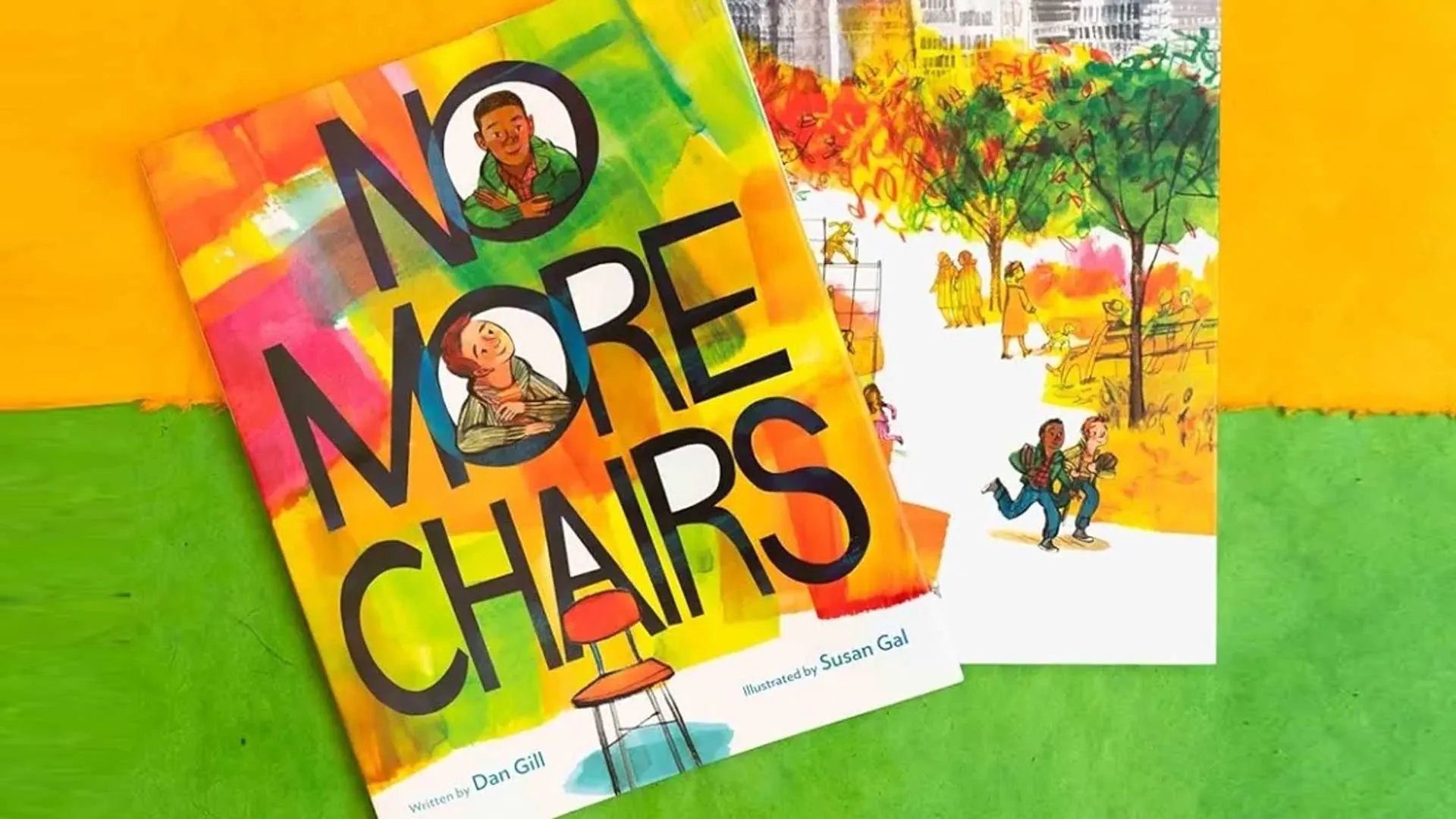

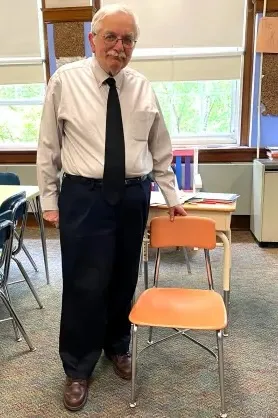

NEA-Retired member Dan Gill, who taught middle schoolers for 53 years in Montclair, New Jersey, is the author of “No More Chairs,” a new picture book featured in NEA’s Read Across America calendar for 2025 - 2026. (Check out the calendar now!) In this book, Gill explains why he kept an empty chair in his classroom for 40 years. The reason has everything to do with inclusion or, in simpler terms, with kindness.

