We found a plot of land with eight acres right behind our son’s house, and we made the decision to build a new home with everything we wanted on one floor,” says Maine retiree Jane Conroy.

But before she and her husband could make their big move, they’d have to dig through years of belongings—including many sentimental objects Conroy accumulated after her parents died. She would have to make some hard decisions about what to part with and what to take to their new home.

To help her tackle a seemingly overwhelming task, Conroy followed some simple rules. “For one thing, I realized that my kids would not care about a lot of the things I’d saved, so why should I burden them with having to go through it all or get rid of it,” says the former cooperative extension educator. “So, I worked on it a little at a time and had three piles—things I would keep, things I would pass along, and things I would toss. It felt so good when I got through it.”

Conroy, who lives in Dover-Foxcroft, Maine, says she kept items she enjoyed and had meaning to her, and passed down objects she thought would have meaning to others.

“I tried to think about things my kids and grandkids would want. I came across a letter my daughter had earned for cheerleading and cross-country running. Since my granddaughter is an athlete, I thought she might like it. She loved it and hung it on her bedroom wall.”

Getting rid of stuff, especially as possessions and memories have accumulated over time, is hard work emotionally and often physically, says Jenny Albertini, author of the book Decluttered: Mindful Organizing for Health, Home, and Beyond.

Want to jump-start your decluttering or downsizing projects—and still keep your sanity? Follow these tips from experts and fellow retired educators.

Prepare emotionally

“So much of the work …happens before the first box is packed up,” Albertini says. “It’s the emotional readiness that deserves the most attention and that will usually take the most effort.”

Albertini, whose mother was a teacher, notes that the work may be particularly difficult for educators.

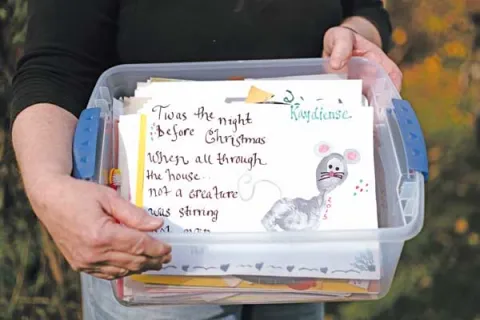

They often have an extra layer of “stuff” collected from their professional lives, like old textbooks and prized notes, gifts, and drawings from students, Albertini says.

“[They also] have demonstrated such tremendous leadership in their professional roles, that when it comes to homes and clutter, the idea of giving up control … can be very stressful.”

On the other hand, some take on the process with the same efficiency they used to run a classroom, she adds.

Retired social studies teacher Tammy Johnson, from Wales, Wis., says, “When I did it, I relied on a mantra I had regarding my classroom—I embraced throwing things away. We should pretend it’s the end of the school year, our grades are due, and we have to clean up our classroom, all in a few days.”

Identify your purpose

Antonia Colins is the founder of the blog and website “Balance Through Simplicity,” where she offers advice and resources to help others navigate this process.

“The things we own often carry memories, reminders of people, places, experiences, and moments in time,” she says. “So it makes sense that clearing it out takes a bit of reflection, patience, and soul-searching to work through the emotional side of letting go.”

It helps to focus on the value of decluttering, Colins suggests. For some, letting go of possessions will help them get ready to downsize. For others, it releases them from the burden of holding on to unwanted things. Still others may get inspired by the idea of having a more organized home, where they can actually find the holiday decorations without scrounging through the entire attic.

“Understanding the purpose gives clarity and motivation, especially when the process feels emotional,” she says.

Albertini tells clients to think of decluttering “as a chance to make life easier and more joyful for your future self.” Don’t take it personally if others don’t share your attachment to items.

Conroy takes that theory to heart. “It may be hard to recognize that our children are from a different generation, and many times could care less about things we value,” she notes. “Give them an opportunity to have things you think they might want, but don’t be offended if they don’t care about them.”

She adds, “Think about what memory something holds. Who or what does it remind you of, and is it important? Could you keep one representative piece instead of a whole collection? Could you take photos of items to preserve the memories? Could something be repurposed or displayed in a new way so it continues to bring joy in everyday life?”

“I have accepted the sentimentality I have toward some things. I want to keep the things that give me joy or fill me with emotion. I think that is important.”

—Utah Retired educator Debbie Green

Find a project pal

Cleaning out your closets with a buddy or family member can help keep your energy level up and help you make decisions, suggests Colins. But choose your decluttering partner wisely, she cautions.

