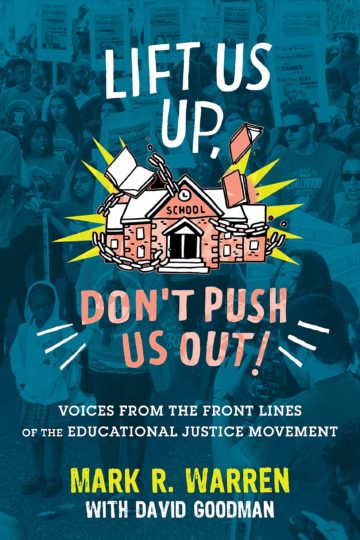

A young girl handcuffed to a pole at a police station for the crime of doodling on her desk or a boy dragged by his collar through the mud and back through the school entrance before he could explain that his IEP allowed him to be outside are outrageous examples of institutional racism we don’t often hear about but that happen in our schools with alarming frequency. The new book Lift Us Up, Don’t Push Us Out: Voices from the Front Lines of the Educational Justice Movement, features voices of a new movement for educational justice. Each essayist tells the story of how black and brown parents, students, educators, and their allies are fighting back against profound and systemic inequities and mistreatment of children of color in low-income communities.

A young girl handcuffed to a pole at a police station for the crime of doodling on her desk or a boy dragged by his collar through the mud and back through the school entrance before he could explain that his IEP allowed him to be outside are outrageous examples of institutional racism we don’t often hear about but that happen in our schools with alarming frequency. The new book Lift Us Up, Don’t Push Us Out: Voices from the Front Lines of the Educational Justice Movement, features voices of a new movement for educational justice. Each essayist tells the story of how black and brown parents, students, educators, and their allies are fighting back against profound and systemic inequities and mistreatment of children of color in low-income communities.

NEA Today spoke to one of the contributors, Zakiya Sankara-Jabar, who writes about how her African American son was pushed out of preschool. She is National Field Organizer for the Dignity in Schools Campaign and she co-founded Racial Justice NOW! to provide a voice for parents facing racism in schools. Within a few years they won a moratorium on pre-K suspensions in Dayton schools. We also spoke with Lift Us Up co-author Mark Warren, a professor of public policy and public affairs at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Warren studies and works with community and youth organizing groups seeking to promote equity and justice in education, community development, and American democratic life.

How did you become involved in the educational justice movement?

Zakiya Sankara-Jabar: I came into the work as a parent pushing back on the treatment of my then three-year-old son who’d been labeled as a problem and a disruptive student. They used words that I thought were typical of three-year-olds, like temper tantrum or trouble transitioning. I wasn’t thinking about it at the time as a racial justice issue or what the stereotypes around me might have been. They’d ask me if there were problems at home, and I was a working class black mother, and I sort of internalized what was being projected on me and my family.

I was actually a part time employee for the state of Ohio and also a full-time graduate student. That child care facility was on the campus and it had an excellent reputation. But the preschool is very expensive – $1000 a month – and I qualified for title 120, a welfare program that allowed children to attend the preschool for free if their parent is working at or attending the school. When I signed up for the voucher I was treated brusquely and the woman said, “You know, we only accept so many of these.”

And then, my very bright, energetic, and normal three-year-old who loved going to preschool was starting to have emergency removals where they’d call me and ask me to pick him up for what I know realize are minor issues typical of energetic kids. I started to see his little bright light starting to dim. Before they expelled him, I removed him because I didn’t want that to be his experience. He’d tell me, “Mommy, I don’t think my teachers like me.” At only three years old and already feel you’re not wanted! I then co-founded Racial Justice NOW!

Why aren’t more people aware of institutional racism and the biases experienced by students of color?

Why aren’t more people aware of institutional racism and the biases experienced by students of color?

Mark Warren: A lot families of color are aware, but for a white person who interacts mostly with white communities, the reality is that they’re really unaware of what’s happening in communities of color. There are two Americas. People are shocked when they hear these stories. But because of the segregation that still exists, these stories aren’t well known.

The point of the book is to bring these experiences out into the wider world, not just to expose the individual biases but how these practices are systematic in our schools with harsh zero tolerance policies, and also the strong and pervasive inequities with schools that are under-resourced with less-qualified teachers and wider issues of poverty.

Can you describe the educational justice movement and how it began?

