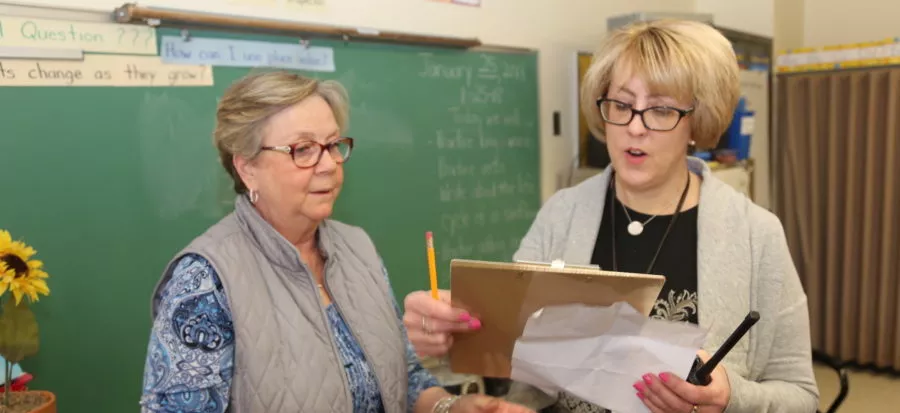

Nurse Sheryl Lapp (right) often meets with staff members like teacher Sandy Doyon to coordinate students’ health care needs.

Three students with food allergies are sitting at the nut-free table during lunch at John F. Kennedy Elementary School in South Plainfield, N.J. In accordance with a new school protocol, they have invited several friends to join them.

“It used to be that they could invite only one friend to sit with them,” says school nurse Sheryl Lapp. “But one student had several friends and couldn’t pick just one, so we worked to create an environment of acceptance instead of exclusion.”

Among some students, it is socially prestigious to have lunch in the peanut-free zone. Among teachers, food service workers, and paraeducators it is imperative to know the health plans of students with food allergies. They must also be trained to recognize symptoms of a first-time allergic reaction in a previously undiagnosed student. In case of an emergency, working as a unit is vital.

At Kennedy, teamwork, camaraderie, and mutual appreciation are the pillars upon which the school operates. This spirit of staff cooperation stems from the same impulse present at most if not all public schools: the desire to help one another succeed on behalf of students.

“It’s the tone of the building,” says teacher Sandy Doyon, vice president and building representative of the South Plainfield Education Association (SPEA), which includes 450 paraeducators, secretaries, and teachers. “We have great administrators and educators who put students first and know how to work together.”

Kennedy can boast almost 100 percent participation in SPEA.

“The folks here are very supportive of NJEA (New Jersey Education Association),” Doyon adds.

In Sync

At most schools, a principal’s leadership style pervades the buildings, playgrounds, cafeteria and all points in between. Whether positive or negative, it trickles down through the staff.

“Our principal is very supportive and fair, calm, and friendly,” Lapp says. “He can work with everyone here as well as the superintendent and board members.”

Principal Kevin Hajduk arrived at Kennedy in 2015 after serving as principal of South Plainfield Middle School.

It’s one thing to state that staff workers at Kennedy work well together. Educators at many schools do that. It’s another to see their teamwork reflected in the smallest detail."

“Kennedy was known for its progress on state assessments, great programs, and very supportive staff,” says Hajduk. “Immediately, you can see they are a close-knit group.”

It’s obvious that Hajduk’s loyalty runs deep. After all, he was born in South Plainfield and graduated from South Plainfield High School in 1995.

“We are a family-oriented team,” he says, “with students at the center of the discussion.” Of the school’s 55 staff members, only Hajduk and the physical education coach are male. The unity around gender may be a factor in the team’s success, though Hajduk chooses to credit each individual’s willingness to try new things, resolve disputes quickly, acknowledge each other’s strengths and weaknesses, address certain concerns in private, compliment each other on jobs well done, forgive one another when mistakes are made, and offer feedback when asked.

“It takes all of us, working together, to know our roles and to execute them effectively,” he says. “Respect, trust, and good team communication are our keys to success.”

School Hub

The second grader entering nurse Lapp’s office rushes past a teacher in Lapp’s office and blurts a quick “Hi.” The student is distracted by debris lodged in her eye.

“Let me see…don’t scratch,” says Lapp, whose multi-purpose office is a school hub of sorts.

The sun-soaked space includes a vast storage area for medical supplies and two private restroom facilities—one for hurried teachers and another for students who might experience a stomach-related emergency.

“Sometimes, it’s like I’m the school mother,” says Lapp, who joined Kennedy in 2013 replacing a nurse who had been at the school for 25 years.

“You never hesitate to ask Mrs. Lapp for anything,” says paraprofessional Juliann Bickunas. “She’s well-trained for the job and works well with everyone.”

