Bill Lyne is a professor of English at Western Washington University and president of the United Faculty of Washington State.

It is tempting to look for facile historical congruences and imagine that this is what it must have been like in 1930s Germany.

The autocratic seizure of power from feckless bureaucrats; the scapegoating of racialized "others"; the creation of an unaccountable secret police force; the use of borders to stoke fears; the flagrant genocide; and the friends and neighbors turning on each other in fear of and obeisance to pallid power.

Depending on our position, our perception, and our pluck, we respond in a variety of ways. Some of the most materially fortunate tell themselves that this is the natural order; the world is better off leaving decisions to the unaccountable few. The least fortunate feel the daily erosion of their nervous systems as they wait in fear of the next no-knock warrant, the next roundup at Home Depot, the next climate disaster that steals the lives of their children. Those of us in between toggle between planning our next vacation and feeling like we're politically active because we listen to a Substack podcast or stand in front of a government building with a sign about ovaries or kings. We make sure that one of our cars is electric, donate to a Democratic Socialist candidate, and check out 401(k)s, and then tell our students to follow their conscience.

As what's left of the professoriate struggles with the question, "What is to be done?" we should move beyond reified one-liners about Nazism and toward a gimlet-eyed understanding of how we got here.

Donald Trump is neither new nor unique. While Barry Goldwater, Ronald Reagan, and George Bush—pére et fils—are obvious precursors, so are Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama. The massive economic inequality that created the conditions for Trump has driven the poll numbers for the Democratic Party even lower than the president's.

While ruling class cruelty and vulgarity are more visible now, Trump still has a ways to go before he catches either Bush Jr. or Obama on the deportation scoreboard, and the policies that have blossomed into the genocide we're witnessing in Gaza have long had the support of both Democratic and Republican elites.

While the Republican Party has capitulated to fascist populism (a term that in a saner world would be oxymoronic), the Telluride/Davos/New York/London Democratic leadership pushed a legitimate socialist alternative into the shredder in favor of the same old, same old.

As we begin to see the limits of pageants of protest, we should return to the kind of organizing around redistribution—and the real material interests of most people—that first led to the circling of the oligarchical wagons.

We must face up to the fact that U.S. universities have become mostly producers of what Thomas Picketty calls the "Brahmin Left," a technocratic elite focused on identity over inequality, providing little more than faux opposition to the "Merchant Right." But we should also remember that college can be a fertile site for the kind of organizing we need.

In the years following World War II, the combination of massive Cold War federal and state investment, the Gi Bill, and various civil rights and women's movements provided access to college for large numbers of people who had previously been excluded. While the Ivy League remained a finishing school for people whose places in industry, government, or the CIA were reserved, public colleges and universities became state-supported spaces where the tenured members of the bourgeois intelligentsia who talked about the consequences of capitalism could commingle, talk with, and listen to people who had actually lived those consequences.

