Key Takeaways

- Even with the best laid plans, most people's financial maps often need a tune-up— or a complete overhaul—after people retire.

- Educators must get accurate information and be realistic and honest about their assets and income as they get into their retirement years, being thoughtful about their risk tolerance.

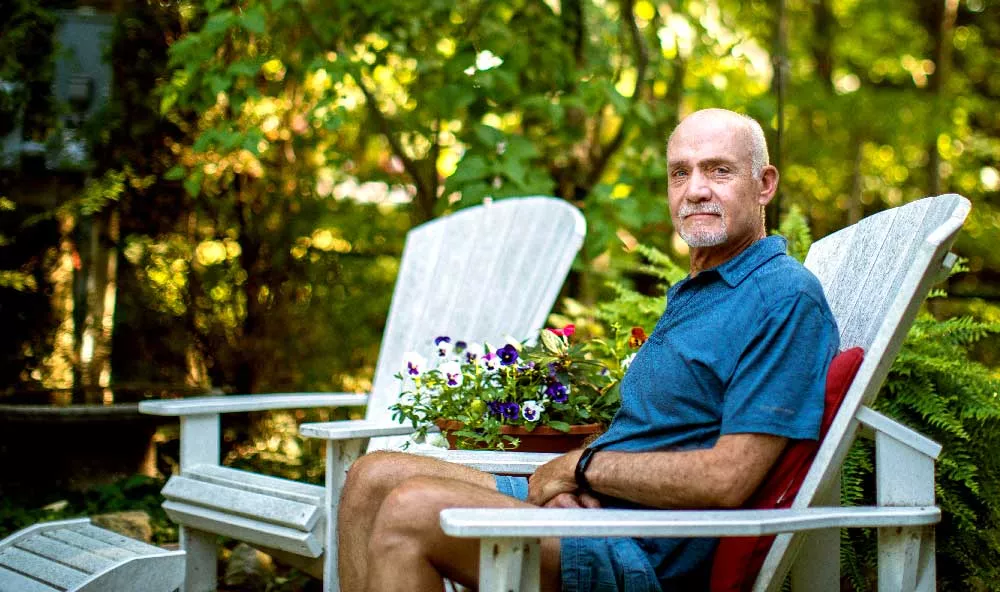

When Eric Dreier realized at 70 that he could no longer climb tall ladders, it was one more lesson about way things change in later years.

“I’d always painted my house, but when I had to have someone do it for me the first time after I retired, I realized there would be other things I couldn’t do myself,” says the retired teacher from Traverse City, Mich. “It’s one of many things … we don’t always think about. We need to plan for those changes.”

Dreier had a financial road map designed to take such things into consideration. And he has helped hundreds of educators build their plans, too. After Dreier retired from teaching math and science in 2006, he had a second career as a financial planner with NEA Member Benefits, which offers retirement planning services to members of NEA and NEA-Retired.

“I’ve talked to people who believe they will be paid out $50,000 a year when actually it will be about $30,000 net. A light goes off, and they recognize they have to have a new plan.”

Even with the best laid plans, he says, the financial map often needs a tune-up— or a complete overhaul—after people retire.

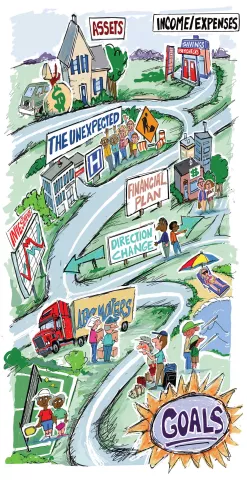

Like many financial experts, Dreier advises thinking about retirement planning as a road trip with a starting point, a destination, detours, missed turns, and stops along the way. Think of your map as your GPS to help you get back on track when things go awry.

The starting point

Financial planning begins with an understanding that circumstances change in retirement.

“You’ve had a good savings and investment plan. Now you have to look at your plan for spending more closely,” Dreier adds, noting that educators are sometimes unrealistic about their savings because they typically have a pension.

“I’ve talked to people who believe they will be paid out $50,000 a year when actually it will be about $30,000 net,” he says. “A light goes off, and they recognize they have to have a new plan.”

Educators must get accurate information and be realistic and honest about their assets and income as they get into their retirement years, and be thoughtful about their risk tolerance, he advises.

Financial expert James DiLellio agrees. When our careers are in full swing, we only have to consider how much money to save and where to invest it. But after retirement, it gets much more complicated, adds DeLellio, who writes about financial decisions in retirement and is an associate professor of decision sciences at Pepperdine Graziadio Business School, in Malibu, Calif.

Once you retire, there are many more decisions to make, he says, such as how much to withdraw, asset allocation, when to draw down a pension, and when to begin Social Security benefits, among other considerations.

DiLellio suggests that educators consider working with a financial planner. He recommends interviewing several and making sure you fully understanding the fees and whether the person fits your needs. For example, the planner should have an understanding of teacher pensions and 403B plans specifically.

Dreier also recommends using online retirement calculators that assess financial security in retirement. They can help you determine where you stand financially, and consider your assets, income, and risk tolerance.

Retirees may want to take their plan for a test drive.

“When someone had an idea about what they would have in income during retirement, I’d tell them, ‘Let’s practice,’” Dreier says. “I’d suggest they live on that income for a few years and see how it works.”

