The Higher Ed Funding Rollercoaster State Funding of Higher Education During Financial Crises

Key Takeaways

- Across the U.S., 32 states spent less on public colleges and universities in 2020 than in 2008, with an average decline of nearly $1,500 per student. As a result, students need to pay (and borrow) more.

- But that's not the whole problem: Institutions also are spending more on things that don't have to do with student learning, such as institutional debt. Now, state lawmakers are making plans for next year's state budgets. It's essential for faculty and staff to make their voices heard.

- Now, state lawmakers are making plans for next year's state budgets. It's essential for faculty and staff to make their voices heard.

State Funding Highlight Update

When we last visited the data in Fall 2022 for “The Higher Ed Funding Rollercoaster: State Funding of Higher Education During Financial Crises,” higher education funding by states in fiscal year 2022 (FY22) was mixed. In nominal dollars, only five states were hit with one-year funding declines; however, adjusted for the high pandemic-era inflation, 25 states’ constant dollar appropriations declined. At the time, we were hesitantly optimistic about FY23 higher education funding, as many states’ revenue streams were making strong recoveries and federal emergency funds were financially supporting colleges and universities through the COVID-19 pandemic. In the report, we shared that for FY23, “Early indicators show that funding and finance will remain a priority in state budgets, legislation, and other education policy.” But at that time, the country was facing pandemic-era high inflation, which quickly eroded many funding gains.

The analysis presented in this brief exists within the context of two important historical state funding trends:

- More than a decade of rollercoaster funding. State funding in FY08—just before the Great Recession—was at a historic high. During the recession and into the recovery years, funding levels dipped significantly but then began to recover in the years just before the pandemic. FY20 higher education appropriations were at higher levels than FY08 funding in 40 states. But, when adjusted for inflation, only 24 states saw increases in aggregate higher education appropriations. And, when measured on a per-student basis, only 18 states’ funding recovered to pre-recessionary levels. As a result, many states increased tuition to replace the loss in state funding. In FY20, although 32 states had not recovered to pre-recessionary funding levels, many were on the upswing.

- The pandemic damage. The pandemic hit in the middle of FY20, pushing states and institutions into a tailspin as most states slashed their FY21 higher education budgets. Inflation-adjusted appropriations declined in 37 states between FY20 and FY21. Only 13 states increased FY21 higher education spending, but most of these increases were small. The pandemic caused enrollments to drop; however, at the time of the Fall 2022 report, enrollment data for FY21 were not available and the resulting funding levels per student could not be computed.

Economic Milestones and Higher Education Funding

December 2007 marked the beginning of the Great Recession. States pulled back on overall spending during the 19 months of the recession, and higher education budgets were slashed in most states. Higher education spending was affected more than other spending areas because of the notion that colleges and universities can derive revenues from other sources, whereas other spending areas cannot.

Nationally, in FY08, higher education institutions received $68.9 billion for operations—or $84.4 billion in FY20 dollars—which translates to $8,823 per full-time equivalent (FTE) student. In FY09, higher education institutions experienced an average inflation-adjusted state revenue loss of $646 per FTE student for institutional operations and an additional loss of $1,078 in FY10.1 Over the same period, state spending on other higher education activities, including state-supported financial aid, also declined. In sum, inflation-adjusted state spending per student decreased in 44 states, on average more than $2,000 per FTE student, with some states’ appropriations decreasing by more than $4,000 per FTE student, in just two years.

State economies recovered during the decade following the recession, and some states increased spending on higher education. In nominal dollars, FY20 higher education appropriations were at higher levels than FY08 in 40 states, but adjusted for inflation, only 24 states saw increases in their higher education appropriations. Per student, only 18 states recovered to pre-recessionary levels and spent the same or more per FTE student in FY20 than FY08. The result? Many states increased tuition to replace the loss in state funding. This cost-shifting to students and families resulted in affordability and accessibility issues—particularly, for historically marginalized students—and created inequities.

State-by-State Trends

Large increases in inflation-adjusted appropriations per FTE student were seen in Illinois and Hawaii ($5,071 and $3,951, respectively; see Figure 1). But, of the 32 states that did not recover to pre-recessionary levels by FY20, the average inflation-adjusted decline was $1,462 per FTE student, with some states losing more than $5,000 per FTE student; for example, Louisiana spent $5,500 less per FTE student in FY20 than FY08.

Along Came COVID-19

Although 32 states’ funding had not yet recovered to pre-recessionary levels, overall higher education funding was on an upswing for the few years prior to the pandemic. Among the positive effects:

- State funding was improving in many cases, with funds earmarked to help control quickly rising tuition by restricting increases or freezing tuition levels and boosting financial aid.

- The number of full-time faculty was on an upward trajectory.

- Faculty purchasing power, which declined due to the high inflationary period during and just after the 2008 Great Recession, recovered and rose above 2008 pre-recessionary levels.

- Faculty purchasing power was, on average, about $5,000 higher in 2019–2020 than 2012– 2013—the low point—which was a 6 percent improvement.

Only 13 states increased FY21 higher education spending, but most increases were small. A few states experienced large increases, including Vermont (25 percent), Michigan (10 percent), and Washington (9 percent).

