Cara Bryant knew things were deteriorating at the virtual charter school where she taught, but it took an offhand remark by her 4-year-old son to put it into focus. During a conversation one afternoon with a fellow parent, Bryant mentioned that she was a teacher. Overhearing the exchange, her son looked up, laughed and said, “Mom, you don’t teach. Dad teaches.”

Bryant was startled but she knew he was right. Her husband was a classroom teacher at a local high school. But what she had been doing at California Virtual Academies (CAVA) didn’t really seem to qualify – or at least not any longer.

A former public school classroom teacher, Bryant took the job with CAVA – a network of 11 virtual charter schools owned by K12 Inc., the nation’s largest for-profit charter management corporation - in 2006. As she and her husband started a family, Bryant was attracted to the flexibility of working from her home in Davis and be a part of something that seemed new, exciting and challenging.

“When I began teaching at CAVA I taught biology and physical science and had no more than 150 students,” Bryant recalls. “I spent all my time on instruction and academic support for the students, helping them with questions, holding weekly live sessions. I was a teacher.”

After a few years, however, support positions began to diminish, burdening the teaching staff with a load of administrative paperwork. Soaring enrollments added more students to Bryant’s and her colleagues’ classes.

“Many students were falling through the cracks. The teachers were reduced to being paper-pushers. We don’t know our students the way we used to. We couldn’t reach out to them the way we used to. The situation was just untenable.”

California Virtual Academies, a network of online charter schools, graduated only 36 percent of tis students from 2010-13.

California Virtual Academies, a network of online charter schools, graduated only 36 percent of tis students from 2010-13.

Bryant and her colleagues decided to take action. They banded together and began an organizing effort to give the teachers employed by CAVA a voice and to steer the schools in a new direction. In 2014, they voted to become the first K12 Inc. operation to unionize.

The 750 CAVA teachers are just a few of the educators across the country who are speaking up and demanding more charter school accountability - not to undermine or dismantle charters but to safeguard and protect the interests of students, parents and communities the schools are supposed to be serving.

“What we want is to shift the focus to what’s best for the students, “ says Bryant. “Right now the interests lie too much with the shareholders. That is clearly not what education in this country should be about. “

A 'Movement' Gone Rogue

There’s no denying the dramatic growth of charter schools - taxpayer-funded but privately-managed schools that are exempt from some of the rules governing traditional public schools. During the 2007-08, 1.3 million students attended 4,300 charters. By the 2013-14 school year, those numbers had shot up to 2.57 million students in 6,440 schools. In 2015, 600 new schools opened their doors.

Impressive numbers, but it wasn't all roses and sunshine for the charter sector in 2014, as the usually deferential news media turned up the scrutiny. We began to read and hear less about “innovation,” “freedom,” “choice” and “visionaries” and more about “corruption” “mismanagement”, “graft,” and “waste.”

