Audrey Murph-Brown (Murph), a school social worker of 26 years and a member of the Springfield Education Association (SEA) in Massachusetts, describes the events that occurred in the 2017 – 2018 school year as “a perfect storm at the perfect time.”

This storm was heavy with institutional biases, nepotism, and favoritism. Institutional biases kept many highly qualified educators of color from becoming lead teachers or being offered lateral promotions. “Rarely were those opportunities given to educators of color,” says Murph, “but what they would get was the unspoken bias that only educators of color can deal with difficult children, and as a result don’t get to show their academic skillset and abilities in classrooms.”

And when there were opportunities for advancement, explains Murph, administrators would often bypass the hiring process by burying job postings, not interviewing qualified candidates of color, and handpicking their friends. “This was nothing new,” she says. “It’s always happened, but it’s never been addressed.”

The Initiative was an outgrowth of the Next Generation Leadership Program, which ALANA leaders and allies had previously attended. Next Generation was designed to create a safe space to talk about the issues educators face and it helps to identify, recruit, and train members to be active at the work site level, resulting in local affiliates becoming powerful and effective organizations. The program is unique in that it works with educators with three years or less of leadership experience, and that it’s mostly conversation. There’s no agenda other than the topics participants bring up. There’s no PowerPoint. No flipcharts.

“It’s all based on the lived experiences of educators, which helps to create the kind of space where people can build confidence in that change can happen through collective action, and learn the skills to bring people together and overcome their fears of taking action,” says George Luse, who, at the time, was an MTA organizer before his retirement.

He explains that the blueprint of the training does what it’s supposed to do: give people skills, encourage them to act, and build collective member power. “Nothing works without members who are excited about the union and understand the union as a tool to improve their working conditions and the environment around them,” says Luse, who has 30 years of organizing experience.

And that’s exactly what happened.

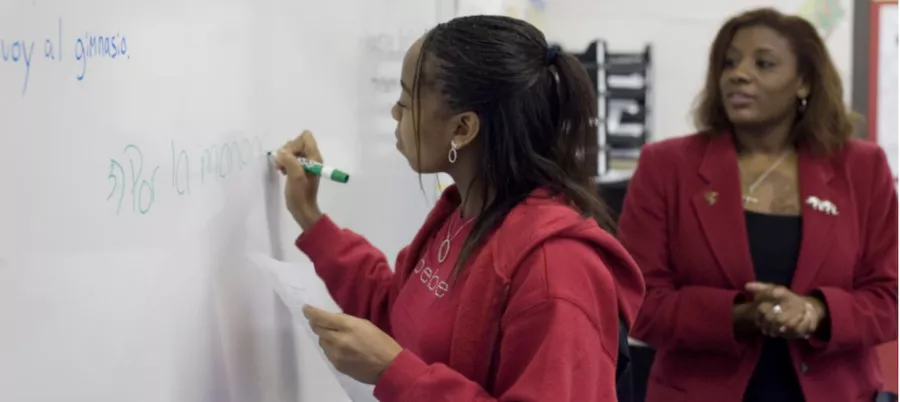

Educators from Springfield, Massachusetts overtake the local school committee meeting demanding an end to nepotism and institutional biases.

Educators from Springfield, Massachusetts overtake the local school committee meeting demanding an end to nepotism and institutional biases.

Welcome, ALANA

When Murph and other members completed the Next Generation program, they left saying “Yes, we can do something,” and from there, ALANA (African American, Latino, Asian, and Native American) Educators and Allies was born.

ALANA is an arm of SEA and was established to create a supportive, dynamic, and collective group, focused on building a diverse and culturally proficient environment for educators of color within Springfield Public Schools while empowering ALANA/SEA educators.

When the 2017-2018 school year started, Murph and others began to spread the word about ALANA, asking educators of all colors and backgrounds to join their efforts. These early outreach efforts were fun, informal social events. And then, it happened again.

The district hired eight behavioral specialists, none of which were educators of color. By this time Luse had retired, but with their new Next Generation skills in hand, ALANA members immediately took action.

The group conducted a survey and discovered that many educators of color didn’t know about these positions. Those—with years-worth of experience, graduate or doctorate degrees—who had applied were never called for an interview. “People were becoming agitated,” shares Murph.

But the defining moment for the core group of ALANA members came when a veteran educator of color was told via email on a Thursday night to report on Friday morning to H.R. Come Monday the educator would report to a different school building, making room to hire the relative of a high-ranking school administrator.