Retired music teacher Debbie Green, from North Ogden, Utah, knows exactly what she means. “I have a deep attachment to things. My sister has none,” Green says. “We can’t understand each other when it comes to this and would have a hard time working on it together.”

Green lost five family members over eight years—her parents, in-laws, and her husband—and their possessions piled up in her home alongside the items she had collected from years of indulging her love of thrift shops.

But her daughters have helped her gradually thin out the possessions.

“If you are sentimental about things, it helps to have someone else say, ‘Yes, your granddaughter made these paper flowers, but do you really need to keep them? Do they mean that much? Will they mean anything to others?’” she explains. “You have to determine where you are on the attachment spectrum—if you can do it yourself, or if you need someone to help with decisions and keeping focused.”

Tackle a little at a time

Colins and Albertini suggest starting with less emotional items such as clothing, tools, or kitchenware.

“Decide what approach works best for your time, space, and energy,” Colins adds. “Take action, but start small, stay consistent, and keep your ‘why’ in mind.”

Albertini agrees: “Allocate time to work on it on a regular basis. It doesn’t have to be every day, but try to get into a rhythm, so that even for an hour per week you are connecting with this activity.”

Also, be sure to keep an eye out for important records that might be mixed in with memorabilia, and keep those in a safe place, they advise.

Have a storage system

A first step, Colins suggests, could be to plan for where to stash things, such as your attic, garage, or closets. Limiting space for certain items can motivate you to control what you keep, she notes.

Green, for instance, has a hutch devoted to memories of her late husband. At one point, she feared that in clearing things out, she was losing him. “I wanted to keep things … that reminded me of him, but I did it thoughtfully and have much of it in one place,” she says.

Establish guidelines

Embrace the one-year rule. If you haven’t used it in a year, toss it or give it away, experts advise.

For those shoe boxes full of photos? Digitize them, Colins says. They are easier to preserve and organize this way, and you can share them more readily with friends and family. Tech-savvy family members may be willing to help with this project, too.

Don’t hold the keepsakes of others. Instead, give children the option to take them, with an understanding that you are going to dispose of the items they don’t take, Albertini says.

Don’t feel guilty about “mistake purchases” that were expensive or haven’t been used. Give them to someone who can use them.

“Embrace change and the future,” Albertini advises. When it comes to personal items and memorabilia, be decisive and consider how you want your life to be in the future.

And if you can’t squeeze all of your “get rid of” items into storage boxes and bags, Johnson recommends renting a large disposal bag or dumpster from a company that will leave it in front of your house and haul it away when it’s full.

Johnson knows how difficult these decisions can be. “When discarding items, reminiscing over them is probably the hardest part,” she acknowledges. “You know at a glance whether you want something or not, so just make a decision.”

Go boldly forward

Organizing your home also provides an oppor?tu?nity to think about changing your habits.

Green says she has stopped visiting thrift shops as recreation and is more thoughtful about what she acquires and keeps. Some objects, she says, are worth keeping because they provide a valuable connection to the past.

“I have accepted the sentimentality I have toward some things. I want to keep things that give me joy or fill me with emotion,” Green says. “I think that is important.”

She has a glass pendant that a student gave her around the time she retired. She hangs it on the rearview mirror of her car, because it reminds her of all the students she has taught.

She says, “While many things probably aren’t worth keeping, that certainly was.”

6 Steps to Help You Get Started

Sometimes the hardest part of downsizing or decluttering is figuring out where to begin. Here are six expert-recommended steps to help you move from overwhelmed to organized—and ready to take the first step.

- Identify priorities. Develop a list of your target areas, organized by priority. Consider ranking each area by the estimated time involved or level of difficulty (which can be based on emotion or the magnitude of the task). Focus on one area at a time.

- Establish a pace and schedule. Start small. Recognize that this may take time and will be more successful if you break it up into manageable chunks of work. Consider setting a timer for your work sessions, so they don’t become onerous.

- Create four boxes—or five? Make boxes or piles for items you want to keep, pass on, sell, or throw away. Some experts recommend a fifth category—the “I can’t make a decision about this now” pile.

- Find helpers. Ask family or friends for help, or hire professionals, if your budget allows. This can be particularly useful for spaces or possessions that pose physical or emotional challenges.

- Allow for emotions. Sorting through the past often stirs up emotions, sometimes in unexpected ways. Give yourself permission to pause if the process gets difficult.

- Reward progress. Do something enjoyable after you’ve wrapped up your project for the day. This can help relieve stress and keep you motivated to continue the project another day.