“When you are generous and care about your family, you assist them, but you have to be very careful about making those types of commitments.”

—Vickey Range, president, Louisiana Association of Educators-Retired

Detours and rerouting

Bumps in the road are expected in any retirement map. Dreier says his newfound reluctance to paint his house or undertake other home maintenance is exactly the type of shift that people should anticipate.

Retirees may need to help parents or a spouse, or they may have their own health issues that can have a major effect on their finances. They also must consider whether they want to leave money for family members.

When Vickey Range retired from Louisiana’s Caddo Parish Public Schools, she knew she wanted to support her family, but she also needed to be careful about risking her own financial security.

“There are so many needs a family might have, and it’s easy for us to want to help,” says Range, who is now president of the Louisiana Association of Educators-Retired. “When you are generous and care about your family, you assist them, but you have to be very careful about making those types of commitments.”

She and her husband, who retired from the military, wanted to get a new house and travel, so they have been conservative with investments and careful with spending.

“I think the biggest mistake is being frivolous with spending and not understanding your circumstances,” Range says.

Another unpleasant consideration that can throw you off course is cognitive decline, says Chris Heye, who founded Wealthcare Planning and writes about the impact of mental acuity on financial management.

According to the National Institutes of Health, about 14 percent of people age 71 and older have some form of dementia.

“Even normally functioning adults can have trouble because of loneliness, depression, anxiety, and just a normal loss of executive function,” Heye says. “It just gets harder and harder to stay organized and stay on top of these things. Cognitive decline is often the elephant in the room with financial planning.”

Heye suggests involving trusted family or friends in decisions and plans about finances and health, so they can help if your abilities decline.

“We were careful about planning,” Range says. “But we are realistic about how things can change with our health or other circumstances. We know it may have to be adjusted.”

As Dreier likes to say: “Just make sure there is a spare tire.”

Traffic jams

Robert C. Carlson, author of The New Rules of Retirement and the e-newsletter Bob Carlson’s Retirement Watch, among other publications, says outside changes can impact your retirement as well. For example, revisions in the law, tax hikes, and fluctuations in benefits or investment markets can impact your plan.

“A retiree must be alert to changes and be ready to adjust the plans,” he says.

Retirees have less time to recover from a sudden downturn or a bear market and are reliant on Social Security and pensions.

“Decisions we make are less forgiving,” Carlson says. “Retirees also need to be aware of what I call stealth taxes—provisions that impose additional taxes or reduce tax benefits when incomes exceed certain levels.”

Some common road blocks to look out for? Social Security benefits are added to gross income and can increase your tax rate; the income- related monthly adjustment amount can lead to a surtax on Medicare premiums; investment income over a certain amount can be taxed at 3.8 percent; and the minimum distribution requirements from retirement savings accounts and pension plans can increase.

“Retirees often find that one seemingly unrelated move, such as selling an asset or taking an additional distribution from an IRA, increases taxes,” Carslon adds. “They need to monitor it and decide if they’d be better off changing investments, moving money to different types of accounts, or taking other actions.”

Different paths to your destination

Freeman Linde, a financial planner and author of the book 3D Retirement Income: Creating a Retirement Income that Outpaces Inflation, Outlives You, and Outperforms Others, says educators shouldn’t be too conservative with investments or overly confident about their pension and Social Security. Those programs may not be as well funded as some hope, and retirees have to take enough risk to grow their money.

“I see this a lot with teachers,” Linde says. “In pre-retirement they are OK with growth, but then after retirement, they want to preserve everything they have. And that can be the wrong mindset.”

If you don’t need the money for some time, you may be able to withstand market fluctuations. So carefully look at your goals and understand your risk tolerance, he advises.

If you are a healthy person, you retired young, or you are planning to work part-time in retirement, you might be able take more risk and gain more in investments over time.

But if you need to draw from your accounts right away for daily expenses, or if you have some immediate health concerns for you or family, you may need to lower your risk.

The amount you have is also obviously a factor, Linde says. One rule is that you should only invest the money you can afford to lose in higher risk investments

“It is a balancing act,” Linde says. “The important thing is that when someone retires, they look at all these factors and make a good decision that fits their very specific needs.

Create Your Financial Road Map

- Start to pack: Consider your assets and savings as well as any tax liability or risks they present.

- Get a map. Develop a plan that spells out how you will spend your money (regularly, or on extras, such as trips or RVs). Also look at how you will invest and potentially grow your resources through additional income and earnings.

- Plan for the long haul. Consider how things will change in retirement when you may be primarily spending, rather than earning and saving. Consider taxes, long-term care, and potential changes in Social Security and pensions.

- Anticipate detours. Allow for unexpected volatility in the stock market and real estate market, along with inflation or other economic changes. Plan for personal changes as well, including mental or physical health issues for you or a family member, and other emergencies.

- Be willing to reroute. Regularly check to see if the directions you established still make sense.

- Lock in your destination. Consider your goals in retirement, the care you might need later in life, and whether or not you intend to leave something for family members.

Learn More

NEA Member Benefits is here to help

As a member of NEA-Retired, you have access to financial planning resources, especially for retired educators, plus health insurance, and long-term care. To find out more, go to neamb.com/living-in-retirement.