In a corner across from Lapp’s orderly desk is a wheel chair, oxygen tank, and low-rise bed where students rest after Lapp has tended to a nose bleed, bruised eye, knee scrape, or puncture wound that could be located almost anywhere.

Even teachers are known to visit Lapp’s office for a quick consultation.

“I’m here for them, too,” she says. “Staff members consult me about their own pains, bumps, and bruises as well as those of their students.”

At Kennedy, Lapp works as closely with education support professionals as with teachers and administrators on the academic progress, and emotional and physical health of the school’s 280 preK–fourth graders.

“We talk a lot amongst ourselves,” says Amy Leso, third-grade teacher and a 2002 graduate of South Plainfield High School. “When I have a student with an allergy, I’ll mention it to other teachers and staff.”

Staff are trained to maintain student confidentiality but to also collaborate on care.

All for One

It’s one thing to state that staff workers at Kennedy work well together. Educators at many schools do that. It’s another to see their teamwork reflected in the smallest detail.

Custodian Marilu Hernandez, who has worked at Kennedy for six years, often collaborates with Lapp on choosing the safest cleaning products for students as young as age 5. They read bottle labels together.

“Always, students come first with Mrs. Lapp, the teachers, principal…all of us,” says Hernandez. “When a teacher calls me [after a student has an accident], I go quickly.”

Nurse Sheryl Lapp at work in her multi-purpose office.

Nurse Sheryl Lapp at work in her multi-purpose office.

Teacher Heather Hearne-Pascale says Hernandez and Lapp are familiar faces in her classroom of nine K–second graders with multiple disabilities. Each student has a different health care plan involving seizures, diabetes, or life-threatening allergies.

“The majority of my students can’t tell me what they’re feeling, especially when it comes to toileting,” Hearne-Pascale says. “We have a lot of little accidents.”

Five paraeducators work with Hearne-Pascale on helping students with everything from language and communication skills to toilet training and personal hygiene.

Outside the classroom, paraeducators are responsible for escorting the students to the cafeteria, gym, music, and other classes.

“All our teachers know these students by name,” Hearne-Pascale says. “We look out for each other and each other’s students.”

Special education teacher Brittany Lillis, who teaches third through fifth grade, also credits caring parents with helping to maintain a healthy school climate.

“We listen to them and they to us,” she says. “You get to know them, which helps us even more to serve our students.”

The margin for error regarding student health and safety becomes slimmer when parents are factored in, explains teacher Alicia Berardocco.

“Parents are very accommodating here,” she says. “We communicate on a daily basis with some of them.”

Crisis Contained

Last fall, Lapp had to rush out of her office to help a student having a seizure in a classroom.

“Most seizures last about five minutes,” she says. “This one went on for almost 15.”

Fortunately, classroom staff knew to remain calm, began tracking the time and the length of the seizure, monitored the student’s breathing and protected the student’s head until Lapp arrived and activated EMS.

“Our secretary knew whom to call…our maintenance staff were on standby to help with whatever was needed,” Lapp recalls. “We are very lucky that our school administration recognizes the importance of having a full-time nurse in the building.”

The student received efficient care and was back in class within several days. The student is among 8 percent of children in the U.S. diagnosed with food allergies. Of this group, 40 percent have the potential for a life threatening severe reaction known as anaphylaxis, which causes blood pressure to drop and airways to constrict.

Anaphylaxis can be fatal without rapid treatment. According to EdSource, a non-profit education news website, almost 20 percent of severe allergic reactions at schools happen to children who have not been diagnosed.

“Sometimes you don’t know until the first time,” says Lapp.

The incident at Kennedy was an example of the high level of collaboration and commitment to the health and safety of students.

“In a school environment that stresses communication and collaboration, I think you’ll find low levels of absenteeism and high levels of [staff] morale and student achievement,” Lapp says.

In Good Hands

Lapp maintains a drawer in the front desk reception area filled with student-specific and stock EpiPens organized in baggies. EpiPens are auto injectors with spring-activated needles and can be administered in a thigh through clothing. Each baggie contains a printout of the student’s medical history and photo, and the EpiPen.

“Many of our staff have been trained to recognize symptoms of an anaphylactic reaction, how to administer an injection and follow-up procedures,” she says.

The school’s specialized instructional support personnel (SISP) also collaborate on student psychological assessments and case management.

“She (Lapp) tests thoroughly,” says speech therapist Peggy Monagle. “The students we work with have many medical conditions which require in-depth knowledge of their situation and cooperation from everyone.”

School psychologist Ashley Kellett recalls the many cross-departmental meetings between social service workers, teachers, and others where student health issues are analyzed.

“With certain students, you have to determine what’s causing the (psychological) problems,” Kellett says. “For that, you have to be organized and work together.”

For More:

Nurse Sheryl Lapp and other staff from Kennedy are featured in a video as part of the Classroom Close-up NJ series sponsored by NJEA. The video premiers May 6. View here: classroomcloseup.org