A faculty vote of “no-confidence” is the nuclear option on campus— the “delete your account” of academia. It says publicly, loudly, and collectively that professors no longer believe their president or other leaders can give students what they need.

A faculty vote of “no-confidence” is the nuclear option on campus— the “delete your account” of academia. It says publicly, loudly, and collectively that professors no longer believe their president or other leaders can give students what they need.

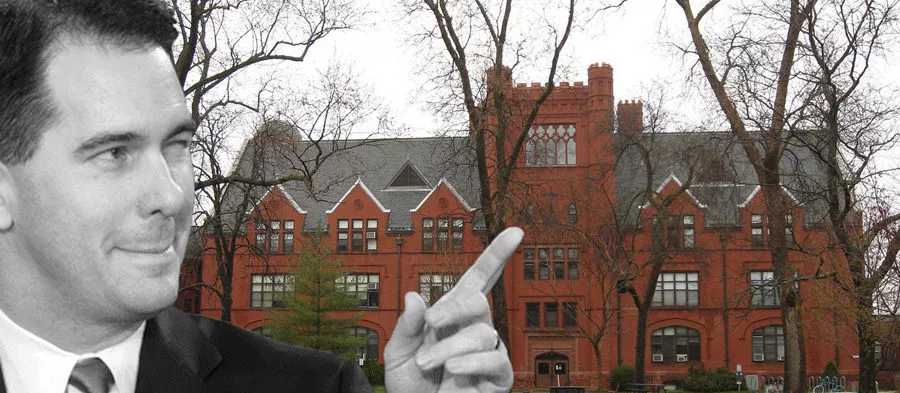

This spring, an unprecedented wave of thousands of faculty on University of Wisconsin (UW) campuses, plus the 13 two-year UW System Colleges, have voted no-confidence in UW System President Ray Cross and Board of Regents. Fed up with devastating state budget cuts, attacks on tenure and shared governance, and also what they see as the systematic demolition of one of the world’s finest public universities for political purposes, they have said enough is enough.

“By voting no confidence, we protest the intentional destruction of our internationally recognized university system,” UW-Milwaukee professor Rachel Ida Buff told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

In Milwaukee, the largest meeting of UWM faculty in decades or possibly ever—nearly 300 people—voted unanimously in May. Their vote was preceded by the initial action at UW-Madison, the system’s flagship university, and also UW-River Falls and UW-La Crosse, and then quickly followed by similar censures on other campuses. “This resolution is an expression of frustration…over what has happened to public higher education [here] over the past year, 18 months, whatever,” said Mitch Freymiller, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Senate chair, to Wisconsin Public Radio.

Meanwhile, key UW faculty members have thrown up their hands at Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker—the architect of these university “reforms”—and quit UW altogether. “At my new university in another state, I will have stronger tenure protections than I now have here. I will earn about 50 percent more than my current salary for the same job. And I will be free from the strange crazy-making double-speak that on one hand demands that higher education deliver value like a business, and on the other hand, methodically prevents it from doing so,” wrote Caroline Levine, professor and chair of the English department at UW-Madison, in The Cap Times last month.

How Did We Get Here?

In Wisconsin, public higher education is deeply rooted in UW’s 110-year-old mission, known as “The Wisconsin Idea,” which holds that the university must aim to “educate people and improve the human condition.” Last year, in a draft budget, Gov. Walker proposed striking those words about the human condition, as well as the part about the system’s “search for truth,” and replacing it with language about meeting “the state’s work-force needs.”

The mission was left unaltered after public outcry, but perhaps more troubling to its actual fulfillment was the approved budget, which cut $250 million from the UW system and froze tuition. (At the same time, Walker directed $250 million in public funds to build a new arena for the Milwaukee Bucks.) Those cuts have led to staff layoffs and unfilled faculty positions, much larger and less personalized classes, and damaging reductions to student counseling and advising services. At UW-Madison alone, officials have said they will eliminate 434 jobs, and across the system the number of employees has been reduced by more than 1,400.

It’s a false idea that students and families are served by state spending cuts and frozen tuition. As a purely economic argument against budget cuts, faculty point out that students will pay higher costs when it takes them longer, possibly six to eight years, to graduate because they can’t get the classes they need to complete their programs. Even more important, the quality of their higher education will be eroded, as faculty and staff’s “ability to educate and serve our students” is impaired, said Buff.

In addition, Walker also eliminated faculty tenure from state law last year, saying that any necessary job protections could be preserved in university policy. But this spring, when UW regents approved new policies to fill the hole left by those changes to state law, administrators were given the power to freely shutter academic programs and fire faculty for financial reasons.

UW faculty were shot down by regents when faculty suggested prioritizing educational considerations—that is the benefit of academic programs to students—when making decisions about program cuts or layoffs, as they are at peer institutions like the University of Michigan, said David Vanness, a UW-Madison associate professor and president of the UW-Madison Association of University Professors (AAUP) chapter. “Rather than defend the mission of the university, they actually welcome these new tools,” he said.

Indeed, the Regent chair wrote in an editorial: “Our new policy proposal empowers chancellors to discontinue programs as necessary for educational or financial reasons, and if absolutely necessary, it allows for faculty in those programs to be laid off. This is an important tool for chancellors and the Board of Regents.” (Meanwhile, Walker called faculty’s response a "collective groan,” and then released wrong information about faculty workload at UWM, saying that the ratio of students-to-faculty is 3:1 when it is 29:1.)

What the changes to policy mean is that faculty who do important but controversial research, say around the effectiveness of expensive pharmaceuticals, or the repercussions of repealing gun-control laws, can be much more easily silenced if they cross the wrong lawmaker or political donor. Another serious concern is that programs in the liberal arts, humanities and social sciences, where benefits to society are difficult to measure in monetary terms, will be closed and faculty laid off so that university resources can be shifted to programs where there is short-term market demand or benefits to politically connected businesses.

All of this makes it more difficult for UW to attract and retain the best teachers and researchers, notes Vanness. “We are all leaving. No joke,” tweeted former UW-Madison political scientist Sara Goldrick-Rab last summer.

“We’re seeing a lot of retirements, a lot of positions unfilled, and some very visible departures,” said Vanness. "The effects on students may not be immediately visible, but they will become apparent eventually."