Recently, Gill spoke with NEA Today. Here are five things to know about Gill and his new book.

The first thing to know: The story of “No More Chairs” is real.

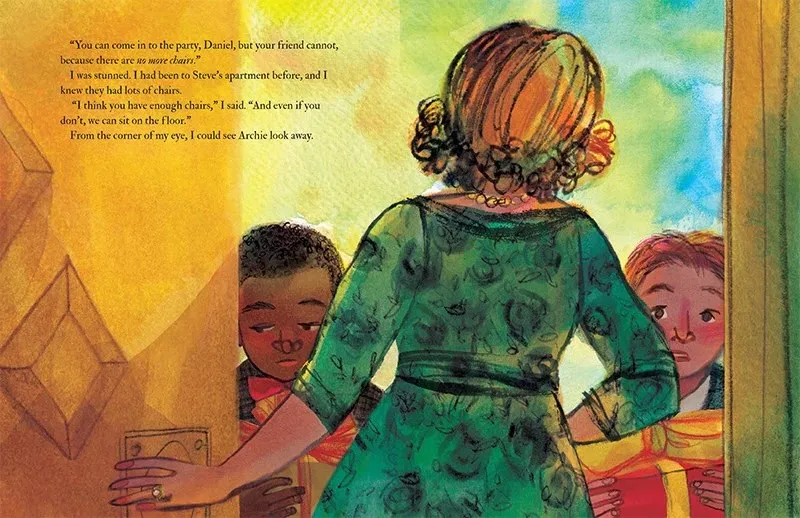

When Dan Gill was a child in New York City, he and his friend Archie put on their Sunday shoes and went off to a birthday party for a classmate. But when their friend’s mother opened the door, she looked at them, paused, and announced, “You can come in to the party, Daniel, but your friend cannot because there are no more chairs.” Her excuse was obviously fake. The real reason? Dan Gill is white and his friend Archie was Black.[1] In real life and in the book, young Dan refuses to join the party without Archie. They leave their gifts at the door and go home.

Years later, young Dan would become Mr. Gill, an award-winning social studies teacher who always has an empty chair in his classroom—and who explains why to his students. The book offers: “Because he has never forgotten how he felt that day, everyone will always feel welcome in [Gill’s] classroom. No one will say there are no more chairs. All are welcome here.”

The second thing to know: This message is more important than ever.

Just a few months ago, Idaho middle school teacher Sarah Inama resigned rather than take down a classroom poster that says, “All are welcome here.”[2] The poster was an opinion, her then-principal told her, and it violated district policy. Since the first Trump administration, at least 18 states have passed laws to prohibit “divisive concepts” in schools. Meanwhile, the White House has threatened to withhold billions of dollars in funding from districts that have diversity and equity programs.

“I want to tell her how brave she is,” says Gill, of Inama. A lot of teachers, if their principal told them to take down a poster or remove a book or whatever, might have eventually done it, he notes. “You doubt yourself. These dumb people make you doubt yourself,” Gill says. And too often, he adds, educators are alone in their classrooms: they don't know that many, many people support their efforts to welcome every child.

Since publishing the book, Gill has heard from a number of those people. “One guy sent me a piece of wood, shaped like a heart, with postage stamps on it. I didn’t even know you could put stamps on wood!” Educators from across the U.S. have invited him to speak to their mentees or appear virtually in their school libraries.

The third thing to know: Since “No More Chairs” has been selected for NEA’s Read Across America calendar, educators can access resources to use it in their classrooms

Ask your students to think about everyday objects that could serve as symbols for speaking up or ask them to choose an object that has symbolic meaning for them. Ask them to bring that object to class or take a photo of it to show their classmates. Select from among a prepared list of questions, available on NEA’s Read Across America website, to stimulate discussion or reflective writing.

As a middle school teacher, Gill often read to students. They weren’t too old—indeed, no one is too old to hear a story, he says—and it’s beneficial for students to hear “the rhythm of language.”

