It’s an all too familiar and misleading storyline— the failing public school and the educators who fail their students.

It goes something like this: The students, mostly Black and brown and low-income, continually struggle below grade level. Test scores drop for consecutive years; attendance is spotty; behavioral and disciplinary problems constantly interfere with instruction; and there’s little communication with parents.

Alarm bells sound. The state swoops in and wrests control, firing everyone—from the principal to classroom teachers to education support professionals—and handing control (and funding) to a for-profit charter school with no ties to the community. A few years later, nothing has improved. The system fails the students—again.

But what if the story unfolded this way? Having long recognized the impacts of poverty on their students and families, educators sound the alarm themselves. They know that unless the underlying problems are addressed, their students will keep struggling. So they join with their district, union, students, parents, and community groups in advocating against a state takeover or school closure. Instead they propose a transformation—a switch to the Community Schools Model.

As the school begins to assess and help meet the academic and basic needs of the students and their families, the school slowly begins to change.

Parents are welcomed into the school and visit often. Community groups offer health, housing, and hunger relief programs, as well as enrichment opportunities for students and families. The school becomes a hub of social interaction and support for the entire neighborhood. It is a place created by and unified by the community. Now, student achievement is on the rise.

This version of the story may sound like a fairy tale, but it’s a narrative playing out in more and more districts across the country.

“Community schools meet the social and emotional and academic needs of their students,” says NEA President Becky Pringle, who is calling for the expansion of community schools nationwide. “This is a model that can and should be everywhere.”

NEA’s vision, which is grounded in research, is that the Community Schools Model can reclaim the promise of public education as a gateway for democracy and racial and economic justice. What transformation story could be better than that?

A Vision for Change

Like any good story, a community school must have a good structure, and that starts at the grassroots, says Anna Grant, the community school coordinator at Lakewood Elementary School, in Durham, N.C.

“A community school is the pinnacle of union members, educators, administrators, and parents on the ground, figuring out how, from the bottom up, to transform a school,” she says. “There are lots of tools and strategies to do this, but if you want a districtwide strategy … , if you want transformation not by charter, not by fire and rehire, or other silver bullets coming from private companies, you need deliberate, engaging, inclusive, and very rigorous problem-solving.”

So what does this look like in everyday life? In a Milwaukee community, parents didn’t think it was safe for their kids to walk to school alone, so the school created a “walking school bus,” with staff escorting their young “passengers” each day. Attendance rates skyrocketed.

In Los Angeles, educators were buckling under the workload. Their community school partnered with a local organization to provide student enrichment during the day to give teachers extra planning time. Burnout decreased.

Examples like these abound. At community schools, stakeholders identify problems and work together to find solutions.

“Typically, stakeholders are the recipients of change and not the change agents,” says NEA community schools policy analyst Kyle Serrette. “When we empower those who are closest to the pain and mobilize them to be the driving force behind the solution, the byproduct tends to be sustained transformation.”

The First Step: NEA’s Community Schools Institute

The best way to make this vision a reality, Grant says, is to advocate for your local to join NEA’s Community Schools Institute (CSI), where members and leaders learn step-bystep how to build a community school.

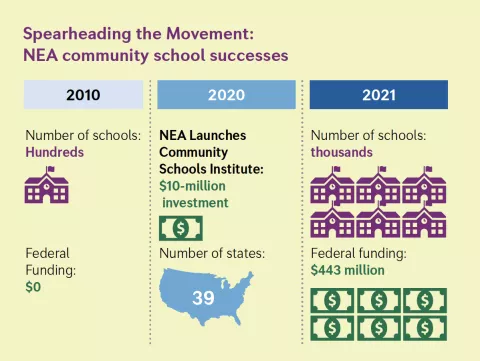

The CSI is comprised of two major components: The first, called the Strategic Campaign Institute for Community Schools, is the on-ramp for NEA local affiliates to build power and win funding for these schools. Locals also learn how to advocate for policies that support the schools’ success. The second part of the CSI focuses on best practices— which are based on data and research collected from more than 5,000 community schools.

“NEA has scoured the country to find the community schools who are doing the most inclusive and transformative work and are seeing results in academic data, suspension data, [and] school culture,” Grant says. “Reinventing the wheel is unnecessary and also impossible.”