“We began to ask questions,” recalls Murph. “Where is the posting for this position? How are you interviewing candidates? Who are you interviewing? We focused on this one position because it was another blatant example of injustice, but this time, as a collective, we felt we could do something.”

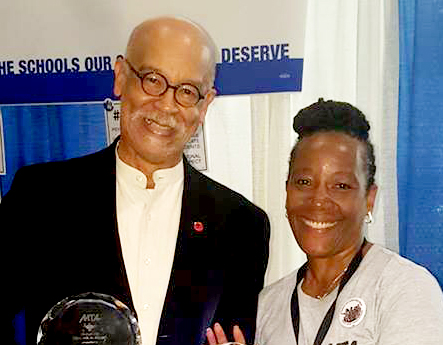

George Luse and Audrey Murph-Brown

George Luse and Audrey Murph-Brown

Additionally, public records requests were made to legally see who was interviewed. Explanations from administrators received pushback, but when all was said and done school officials changed the name of the position, posted the new position on the school district website, removed it from a national education job site, and then hired the relative under a new job title.

Murph says, “It was painful to watch that despite all of our efforts they were able to change the rules and get [the person] in.”

This upset didn’t deter anyone. When educators returned from winter break, it was time for “civil rights, get me arrested,” says Murph. The new year also brought George Luse, who was called out of retirement and went back to Springfield.

Springfield Educators Storm the Castle

Like any good organizer, Luse would have preferred more one-on-one conversations with educators and in many more school buildings. But, he says, “The issue of hiring and promotional practices has been a thorn in the side of many and now members wanted to act. It’s their deal so I laid out what it would take to do it and they did it.”

Six ALANA members and three non-ALANA allies originally made up the core of ALANA, and they knew they had little time to organize more educators.

The Springfield School Committee, the district’s legislative body, holds what they call Public Speak-Outs, where the public can come in and express their concerns. Only two are scheduled annually and the next and last one for the school year was in March.

Between January and March, it was an all-hands-on-deck approach to inform educators. Maureen Colgan Posner, president of SEA, was—and continues to be—extremely supportive of the group’s efforts. She provided floor time during general membership meetings and space in the SEA newsletter to explain ALANA and its members’ efforts.

By the time of the speak out, 90 educators filled the assembly hall, fired up.

“They’ve never had a collective raised voice before and we were bold,” recalls Murph, referring to the school committee. Educators and their allies held signs that read, “Fair Hiring for Everyone” and “No More Nepotism.”

Murph, one of the speakers that night, gave a powerful speech. She stood at the podium, telling school committee members that “we’re willing to assist you in building a diverse, credible school system. Recruitment efforts are only one part…we need to retain highly qualified educators [of color]…the system of nepotism and favoritism and the institutional biases and prejudices must stop now.”

After the speak out, the door to communication was cracked open and, since then, some actions have been taken. Principals, for example, must add a person’s ethnicity to the hiring process. The school committee’s human resource department is looking into the hiring process, too.

It’s been slow going, “but it’s more than what’s ever happened before,” says Murph.

ALANA and its members are continuing to organize, embracing people’s excitement and addressing the fears, concerns, and discomforts of others.

Come this school year, Murph and the team plan to continue to grow the base and they would like to see more school officials join their efforts. “We’re not the enemy. We want to be a part of the full educational system.”

Seven Elements that Make ALANA Successful:

- Support from the state affiliate. MTA leaders were very public and intentional about their mission of diversity and inclusivity and provided professional development through the Next Generation Leadership program and supported the local’s efforts by sending an organizer to work with the group.

- Support from the local affiliate. SEA leaders provided resources and a safe space for members to meet and have difficult conversations around race and privilege. Moreover, SEA leadership reduced their grip on the reigns, empowered, and supported ALANA members to take action on issues that are specific to educators of color and impact their profession.

- Constant and ongoing one-on-one outreach to ALANA members to ensure that the work of the union is consistent with the real needs of the members—in other words: good rank-and-file organizing.

- Outreach to school committee officials, including the school superintendent, to keep the lines of communication open.

- Community outreach to pastoral community and other grassroots organizations.

- The Springfield Public School system has also taken action: principals and directors are evaluated on their retention and promotion of educators of color; superintendent is evaluated on retention and diversity efforts of district; a mentoring program for new hires of color; ALANA members now have a presence during New Hire Orientation.

- The Springfield Education Association established a New Business Item, a bylaw to address the representation of an educator of color on the Executive Board of SEA.