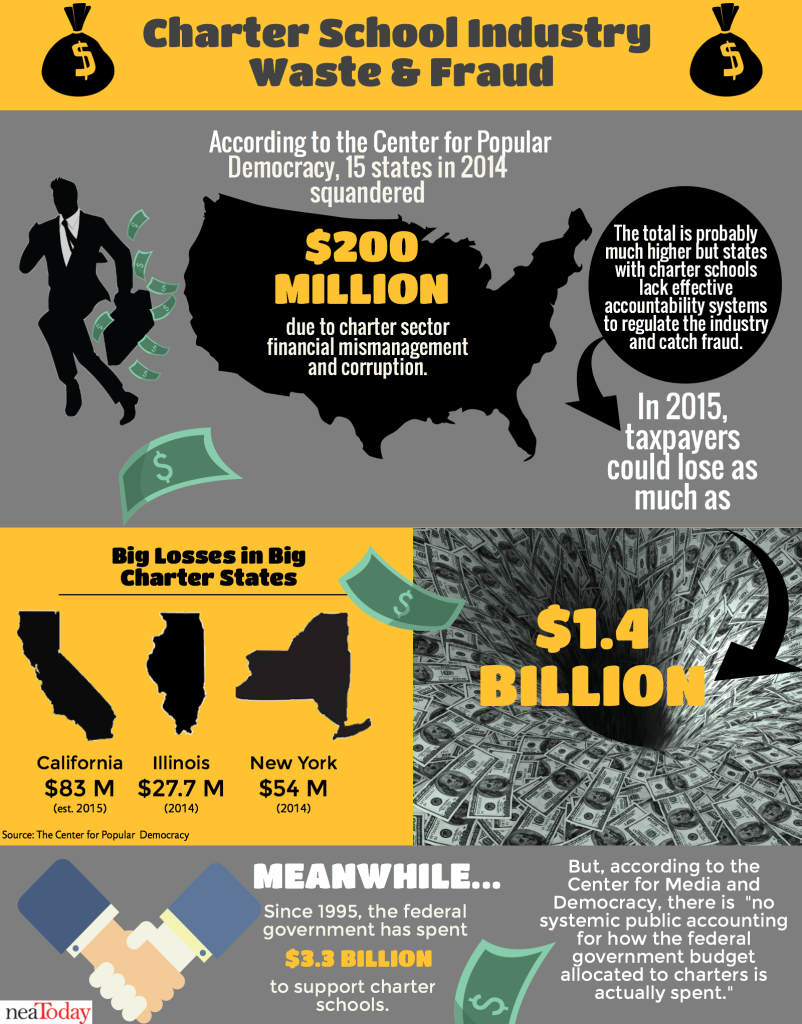

Some charter advocates may dismiss reports of malfeasance as the shenanigans of a few bad actors, but the Center for Popular Democracy (CPD) exposed the massive scale of the sector’s shoddy practices in a series of startling reports. In April, CPD revealed at least $200 million in 15 states had been squandered or misused through various activities - everything from the use of taxpayer funds to support other businesses to outright embezzlement. That total is probably higher, but, according to the report, it’s difficult to pinpont “because the federal government, the states, and local charter authorizers lack the oversight necessary to detect the fraud.”

The audacity of these operators, says NEA President Lily Eskelsen García, is astonishing.

“If charters are to continue receiving public funds, they should be accountable to the public — the very communities they exist in. But more and more we see the voices of educators, parents and community members bypassed in favor of doing what’s best for corporate profits—and students end up truly paying the cost,” García said.

CAVA, for example, graduated only 36 percent of its students from 2010 to 2013, according to a report by In The Public Interest. At the same time, the company aggressively expanded its operations and funneled a sizable chunk of revenue into advertising, executive salaries and profit.

“Instead of providing students and educators with the resources they need,” said Bryant, “K12 Inc. has been sending a huge amount of its state funding to corporate headquarters in Virginia. Taxpayer dollars are not staying in the classroom.”

And yet, despite the bad press, the charter sector is expanding. New communities with low-performing schools are being targeted, too many gullible/complicit politicians willingly rubberstamp any and all applications and too many federal policymakers support the creation of more charter schools even though money previously spent on new charter creation is not properly accounted for, or accounted for at all.

And charter schools continue to enjoy a fairly strong level of support from the public, more a reflection of a general approval of the idea behind the schools, not of the activities of many for-profit operators and the lack of accountability.

That’s an important distinction says Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation in Washington D.C., and co-author (with Halley Potter) of “A Smarter Charter: Finding What Works for Charter Schools and Public Education.”

“If charter school advocates really want to make an impact in a positive way, if they want these schools to thrive, they are going to have to change their direction."

Kahlenberg believes that, despite rampant failure in the sector, the right kind of charter schools are worth preserving and emulating.

It’s important to understand, Kahlenberg says, that it was the legendary Albert Shanker, longtime president of the American Federation of Teachers, who first articulated the vision for charter schools in the late 1980s.

“What Shanker was talking about was not this competitive model we have today, but a collaborative approach between charters and traditional public schools,” Kahlenberg explains. “He envisioned a place that taught students from different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds and where teachers had the opportunity to experiment with pedagogical approaches. These lessons would then be used to help education for all children in traditional public schools.”

So what happened? Conservatives – soon joined by many on the left – hijacked the idea in the 1990s and turned Shanker’s vision inside out. Soon a “movement” morphed into an “industry.” Instead of a system that empowers educators and students, we now have a system that empowers management. Instead of more integration, many schools are even more racially and economically segregated than traditional district schools. And charters have spurned collaboration, instead becoming part of the competition, spending far higher proportions of their funds on administrative overhead expenses, including marketing, than do traditional district and magnet schools.

“If charter school advocates really want to make an impact in a positive way, if they want these schools to thrive, they are going to have to change their direction,” Kahlenberg insists. “The current model is simply not sustainable.”

What Makes a Charter Smarter?

Ohio is home to roughly 400 charter schools, largely clustered in the state’s big cities, including Columbus, where Franklinton Preparatory School opened its doors in 2013. A small start-up, Franklinton serves about 150 students and is staffed by 10 educators.

Ryan Marchese, a technology teacher at Franklinton, says the school values the teacher-student relationship and educators were excited to be a part of a new start-up. Still, Marchese and his colleagues believed that the school’s success could be more assured if the educators had a greater voice. In March, the staff voted to join the Ohio Education Association to become the first start-up charter in the state to unionize under the National Labor Relations Board.

