In the spring of 8th grade, Joshua Sermon stopped going to school. He was living on the east side of Atlanta in a neighborhood that he won’t call very bad, but it was kind of tough. In that place, there didn’t seem to be much future in education.

“I just wasn’t taking it serious,” Sermon recalls. But one day, while he was out, Sermon’s principal called. And when Sermon returned home, “my mother was like, ‘You’re moving.’ She knew I was going to end up in jail. So she sent me to live with my dad. It was a big change — it was the best change.”

Today, Sermon is a college student—and not just any college student. He’s a dapper-looking junior at Winston-Salem State University, a historically Black university in North Carolina, where he serves as secretary of the Student North Carolina Association of Educators. Sermon plans to become an elementary school teacher and then keep climbing the ladder until he can call the office of the U.S. Secretary of Education his own.

“My life completely shifted. It’s amazing to think how it could have gone… A lot of my friends from middle school are on probation, wearing that thing on their leg. None of them are in college,” says Sermon.

Sermon isn’t the only first-generation college student to beat the odds. Detroit native Tabrian Joe, an education major and activist at Western Michigan University, remembers when his family went through six used cars during his high school years.

While half of people from high-income families will get a college degree by age 25, just one in 10 people from low-income families do.

While half of people from high-income families will get a college degree by age 25, just one in 10 people from low-income families do.

“I’ve seen my mom struggle,” he says. “Personally, I just always saw going to college as something I needed to do to be successful. I want to do better than my parents did. That’s just my mentality. I don’t want to stop. I want to get past any obstacles or challenges.”

When it comes to higher education, those obstacles are enormous for many students. Consider the 225 percent increase in tuition costs at public universities since 1985, or the 457 students, on average, assigned to each guidance counselor in the U.S. These burdens feed a college opportunity gap that leaves many Americans without access to the higher education they need to get good jobs. Unfortunately, Sermon and Joe are exceptional.

Rising College Costs

Although Americans often think of their country as a place where anybody can move to Easy Street through hard work and strength of character, the facts tell a different story. The reason we’re either rich or poor is simple: We’re born that way. In fact, a Pew Charitable Trust report shows that a mere 4 percent of people born into low-income U.S. households will ever become high earners.

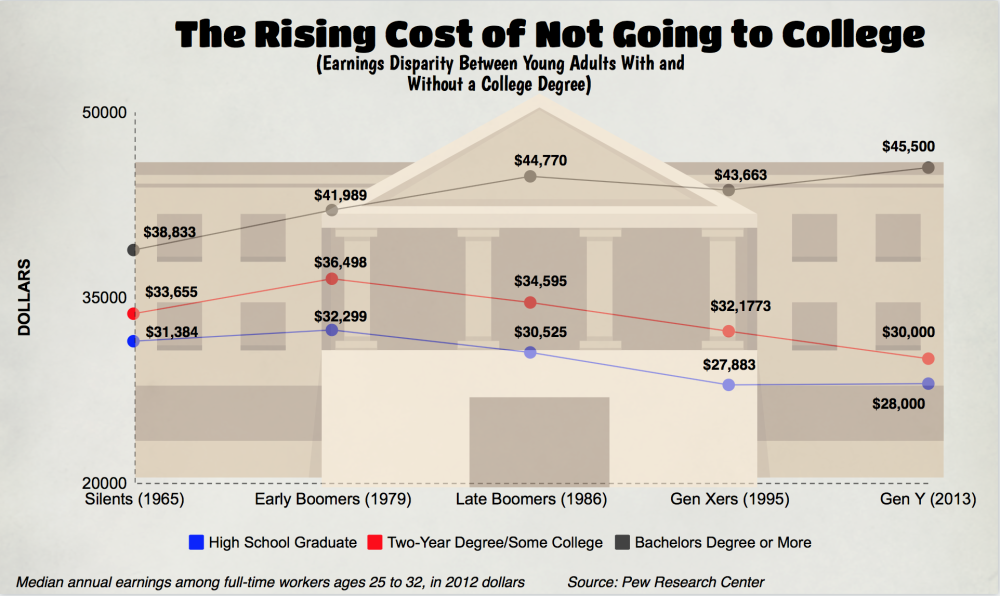

But of those who moved into the middle class at least, the single most common trait was a college degree. President Obama called it right when he said this year: “Today a college degree is the surest ticket to the middle class and beyond.” Whether it’s job satisfaction, employment rates, personal earnings, or almost any other indicator of economic well-being, people with college degrees have it better.

