Here’s a fact: In 2016, Earth reached its highest temperature on record, trouncing the record set just a year earlier in 2015, which beat the previous record set in 2014. Our planet is warming, and its temperatures are fast heading toward levels that scientists believe will threaten humans and the natural world. Another fact: Educators need to help students learn about climate change, caused by human activity. But how do we do it in a way that engages and inspires them?

1. Dive In!

1. Dive In!

The water is warm and getting warmer. “Just plunge in and teach it!” says Kottie Christie-Blick, a fifth-grade teacher from the suburbs of New York City, who joined the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA’s) Climate Stewards program in 2012 and consults on climate-change education. The topic is so important, says Christie-Blick, that no delay is defensible. “Start now,” she urges, and learn more as you move forward.

“I didn’t know much at first,” confesses Bruce Taterka, a Mendham, N.J., high school teacher. “I had to educate myself, and that’s what teachers often have to do,” he says. Over the years, Taterka has been accepted to teacher-education programs in the Ecuadorian cloud forest, the North Slope of Alaska, on a research vessel in the Gulf of Mexico, and other places where he learned firsthand the effects of climate change.

For teachers who are interested in no-cost classroom resources and professional development for teaching about climate change, many exist. (See Resources below.)

2. Use Data

2. Use Data

Climate change may be a political hot potato in some communities. (President Donald Trump called it a Chinese-made hoax a few years ago.) But the data is indisputable. “There’s really no pushback from students or parents,” says Peter Johnson, an eighth-grade science teacher in rural, conservative Minnesota, “because the measurements speak for themselves.”

For Natalie Macke, an NOAA climate steward who teaches at New Jersey’s Pascack Hills High School and her district’s virtual school, teaching about climate change is all about the numbers. Her students swim in data sets from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which include very teacher-friendly summaries, notes Taterka. They also analyze and study remote-sensing data from NASA and NOAA about pollen, fires, sea level, ocean acidity, sediment, temperatures, and more. “Be honest about what we know, what we don’t know, and what we’d like to know,” Macke recommends.

“Sometimes students will say ‘I don’t believe in climate change,’ and I’ll say, ‘it’s science, not a religion. You don’t have to ‘believe’ in it, you just have to look at the data,’” says Shannon Bartholomew, a New York state high school teacher.

Climate scientists are surprisingly accessible, and often willing to speak to students via Skype or other technology to explain their findings. In southern Maryland, Lolita Kiarpos’ high school class has plans to Skype with a Ph.D. student doing climate research in Antarctica. “Anytime there’s an opportunity to connect with something that feels real, I’ll take it,” she says.

3. Make It Local

3. Make It Local

When Shannon Bartholomew’s high-school students look out their windows at New York’s Adirondack landscape in late January, they are shocked. Why? They see grass growing on the ground. This is ski country, and the Olympic bobsled team practices nearby. “Many, many people here are employed in the business of having good winters, and that means snow,” says Bartholomew. “The kids have a huge connection to the outdoors, and they can see the changes that are happening. This is a local thing that really speaks to them.”

In another part of the country, you might be talking about the increase of extreme weather events, or rising sea levels.

Check out regional resources like the Chesapeake Bay area’s MADE-CLEAR. (MADE-CLEAR is an acronym for Maryland and Delaware Climate Change Education Assessment and Research, and it’s supported by the University System of Maryland and the National Science Foundation.) Hundreds of teachers have attended MADE-CLEAR’s workshops, in person and online, to learn about climate change, what it is and how to teach it. (A MADE-CLEAR favorite: Making model ice cores dyed with food coloring.)

At the same time, while the local angle might catch their interest, students do need to understand the global implications of climate change. This is not something that equally affects all people of the world, and it much more affects poor and indigenous people, notes Minnesota’s Johnson. Nor does your personal pollution hover over your own home. “Yes, you’re going to have local solutions, but this is a global problem and the earth is a dynamic system,” says Macke.

4. Consider Cross-Curricular Connections

4. Consider Cross-Curricular Connections

Yes, climate science is...science. (In fact, climate change is part of the Next Generation Science Standards, which were adopted in 2016 by 16 states with more to follow this year.) But the topic also provides opportunity to work more closely with your colleagues in economics, geography, communications, and other subjects. Poetry, even!