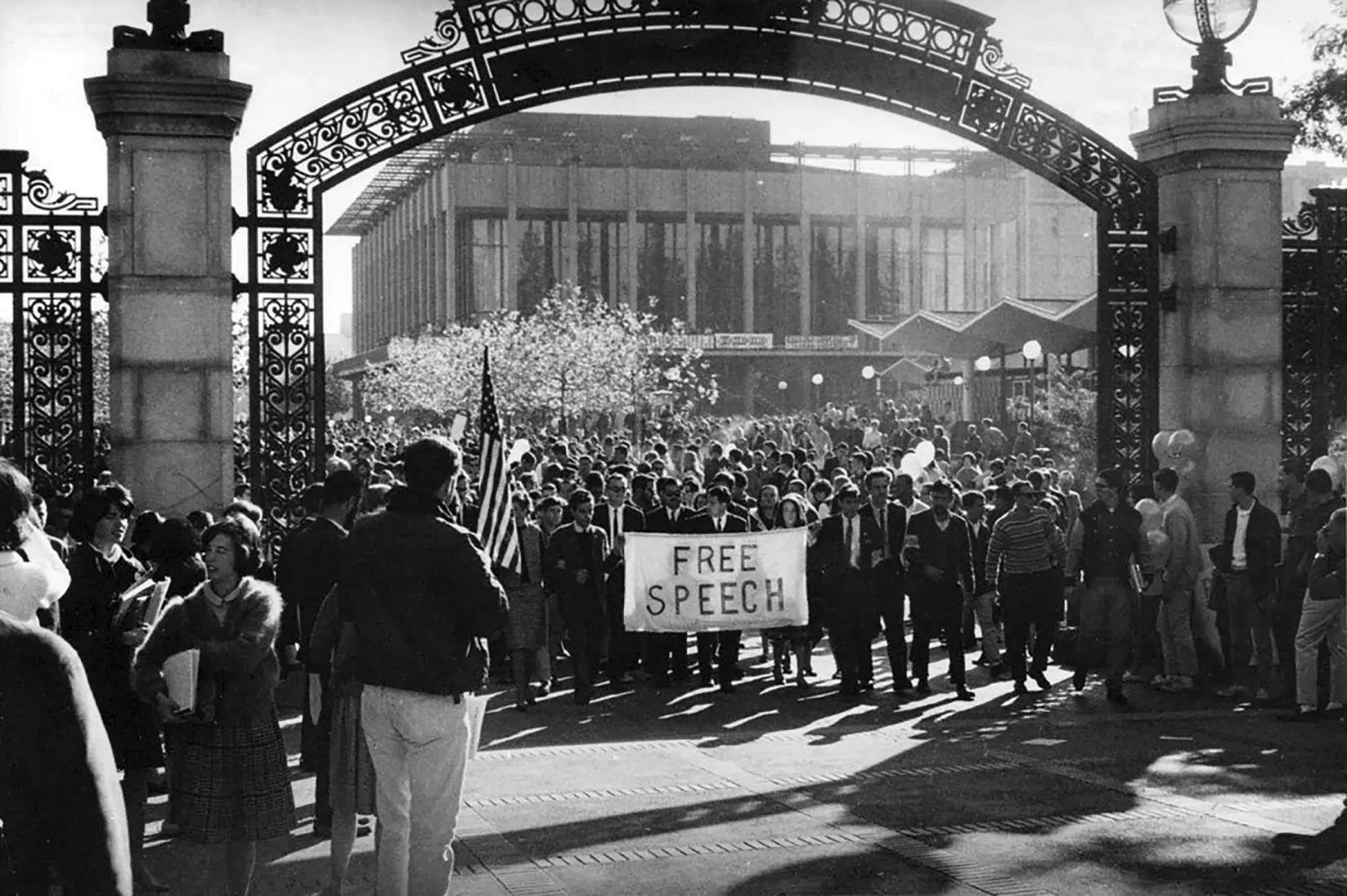

This led to a lot of things, including the creation of radical collective energy that reverberated beyond the campus. The guys who created the Black Panthers met in college. The Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement was nourished by the student newspaper at Wayne State University. The free speech and anti-war movements wouldn't have existed without the crucible of college.

We can debate the efficacy of these interventions endlessly, but one thing we know for sure is that they got the attention of the ruling class. Lewis Powell, in his infamous "Powell Memo" to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, spent a third of his manifesto lamenting the radicalization of otherwise perfectly reasonable young white men in college.

Reagan lubricated his transition from B-movie star to California governor by vowing to "clean up the mess at Berkeley." Powell and Reagan were the medicine-show hucksters, the noise to rile up an incoherent base (the equivalent of what Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and George Clooney represent to what counts as "the left" today), but the real damage to higher education was done by 50 years of patient (and bipartisan) organizing in think tanks, state legislatures, and Congress.

Between 1950 and the early 19702, college was as available to working classes as it has ever been. Since 1980, it has been increasingly restricted by a retreat from public funding and made available only to those with the time and stamina to pass through the intimidating keyholes of admissions and financial aid bureaucracy. What was once a public good—and a genuine threat to pull back the curtain on inequality and oligarchy—has become relentlessly focused on training for individual access to more and more precarious jobs.

Quote byBill Lyne, President of the United Faculty of Washington State

So, as we try to fend off the onslaught of attacks on the most vulnerable, which enrich the few at the expense of the many, we should use what power we have as unionized academics to restore access to the knowledge and community that could lead to a different arrangement.

Standing between our students and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; trying to shield our colleagues from payback for daring to say genocide; protecting academic freedom; understanding the implications of AI; and improving our wages, benefits and working conditions are all vitally important, but those are rearguard actions that would all be easier if college were genuinely free. We should focus what power we have left on the idea of college as a public good, available to anyone who walks through our doors. Free college was once a genuine threat. We should try to make it that again.