The problem is: Who can afford to get that degree? Not the poor. While half of people from high-income families will get a college degree by age 25, just one in 10 people from low-income families do.

Cost, of course, is a major challenge. As states cut funding for public colleges, families are stuck with the bill. A moderate budget for a student attending an in-state, four-year public university was $23,410 last year, according to the College Board. That includes tuition, food, and textbooks, and adds up to nearly half the average U.S. household income. Many families borrow to pay. But that’s a familiar story by now: Student debt in the U.S. topped an absurd $1.29 billion this year.

“Astonishing. Unacceptable,” writes NEA President Lily Eskelsen García on a post to her blog, Lily’s Blackboard, which asks readers to join NEA’s Degrees Not Debt campaign. “All Americans deserve a fair shot at pursuing higher education.”

And cost isn’t the only barrier. It can be hard to navigate the road to college—with its pit stops for the SAT, ACT, and FAFSA (that last one is the federal financial aid form, which at six pages and 153 questions is twice as long as the federal tax return). It helps to have a parent or mentor who knows the way.

Whether it’s job satisfaction, employment rates, personal earnings, or almost any other indicator of economic well-being, people with college degrees have it better. The problem is: Who can afford to get that degree?

In an exhaustive study that followed more than 1,500 low-income Chicago students for 20-plus years, researchers found the best predictors of a student’s future educational attainment included: the mother’s educational background, how many words a child learned by age six, and whether the child expected to go to college. In other words, it’s not just a matter of money or navigational skill. Things like personal expectations matter too. And that’s where NEA educators can make a difference.

“I had teachers who inspired me to go to college,” says Tabrian Joe. “And I want to inspire others to do the same.”

What Now?

There are policy solutions to the college opportunity gap: For example, the thousands of NEA members who already have signed NEA’s Degrees Not Debt pledge are asking Congress to increase Pell Grants and make federal student loans more affordable. Meanwhile, President Obama has ignited hope with a proposal to pay for two years of community college for 9 million Americans each year.

But solutions are also found in classrooms and counselor offices in any high school. Steve Schneider is a school counselor at Sheboygan South High School in Wisconsin, where about half of seniors go on to college. Many others find work in locally owned manufacturing plants — and that’s fine with him, too. But the students who concern Schneider are the ones who walk away with a diploma in hand, thinking, “What now?”

“The logistical barriers to college—the cost, the understanding the system—those are, in my mind, the easy obstacles. Because they’re factual. ‘Yes, this is what it will cost, and here are your options,’” says Schneider. “The deeper rooted obstacles, the ones that will require the whole school community, not just the school counselor, but the math teacher, the art teacher, are the obstacles that are less factual, more subjective.

“What do you do with the 9th-grader who is a less confident student? What do you do with the C-student who wanders through school, and never realizes his own potential? I can’t reach every one of those students. There’s absolutely no way I could give every one of them the one-on-one attention they need. But if I can get to 25 percent, and the English teachers get another 25 percent, and the math teachers get to another 25 percent, then collectively we can do the kind of listening we need to do with every student.”

At Sheboygan South, the counseling department requires every junior to run their own parent conference where they share their career or postsecondary plans: “what they like to do, what they hope to do,” and the work that they’ve done so far to accomplish those goals. These are empowering, says Schneider, and resemble the individualized plans required for every student in many states, from Washington to Georgia.

For Joshua Sermon, his personal plan was sparked by a YouTube video, showing the homecoming basketball game at Winston-Salem. “When I saw that, I was just like ‘that is it. That is the place for me.’ It felt like a real big family,” he says. Now that he’s part of that family, he remains motivated by thoughts of graduating and someday having his own classroom.

I believe in myself. I know I can do it,” says Sermon. “And I’ll probably have that on the wall of my classroom someday so that my students and I can read it together, and we’ll constantly remind ourselves that I can do it.”

Take the NEA’s Degrees Not Debt pledge. Stand up for college affordability alongside tens of thousands of other NEA members, students, and parents.