It is important to note that enrollment data for FY21 are not yet available, so

appropriations per FTE student cannot yet be computed. Given the enrollment declines that occurred during the 2020–2021 academic year, examining funding levels on a per-student basis could provide a very different picture.

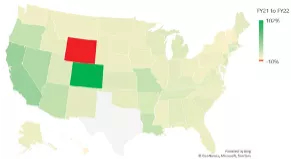

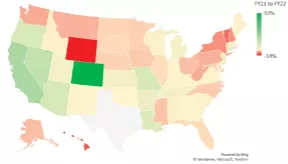

What Happened With FY22 Budgets?

FY22 budgets were a mixed bag. They were developed in late 2020 and early 2021 in the height of the pandemic and before vaccines were widely available. Some states’ budget proposals restored allocations to pre-pandemic levels or higher; however, many proposed budgets were cut during the legislative process. Even though some states’ higher education budgets returned to pre-pandemic levels, institutions were unable to keep up due to the high pandemic-era inflation.

The picture changes when dollars are adjusted for inflation. Assuming a conservative inflation rate estimate of 5 percent for FY22, more states are in the “pink zone” or “red zone,” with declining appropriations (See Figure 3b). With inflation increasing throughout FY22, the constant dollar value of state appropriations will continue to diminish. Correcting for estimated inflation, 25 states’ appropriations declined and 24 increased in FY22. (Note: Texas data was not provided in time for this analysis.)

The Future? Hesitantly Optimistic For FY23

What does the future hold for college and university funding? In most states, FY23 starts in July 2022. Many states’ revenue streams have made strong recoveries in recent months.6,7 Additionally, the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund (HEERF) financially helped colleges and universities through the pandemic even as state spending was restricted. HEERF authorized $77 billion of emergency funding for higher education institutions. For FY23, “Early indicators [from governors’ budget proposals] show that [higher education] funding and finance will remain a priority in state budgets, legislation, and other education policy.”8 But high inflation may erode funding gains.

What Are Budget Increases Funding?

While the spending targets vary by state, quite a few governors have proposed the following in FY23 budgets:

- Increased operational spending for universities

- Increased tuition assistance and financial aid

- Investments in state attainment goals

- Unprecedented funding in proposed budgets for assistance with food, housing, child care, and transportation (e.g., short-term emergency grants that would help students overcome hurdles that could force them to temporarily or permanently leave their education, like loss of child care or car trouble)

But legislatures still have their turn with the budgets, and they may cut them back in the coming months.

Will Previously Financially Restricted States Recover in FY23?

Five states experienced severe budget cuts in FY22: Wyoming, Vermont, New York, New Hampshire, and Hawaii. FY23 budget discussions in these states are a mixed bag, but they do appear to be trying to recover:

- The University of Wyoming’s proposed budget is near the requested amount, and $224 million is proposed for the seven community colleges.

- Vermont proposed $10 million of additional support to the University of Vermont and $5 million of additional support to Vermont state colleges—in both cases, to help lower tuition.

- In New York, the proposal is to increase higher education spending by $619 million, which is 8.3 percent over FY22. They also propose to hire additional full-time faculty at two- and four-year institutions, increase operating funds by reimbursing $108.4 million of “TAP Gap” tuition credits, and raise the community college funding floor.

- New Hampshire’s proposal is for both the university and community college budgets to remain steady but add $9 million for health programs, $1.5 million to support dual enrollment moves to the community colleges, and $6 million to the Governor’s Scholarship Fund.

- Hawaii’s proposed budget restores cuts to the FY22 budget, adds funding for programs in alignment with the governor’s platform regarding the labor force and funds for most capital improvements requested.

States to Watch in FY23

- Four-year institutions: $12.2 million increase

- Two-year colleges: $800,000 increase

- Technical schools: $129,000 decrease

- UC, CSU: 5 percent increase in base funding for five years

- UC: $307.3 million increase in ongoing funding; CSU: $304.1 million

- University of California’s President Drake noted, “This sustained commitment will enable UC to make critical long-term investments, particularly in areas that directly support our students.”

- Higher education: $2.2 billion; $208 million increase over FY22

- Universities/community colleges: 5 percent increase

- Grants for students: additional $122 million

- Prepaid tuition program: $230 million to pay down unpaid balance

- Operating budget for public universities: 17 percent increase, $299.5 million

- Community colleges: $349.4 million increase

- Capital improvement: $185 million for historically Black colleges and universities; $67 million for community colleges; $601 million for other projects in higher education

- State’s nursing shortage, salaries of faculty, and financial aid for students in health programs: $20 million investment

- Deferred maintenance at institutions: $183 million

- Tuition freeze support: $20 million

Although some states appear to be trying to recover and budget proposals are strong in others, other states continue to struggle to financially support their colleges and universities.

For example, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s proposal “outlined $1.3 billion for state colleges and $2.7 billion for state universities, reflecting a $100 million decrease in funding for the universities.”12 State legislatures finalized FY23 budgets in spring 2022. Future analysis of these budgets along with states’ enrollment data—while also considering the high inflation rates—will allow for identifying which states are able to strongly fund and prioritize higher education.