MW: Families and communities have been struggling historically for a long time. You can go back to the struggle of slaves fighting for the right to read. We’re in a new phase of that movement and that was the occasion for this book – to tell the stories of change led by parents, students, educators and their allies in this movement. Organizing groups like Racial Justice NOW! in Dayton, Ohio, were really struggling on their own and were isolated in local communities. Over the last several years they have found ways to come together and connect.

Through the Dignity in Schools Campaign, the Journey for Justice, and other national alliances, local groups are joining with other organizations around the country in an educational justice movement. Now they’re not fighting on their own and local groups have the resources and support from national alliances.

Why are parents critical to the movement and creating change?

Zakiya Sankara Jabar

Zakiya Sankara Jabar

ZS: One thing I found out in the process is that parents of color have been socialized to believe that they have no power, and it’s even more pronounced if you are a black mother who is poor or working class. There is a lack of respect and dehumanization. I say that from experience – personally and as an advocate. We have to work hard to change the narrative of how they see working class parents and how they pathologize us. There is an ecosystem and we must realize that if a child has some needs, he has a parent with some needs.

We talk about this as a social justice crisis and systemic discrimination and poverty. These crises are always addressed and changed by the people most impacted by the inequities. Movements built and led by people most affected are the most effective, like the Civil Rights movement. We won’t have an education justice movement unless parents and students are at the heart of it.

What other groups are integral to the movement?

MW: Alliances are critical. Labor unions, service workers unions, hotel workers unions -- where are their children going to school? They’re going to underfunded, low-income urban schools. In Los Angeles, the janitors union negotiated for parent advocacy workshops as part of their contract so they could be advocates for their children in the schools. This is how you bring about systemic change. They also negotiated for time off in the contract so they can go to meetings at schools during work hours.

What role do educators play?

MW: If we want to transform schools, educators have to be part of the movement. Teachers in low-income schools with no resources, teaching in old, decaying buildings and in districts that are dysfunctional – they need to be a part of this, but it isn’t an add-on for them. They teach in the first place to help children and advocate for them. They can’t do that until they help change the policies, like ending the overuse of tests that prevents them from teaching real content and building relationships with students.

In the book, we show how educators can find ways to partner with their students, families, and communities to change the way resources are being used. They can find ways to introduce restorative justice and improve school climate for all students. This isn’t an add-on or an extra. This needs to be work they’re doing to fully educate children.

It’s also true that some teachers have to take a hard look at their own practices and examine personal issues of bias and stereotyping. Are they participating in practices that are pushing students out? We want to be there to support teachers trying to change and this book can help.

How do we change mindsets about different groups of students? In one essay a girl writes about being labeled “ghetto” — why are some students labeled in such a way?

ZS: That student’s experience with being labeled ghetto because of the way she dresses or acts is in accordance with middle class culture and vividly shows the gap between many teachers and the communities they serve.

Things can change when young people themselves stand up and become part of the organizing processes and challenge these mindsets. The students can demand that they be treated with respect. There are lots of students who look like, or even say, they don’t care and who have discipline problems, but as individual people they have tremendous potential and ideas just like every person does.

They need the resources that more affluent girls have to be given chances to realize their potential. In our two-tiered education system, some kids go to modern, resourced schools where students are respected and valued, while others go to schools where the ceilings are caving in and their bathrooms are broken and they’re subjected to harsh discipline.

What are some key elements to a just educational system?

MW: There are lot of elements, but equity is at the top. We must offer the same quality of education to all of our children. Educational systems in low-income communities will need more resources at the start because they have been systematically underfunded for years. Other elements include strong relationships between teachers, students, and families; the removal of racial stereotyping; culturally relevant education; and a curriculum that builds upon African American and Latino cultures rather than solely on white Europeans. Finally, a just educational system empowers our students, allowing them not just to answer questions, but to ask them. Asking questions allows them to become agents of change.

What do you hope will be the impact of this book?

ZS: I hope that this book is shared widely and that it helps shift the narrative about communities that are over-criminalized and seen as deficient. That it shifts the narrative about what it means for black and brown children to be educated. That they have the access to an education that is appropriate, culturally relevant, and not be pathologized for being uniquely who they are.

MW: I hope the book will inspire people to take action. I also hope the book helps people understand that to really create the kind of change we need, it isn’t going to happen by tweaking one thing or another. There is a profound question of social justice across the country, not just in education. We hope this movement sparks a resurgent social justice movement with education at the heart of it. Education is a critical institution for democracy. What will be the future of our black and brown children? Will they be fodder for prisons? Cogs in a capitalist society? Or will they be agents of change and social justice warriors for the future?