shipley, a former Farragut teacher who has been UniServ director for the Iowa Education Association since 1994. “One of my prior students lives in Taiwan and is an engineer for a major petroleum company.”

Despite the school’s success, the district experienced a slow and painful fall that led to Farragut’s closure.

The Collapse

The school was part of the Farragut district within Fremont County, which houses multiple school districts. In recent years, some of them operated in the red, and struggled to comply with state regulations. Steady enrollment declines made matters worse.

Farragut’s budget was overspent, and the district was noncompliant with the state’s accessibility regulations. To address these issues, the Iowa Education Department advised that the district merge with the nearby Hamburg school district, which was also struggling financially. In Iowa, the practice is called “whole sharing,” and is intended to help keep costs low and schools open.

The districts agreed. In 2010, they merged sports teams—a big point of contention for the respective communities, which were used to being athletic rivals.

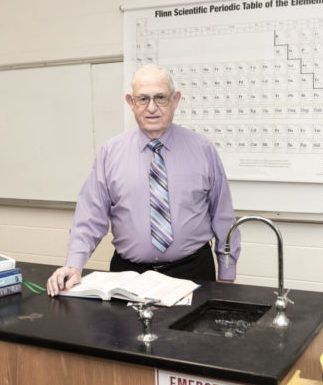

Harold Dinsmore

Harold Dinsmore

Patty Bredensteiner, a former art teacher, remembers the angst. “Community members didn’t like this change. In their minds Hamburg symbolized Wildcats and Farragut represented Admirals [the schools’ mascots].”

The two districts soon shared programs and students, and there were transfers of entire grades between the two schools. By 2015, seventh through twelfth graders from both districts became part of a new school, Nishnabotna, with a new mascot, new athletic name, and a new identity.

“There was a period of adjustment as the two former rival school districts learned to function as one entity,” says Shipley, who taught at Farragut for five years. “The students made the transition; the communities did not.”

The longstanding pride of the two communities was jeopardized as the two districts worked toward a new identity. The shuffle of students to and from the districts created another dilemma: a dramatic increase in transportation costs. The districts were nearly 20 miles apart.

“It became an issue of travel time and money for gas,” says Shipley.

Not Without a Fight

Not Without a Fight

Despite the additional issues, educators were hopeful that their high school would be saved, and many rolled up their sleeves to join the fight for its survival. They distributed petitions, attended community meetings, wrote letters, and called state legislators.

“Our folks worked really hard,” says Shipley. “They did everything within their power to tell their story to get people to think differently. But you can have the best organizing plan possible, and sometimes the weight of the issues doesn’t allow you to get what you want.”

Farragut’s school district had made some improvements, but it wasn’t enough. In December, 2015, officials at the state education department made the decision to shutter the high school at the end of the school year.

Jane Wilson, a former French and Spanish teacher, remembers the day the announcement was made.

“It was like losing a family member,” she says. “We all gathered at an assembly. When they told us, jaws dropped—and then there was silence.”

The Aftermath

“This was a heartbreaking experience,” Shipley says.

Ball games, band concerts, dances, and graduation ceremonies were gone. For alumni, there would be no more trips to the school for class reunions that had spanned three generations and occurred every five years.

Educators were understandably concerned about employment and health care coverage.

“My husband and I were on Farragut’s health insurance plan,” says Wilson, who taught for 35 years. “Once the school dissolved, we lost our insurance and had to go into the market place. We now spend a third of our income on insurance.”

The dissolution caused some teachers to retire early while others were hired by neighboring school districts. “There was widespread sensitivity from other districts,” says Shipley, “and those who wanted to teach found new places without making huge moves.”

The town itself also suffered. Farragut saw a decline in businesses and a reduction of car and foot traffic. At the local bank and the post office, operating hours were cut in half. Only the gas station maintains regular business hours.

“If you go up Main Street, you’re lucky if you see a car,” says Dinsmore, the thrice-retired Farragut teacher. Today, he is a Hamburg bus driver. “There’s nothing here,” he says.

Typically, when small, rural schools or districts shutter it’s a hard blow to the area. “It usually turns the area to ruins,” says Marcia Johnson.

In Farragut, community members worked to prevent that kind of fate.

Rebirth

Although Farragut Community High School sits empty today, when the district dissolved, ownership of the building transferred to the Shenandoah Community School District, which immediately sought a new owner to take over the property.

An initial attempt to sell the building to an Iowa manufacturing company failed when city council members rejected a rezoning. In December, 2016, success arrived when local business owners Trent and Donna Tiemeyer bought the building for $6,000, and began making plans to convert it into apartments.

People are positive with the new plans. Sometimes you have to think outside of the box to save yourself” - Jane Wilson

For Trent Tiemeyer, the work is personal. He graduated from Farragut in 1987. His grandparents, parents, and aunts and uncles are Farragut graduates, too.

“When my aunts and uncles were here for their last alumni celebration—when they knew the school was closing for good—my aunts were crying, saying, ‘This is the last time we’re going to be able to see the school.’”

Tiemeyer, who recently lost his mother, remembers thinking, “I’m going to do this for my mom. I’m going to keep the building, and not let it go to an industrial building or become vacant and get torn down.”

The Tiemeyers have a few ideas in mind for turning the building into an apartment complex that could draw families back into the community.

“There’s a wide area that was used for the lunch room. It has a kitchen. We’re considering a restaurant. People here drive for food, and if it’s good food, they’ll drive 40-plus miles,” says Tiemeyer.

The family also hopes to open the gymnasium to the community. “Kids could play basketball and tenants and residents could lift weights,” he says.

Local residents are excited about the apartment complex.

“People are positive with the new plans,” says Jane Wilson. “Sometimes you have to think outside of the box to save yourself.”

By creating more of a bedroom community, Wilson is hopeful younger families will move into the area and jumpstart a community that is fighting to stay alive.

Photos: Dennis Rogers