Organize the Community

Schools transform by empowering everyone in the community, Grant says. She experienced this firsthand in fall 2017, while working as an interpreter and family liaison in her district. She had been meeting regularly with a group of stakeholders— including parents and community leaders— when two Durham elementary schools landed on a state takeover list, with plans to hand them to private charters. One of the schools was Lakewood, where Grant now works.

“There was a huge organizing effort, and parents showed up en masse to demand that no school be taken over by a charter,” she says. “But it begged the question: If a charter wasn’t the answer, what was? Community schools was the answer.”

To gain support, NEA funded a community school campaign organizer position, which became Grant’s next job. She built relationships in the school and community, and organized educators and parents around the model.

“We ran it like a unionization campaign, like a vote. And we had broad conversations about what staff and parents and community members wanted to see,” she says. “We launched a mini-listening campaign to show them what a community school model is all about—listening. We let everyone know that the school would become what they decided it would become. They would shape it.”

All of these stakeholders came from different perspectives, but they overwhelmingly voted to adopt the community school model.

And then the real work began.

“It takes long-term planning and being intentional about alliances,” Grant says, adding that this is where the CSI proves invaluable.

Ask What People Want and Need

Catherine Gilmore is the community schools coordinator at Gibsonton Elementary School, just south of Tampa, Fla. With the help of the CSI and its data-driven strategies, the Hillsborough County School Board voted to expand from two to nine community schools with plans for additional sites in the future.

Once a school community starts their deep dive, Gilmore says, the CSI offers the support of experienced community school coordinators across the country who coach local personnel.

“Every month we come together to share ideas, ask questions, and offer support,” she says. “You aren’t alone. If you struggle, someone who has experienced the same challenge is there to help.”

Through this knowledge-sharing, Gilmore learned that educators have to deeply understand the challenges facing students and families to find solutions.

“Before becoming part of a community school, many educators at my school … made assumptions about the community, students, and families in their effort to help,” she says. “When you stop, ask questions, and genuinely listen to the answers stakeholders offer, you realize that small, simple changes can create large improvements.”

For example, to address chronic absenteeism, the school staff increased communications with parents, alerted them to the number of days their children missed and how it affects their learning. That small change increased attendance by nearly 70 percent in three months.

Educators also wanted to create two-way communication, rather than just sending notices home with no response needed. They began asking questions and requesting feedback that parents could give in a variety of ways, by email, text, forms, or phone calls.

The parent response rate increased from 55 percent in September 2020 to 87.5 percent in March 2021, building stronger relationships between families and the school. As a result, more families now look to the school community for support.

Earn the Community’s Trust

Los Angeles educator Maishi Walker Deen learned an important lesson early in her career: If you are afraid of the surrounding community where your students live and you teach, you shouldn’t work there. She lives that lesson now as a community schools coordinator. Becoming a trusted and integral member of the community is at the heart of what makes the model work.

Deen started out at Dorsey High School, in 2018, as an English teacher. She specifically chose the school because of its predominantly Black student population.

“I wanted to work in a space where students could see someone who looked like them,” she says.

She had taken professional development classes in some of LA’s public housing developments, allowing her to gain insight into the hopes and dreams of the students who live there as well as the challenges they face.

That was the same year that UTLA went on strike, and Deen was thrilled that the expansion of community schools was on the list of demands.

When the community schools position became available for this school year, it seemed like a natural fit for Deen. But she felt immediately overwhelmed by the monumental task before her. Thankfully, the CSI taught her that not everything has to be done at once. The work is ongoing and evolving.

Deen learned that the first year of building a community school is all about assessing needs. What does everyone want or need? What does everyone already have? What skills and resources can be provided to the community by each stakeholder?

She soon discovered a wealth of resources offered by local organizations that schools could tap into. “I like to put puzzles together, and I am connecting needs with passions,” Deen says. “All of this has to be done in steps, and that’s why I so appreciate the CSI.”

She’s also gratified that NEA appreciates her in return.

Last fall, NEA President Becky Pringle met with Deen and several other community school coordinators at the UTLA headquarters, in LA.

“When Becky came, that’s when it became real. It was so special to meet the president of the NEA and the president of UTLA, and to be asked about our work,” Deen says. “And they were two women of color in charge of the whole thing. I’m a Black women, and it’s rare for me to see a reflection of me in leadership … . That was the cherry on top and the icing on the cake.”

Listening to the other coordinators who had started with the CSI, Deen says she knew she was on the right path.

“I felt totally supported by a roomful of people doing what I was doing,” she says. “That’s what the CSI is all about.”