Ask a retired educator why she decided to run for school board, and she will likely pause, as if the answer should be obvious. These positions are time-consuming, but educators are motivated by the same sense of purpose and passion that drove them to become teachers in the first place.

“Pride” was Joyce Haynes’ answer. After serving as a teacher for 40 years, she now sits on the school board in Louisiana’s St.

Landry Parish, where a quarter of residents live below the poverty line, and the median family income is about $23,000.

“I attended these schools and have a strong connection to them,” she says. “I want our students to have better facilities and pride in where they are from and where they are educated.”

For retiree Trudi Downer, who has served on elementary and high school boards in her hometown of Molt, Mont., for two decades, her background as an activist paved the way for her service. Plus, her children and grandchildren have attended local schools—including the K–8 school, where all levels are taught by one teacher.

“I felt I had the right experience and interest, and after serving, I’m even more optimistic now about what schools can do.”

According to the National Association of School Boards, women now make up half of school board members across the country. NEA Today talked with several of these women who are NEA-Retired members to find out how they are making a difference for schools in their hometowns.

Joyce Haynes: Speaking out for public school funding

Haynes has always been active in her local union and believed that she could have an even bigger influence on the school board.

“I learned so much in the union, and I felt I was playing a role in the direction our schools were taking,” she says. “I wanted to continue that involvement, and that opportunity arose when I retired.”

She says the underfunded and struggling schools in the district have caused too many students— and their families—to lose faith in the education they receive.

Changing that became a priority for her and a campaign mantra.

The election training she received from NEA’s See Educators Run program and her state organization were key to her winning election two years ago.

She gained the skills she needed to campaign effectively, handle finances, and speak to the media.

“They helped me be ready to carry that message about the power of working together,” she said. “That was a theme for my campaign.”

Since being elected, she has spoken out at schools and community functions about the value of public education. While federal support is increasing, she worries that district schools will still be plagued by a lack of funding. They are facing competition from charter schools, a dwindling tax base, and an unwillingness in the community to support education. An initiative to increase school funding in the parish was recently voted down by a 40 percent margin.

Her priorities now? Finding funding and alternative ways to improve classroom materials.

Trudi Downer: An activist at heart

Downer’s experience as an educator and her dedication to improving schools won the respect of board members, even allowing her to play a mediating role in contentious contract talks, she says.

“After a difficult strike, we worked hard to move from confrontational to issue-based bargaining,” she says. “I really wanted the board and staff and students to work as a team.”

Downers’ activist spirit grew out of the political climate of the ‘60s and ‘70s, and specifically the women’s rights movement.

The current board now works cooperatively on broader issues related to staff and funding. They have also tackled some of Downer’s specific priorities, such as maintaining music instruction; supporting a school that could lose funding if enrollment drops to fewer than 10 students; and prioritizing an award-winning program to support students’ transition from school to work.

Downer wishes school boards would focus more on the needs of students rather than simply keeping taxes low. Having educators on school boards to reset priorities will help, she says.

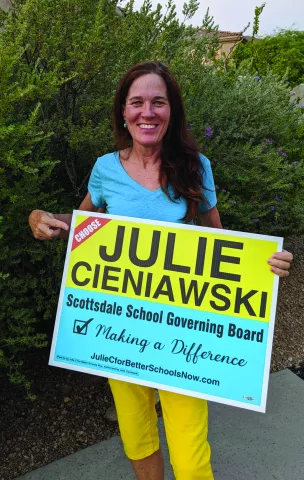

Julie Cieniawski: A passionate campaigner Arizona retiree Julie Cieniawski’s concern about the policies of the Scottsdale Unified School District School Board prompted her to run for a seat in November. The competition was intense, as she faced off against five other candidates seeking three seats in a highly divisive race about the future of the district’s 30 schools.

“A majority of governing board members didn’t even send their kids to our schools, and actually were trying to dismantle them. But as a bridge-builder, my focus was on moving forward. I knew our kids deserved better.”

She ran a lively, future-focused campaign costing about $16,000, with the support of a team of volunteers—many of whom were educators. She won the most votes of any of the candidates and now serves as board vice president.

Cieniawski and other new reform board members were elected on pledges to improve schools that had suffered from poor management and bad press. Staying true to these promises, the new board is reversing the previous administration’s policies that cut staff and discontinued recognition of the district’s three unions.

“Our public schools deserve to be revered,” she says. “Now, more than ever, our communities need glue to pull us together. Our schools can be that and more.”