In Portland, Ore., Lincoln High School science teacher Tim Swinehart, co-author of A People’s Curriculum for the Earth, teaches a new course called “Environmental Justice and Sustainability.” In just the first few months, his students twice visited City Hall to advocate for Portland’s new ban on the construction or expansion of fossil fuel terminals, and they’re also developing a plan around their school’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Across town, Moé Yonamine at Roosevelt High has developed a role play, “We’re Not Drowning, We’re Fighting,” illustrating the impact of rising seas on Pacific islanders, which is taught in a senior inquiry class that is both social studies and language arts.

Bartholomew’s high school students have presented to the school board on the cost benefits of going solar at their high school. “They did a great job, and developed skills around communication,” she notes.

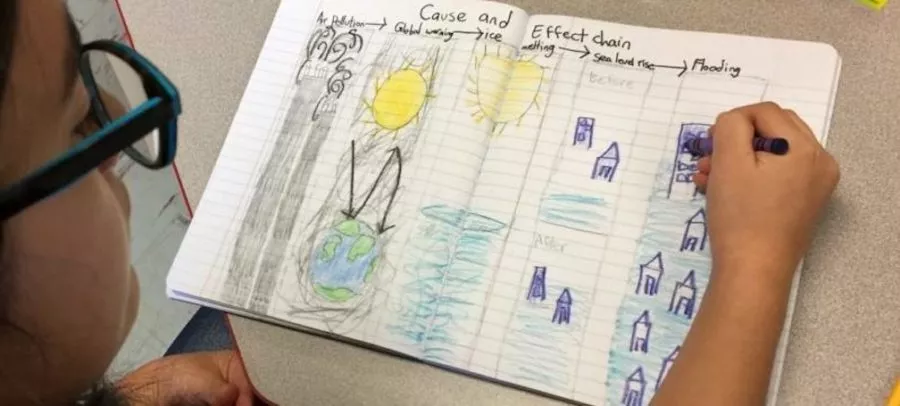

Meanwhile, Christie-Blick’s fifth graders have developed their text analysis skills through non-fiction reading on climate change. “There are also wonderful ways to connect with math, all kinds of graphs, ratios. I don’t know if you could study the science without bringing the math into it!” she says.

5. End With Inspiration

5. End With Inspiration

Dying polar bears, murderous tsunamis, and life in the Adirondacks without snow...it’s tempting to make like Rip Van Winkle and pull the covers over your head. But educators need to make clear that students can make a difference. “It’s really important for teachers to communicate that we can do something—we can act locally, and we can act at the state level,” says MADE-CLEAR’s Harcourt.

“My goal is to inspire students, not scare them to death! I stress that we can do something about this. It’s very much empowering,” says Christie-Blick. On their website, kidsagainstclimatechange.org which Christie-Blick facilitates, her students share videos on topics like “how to reduce air pollution” and “the importance of recycling.” They encourage kids around the world to join the conversation.

“There’s a lot of ‘We’re so terrible, all this horrible stuff is happening, what kind of impact can I, as a 16-year-old kid, have?’” says Bartholomew. But students are inspired to hear that on windy days Germany runs on 100 percent renewable energy. “Find the bright spots. You can’t leave them with an, ‘oh my god, we’re all going to die.’ Leave with a little positivity,” she says.

What do the Experts (Your Colleagues) Recommend?

Websites New Jersey’s Taterka recommends sticking with proven, peer-reviewed scientific resources.

At the top of his list is NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which offers a wealth of online resources and professional development opportunities, including the popular Teachers-at-Sea and Climate Stewards program.

Equally fantastic are the resources provided by NASA . “What’s interesting about going to NASA’s climate change hub is that the rate of sea level rise is higher every time I do it!” says Minnesota’s Johnson. “It was 2 millimeters a few years ago, then 3, and now it’s 4. It speaks for itself.”

Also worth checking out are the National Center for Science Education, the National Science Teachers Association, and one of Macke’s favorites: the CLEAN (Climate Literacy and Energy Awareness) Network. It’s searchable by grade and content, she notes.

Videos Maryland’s Kiarpos opts for “Climate Change 101 with Bill Nye” for an easily understood, 4-minute film.

New York’s Bartholomew says her students were deeply motivated by Leonardo DiCaprio’s 2016 95-minute documentary, “Before the Flood,” which travels from Greenland to India to examine climate change. For a limited time, you can watch it free here.

Games and Activities “How big is your carbon footprint?” To find an answer, students reveal how they get to school, how many airplane flights they take annually, how they heat their homes, etc. It definitely brings the science home, says Bartholomew.