Ryan Marchese (third from right) and his colleagues outside Franklinton Prepatory in Columbus after they voted to join the Ohio Education Association. Photo: Ohio Education Association

Ryan Marchese (third from right) and his colleagues outside Franklinton Prepatory in Columbus after they voted to join the Ohio Education Association. Photo: Ohio Education Association

“All we want is a role in the direction of the school,” Marchese says. “We’re the ones in the classroom. We know the students the best and we have something to offer. Everybody wants Franklinton to do the best it can for its students and their families.”

The leadership at Franklinton opposed the move and immediately tried to obstruct the vote, a familiar and counterproductive posture of charter management, says Kahlenberg. “This animosity toward unions and teacher leadership hasn’t served most charter schools well.”

One look at Ohio’s charter record – according to the 2013 state report card, charter schools in in the state performed far worse than traditional districts – and its easy to understand what compelled Marchese and his colleagues to push for a more collaborative relationship with management.

Along with racial and socioeconomic diversity, teacher voice is one of the two pillars of the “smarter charter” Kahlenberg and Potter discuss in their book.

“Teachers should be shaping curriculum, they should be on committees to hire new teachers. These are basic issues of workplace democracy,” explains Kahlenberg.

When Steve Barr founded the Green Dot Middle and High school charter schools in 1999, an acrimonious relationship between staff and management was a pitfall he sought to avoid. From their beginning, Green Dot schools – there are currently 22 scattered across California – have always had unionized staffs. Green Dot is one of the handful of charter school profiled in “A Smarter Charter” as potential models.

Educators at Green Dot charter schools have always had a strong voice in curriculum, budget and other major school issues. Photo: Green Dot Schools

Educators at Green Dot charter schools have always had a strong voice in curriculum, budget and other major school issues. Photo: Green Dot Schools

Salina Joiner, the president of Asociacion de Maestros Unidos, Green Dot’s teacher union (affiliated with the California Teachers Association) says the teacher’s contract clearly stipulates a strong and constant role for teachers in the decision-making process.

“Our members have a right to question polices and decisions, and when problems arise the union and management will work collaboratively to solve them,” explains Joiner. “Teachers have input on curriculum, professional development, budget, and other important school site decisions."

Even where this collaborative arrangement does not exist (it is still very much an outlier, Kahlenberg concedes), educators and parents are still demanding better from the charters in their state. Inside Tennessee’s 80 charter schools, for example, teacher voice is absent, but lawmakers are discovering that voices outside the system can be just as vocal and persuasive.

Pushing Charter School Accountability into the Spotlight

A 2015 survey conducted by GBA Strategies revealed that nearly 80 percent of voters in Tennessee believe charter schools should not harm local public schools and should be held to the same level of accountability.

In a state where charters have quickly proliferated in the urban centers, the call for more stringent review is long overdue. In 2011 and 2012, Tennessee lawmakers avidly rewrote charter laws to create the friendliest environments possible for out-of-state operators to roll into struggling districts and set up shop.

In their organizing campaign, educators at California Virtual Academies reached out to parents and other community members.

In their organizing campaign, educators at California Virtual Academies reached out to parents and other community members.

Citing fiscal recklessness, disruption to communities, and growing racial isolation of many charter students, the school board in Nashville began to push back, aided by an increasingly vocal army of educators, parents and community members fed up seeing their neighborhood school being turned over to for-profit charter operators.

In May, the Metropolitan Nashville Education Association (MNEA) led its members in a campaign to persuade the board to approve a resolution to support independent accountability and transparency standards developed by Brown University’s Annenberg Institute for School Reform. Promoted by the NEA, the standards include transparent school governance, collaboration between traditional school districts and charter schools, and equal access to all interested students. The resolution called for these standards to be applied to all decisions over charter expansion.

“We mobilized union members, other educators, parents, and community members to raise awareness of the standards and then moved them to take action to adopt them through a resolution,” recalls MNEA President-Elect Erick Huth. “We used an email campaign, op-eds, other media efforts, testified at school board meetings and lobbied school board members direct. Ultimately, we had a fairly broad coalition of parent and community partners who helped us in this effort, which was key to its success.”

These partnerships are likely to only grow as malpractice in the charter sector gains wider notoriety and educator organizing is seen as a channel to help create stronger schools for every student. The road hasn't been easy. The organizing campaigns at Franklinton in Ohio and CAVA in California have persevered through the countless obstacles that have been thrown in their way.

“This isn’t just about our individual school,” Ryan Marchese says. “This is a movement to bring accountability to charter schools and the best education we can to our students. They’re the same things. A stronger teacher voice is in everybody’s interest.”