His favorite books for students? It was “Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes," by Eleanor Coerr. “I would read that first thing in sixth grade and then the students would teach themselves to make cranes. That was another symbol, a symbol of peace!” he says. At the end of the year, his students would send their hundreds of paper cranes to the Children’s Peace Monument in Hiroshima. Other books he favored? “Boy” by Roald Dahl: “It’s funny and it’s about kids,” he says, and also the boy-in-the-wilderness novel “Hatchet” by Gary Paulsen.

The fourth thing to know: As an educator, Gill prioritized nurturing kindness over improving test scores—and he thinks you should, too.

“I had three rules in my classroom,” recalls Gill. “Be kind. Be curious. And be on time.” The chair is a symbol of kindness, he says. Think about a child who enters a classroom midyear, not knowing any other students, maybe not even knowing the language that others are speaking. In Gill’s classroom, his middle schoolers made newcomers feel welcome. “My kids always said, ‘Come in! We have an extra chair,’ because the chair says to them, ‘Being kind is important here.’”

To other educators, Gill says: “Your school should have a symbol of how people should act toward other people and how we’re responsible to be kind. We don’t have to agree, but we have to be kind. In the national spectrum, nastiness has seemingly taken over. I’m often reminded of this Cree Indian story about how there are two wolves in each of us. One is the nasty wolf who wants to degrade people, to abuse people, to take advantage of people… The other wolf is kind, understanding, and compassionate.” When people hear about the two wolves, they always ask, “Which wolf wins?” The answer: “It’s the wolf we feed,” says Gill. “Hopefully my book feeds the good wolf.”

The other stuff that administrators might have wished Gill had prioritized—say, “workplace skills” or standardized test scores—are distractions from real learning, he says. “Administrators don’t have a lot of vision,” says Gill. In fact, it drives him crazy how much they talk about the wrong things. “The sense of curiosity is the basis of real learning, and it’s all about the teacher’s ability to create that environment in her classes. If you build a good enough education, kids will do fine on these stupid tests.”

“When you get older, you can say these things,” he adds.

The fifth thing to know: Gill thinks everyone has a story and if you want to publish yours, he’s got some advice.

Gill began telling the story of the empty chair to his students decades ago, as a way to personalize his lessons around Martin Luther King Jr. Eventually, he also began telling it at rallies and other community events.

“As a teacher, I know audiences. I know when I’m connecting and I know when I’m not connecting — and I think the way you connect is through that personal aspect, when you share something that actually happened with you,” he says. “When I would tell this story orally to people, they’d come up to me and tell them their own stories, which was my hope—it wasn’t just about me.”

Then, a few years ago, Gill and his wife were at the Montclair, N.J., book festival and saw something called “Pitchapalooza.” Twenty participants would each have 60 seconds to pitch a book idea to a panel of judges. “So, I get up and start telling my story and one of the judges starts looking at her phone and I’m like, ‘oh man, I’ve lost her,’ but what she actually was doing was googling me!” recalls Gill.

He won the contest, which paired him with an agent, who helped him get a publisher, an editor, and an illustrator. “She did an amazing job,” says Gill, of the illustrator. “She had her daughter, who lives in New York City, go the actual apartment building where this birthday party was held and take pictures for her!”

His advice: “Don’t give up. Don’t be discouraged. See if you can share your story with other people and don’t be afraid of criticism!” Support groups for writers can be helpful and often local libraries often offer them, he suggests. “Just don’t give up. You have to believe in your story.”

[1] Gill’s students often ask him what happened to Archie. “Well, we lost track of each other,” Gill would tell them. “The last time we saw each other was June 1964—and then he went to one high school and I went to another.” When the internet came along, Gill tried to find him but couldn’t. Then, a couple of years ago, when the empty-chair story started to get attention, a television producer from “CBS This Morning” asked Gill the same question. “I can’t find him!” Gill told her. A few days later, she called and said, “I have good news and bad news.” The good news was that she had found Archie. The really bad news was that he had died a year earlier of COVID. The question that Gill had for him remains unanswered. “’Do you remember this like I do?’ It obviously left an indelible mark on my brain,” Gill muses.

[2] Inama has a new job now in the Boise School District—the same district where educators bought and wore t-shirts saying, “Everyone is welcome here,” in support of Inama last spring. Her former students signed the back of her poster before she left.