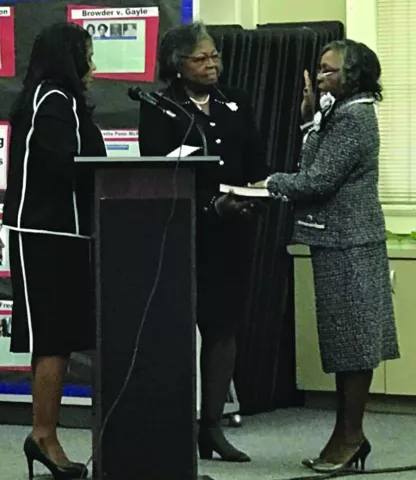

Brenda DeRamus-Coleman: Social justice advocate

For Brenda DeRamus-Coleman, who had 40 years of experience as a teacher and administrator in Alabama, running for the Montgomery County Board of Education came with a simple realization: “I was thinking about who had the right qualifications,” she recalls. “The characteris- tics I was thinking about sounded a lot like me. I think other retired educators would often find that is true.”

She says she discovered politics was not something she particularly enjoyed, but she determined that her genuine concern about education was a good selling point.

“I believe people wanted someone who cared about our students, and I showed them that was my priority,” she says.

DeRamus-Coleman has seen progress on two issues that are close to her heart: using restorative justice practices in schools and raising awareness about human trafficking, which tragically affects some of the district’s children.

She also helped pass a recent $9-million tax increase that will go toward schools.

“We have a great opportunity to move education forward with this sort of support,” she says, referring to the Biden admin- istration’s increased funding for education. “Change here and in Washington can bring schools up-to-date and make certain there are opportunities for all students,” she says.

Pam Baugher: Union veteran and school board president

Pam Baugher can tick off a long list of positions she has held with education organizations, including serving as an NEA Representative Assembly delegate for 17 years and as the first president of the California Teachers Association/NEA- Retired, a group she helped found.

She also attended nearly every meeting of the Bakersfield City Board of Education for more than 30 years.

“I always joked that when I retired, I should run. I had spoken there as an individual and rep- resenting the union, and I often felt I just got a smile and a nod.”

In her first campaign, which cost about $10,000, Baugher visited all of the district’s 41 schools, called registered voters, worked with the media, and attended community

Baugher had attended past board meetings as a union representative. So when she was elected to the board, she says,

“I made it understood I would look at things through a teacher’s eyes, but put the district first.”

She now serves as the board president and is still working to undo damage from the No Child Left Behind Act.

Mary Moe: Accomplished public servant

Mary Moe says retired teachers are uniquely qualified to fill positions where educational policy is made.

“Teachers make especially good public servants because they always have been,” says Moe, a former high school and college English teacher, college ad- ministrator, school board member, state senator, and current city commissioner in Great Falls, Mont.

Like Downer, her involvement grew out of her concern about education and the climate of political activism that inspired her as a young woman. But running for office took other skills.

“I never got over the aversion to knocking on doors, but it’s like eating spinach. You had to shut up and do it,” she says. “And raising money was surprisingly painless.

People want to feel they’re doing something. Donating to good candidates is the best way to feel that.”

Moe has a lengthy list of accomplishments from her years working on education issues. She played a key role in securing increases in teacher recruitment funding as well as $100 million for school improvement. She also worked to raise awareness about low-income students who were being unintentionally left out of co-curricular activities.

But like many of these retired educators, some of Moe’s biggest concerns are the lack of support for public schools as well as growing privatization efforts.

“There is support for public education, but I’m afraid that is eroding,” she says. “During my time in the legislature, the pressure from

Running for Office

Interested in running for school board? Here are some tips from NEA-Retired members who have run for office and won!

Dip your toes in. Some who have run suggest working on another person’s campaign first and attending board meetings before running.

A clear message. Experts in politics always say it is important to “stay on point” but that requires having a clear message first. Some suggest three simple priorities.

Consider your comfort. You will likely have to ask people to volunteer and seek support on the phone or door-to-door—and ask for money. Consider your comfort with those jobs.

Create a team. You’ll need support beyond family members—so get a group and formalize how much they will be involved.

Enthusiasm can decline. You’ll need a campaign organization with responsibilities assigned to specific people—and you’ll need to manage it or appoint someone to the task.

To build your campaign skills, check out NEA’s See Educators Run program, educationvotes.nea.org/see-educators-run/.