Key Takeaways

- According to scientific research, the effects of sleep deprivation in teenagers are severe, and starting school later would be a big step forward in reversing this trend.

- In 2019, California became the first state to mandate later school start times for all middle and high schools. Florida followed suit in 2023, but repealed the law in 2025.

- Although schools can and should help adolescents get more sleep, experts, including many educators, caution that later school start times aren't a cure-all—and could present logistical and budgetary headaches.

8 - 10

8:30

In 2023, Florida became the second state in the country, after California, to mandate later school start times. The law instructed every school district to implement a new schedule with start times no earlier than 8 a.m. for middle schools and 8:30 a.m. for high schools. The move was likely to affect more than 2 million of the state’s public school students and their families.

These two states—along with many districts across the country with similar policies—were responding to a growing body of research showing the benefits of more sleep for teenagers.

In May 2025, however, Florida stepped on the brakes. Lawmakers repealed the policy before it even took effect. And no other states have approved legislation mandating later start times. Are the science and research wrong? Unlikely. Is the idea of later school start times a bad idea? Probably not. But that is not what is really behind the misgivings.

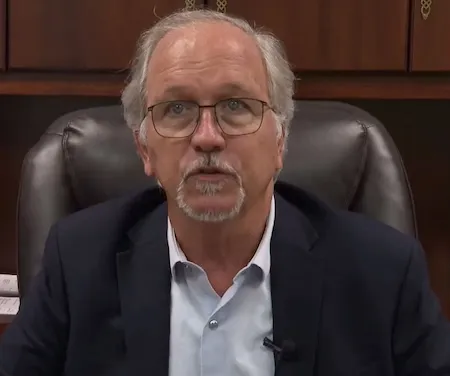

The issue, says Gordan Longhofer, president of the Palm Beach County Classroom Teachers Association (CTA), was that the mandate would have likely led to chaos.

“I don’t think many people understood the complexities involved in changing school schedules,” Longhofer explains. “Such an undertaking should be designed at the local level—with the input of educators and others who know the community, the needs, and feasibility. These are the stakeholders. They should make this decision, not a lawmaker 400 miles away, saying ‘do this or else.’”

Teenagers Need More Sleep

The campaign to start school later began in earnest in 2014, soon after the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued findings that laid out a stark and sobering picture of how sleep deprivation harms students, especially high schoolers.

The research revealed that adolescents who don’t get enough sleep have an increased risk of being overweight, suffering from depression, and struggling academically. According to most surveys, the average teenager logs about 7–8 hours of sleep each night, when they should be getting somewhere between 8-10 hours.

That same year, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended that middle schools and high schools delay the start of class from an average start time of 8:00 am to 8:30 a.m. or later to align with the biological sleep rhythms of adolescents.

“Chronic sleep loss in children and adolescents is one of the most common—and easily fixable—public health issues in the U.S. today,” said Dr. Judith Owens, author of the AAP policy statement.

The idea has grown in popularity over the past decade as student wellness has become a front-and-center issue, particularly in the wake of the pandemic. Recent research has only solidified the consensus that teenagers are sleep deprived and, furthermore, school schedules are putting them at a greater disadvantage.

Do Later Start Times Help Students?

No question, sleep deprivation among teenagers is a serious issue, says Joseph Buckhalt, a professor at Auburn University, in Alabama, who conducts research on sleep, health, and adolescents. But the impact of later school start times is being a bit overhyped, he cautions.

“One caveat is that we haven’t really waited long enough to see if there’s really a positive effect,” Buckhalt explains. “Are teenagers really sleeping longer due to later start times? Or are they just staying up longer? Also, there are many other barriers to getting good sleep that might overcome the benefits of a later start time.”

Those challenges affect lower-income families disproportionately, he says. Buckhalt co-wrote a 2022 study that looked at the health benefits of later school start times among different socioeconomic groups. They found that only higher-income students had fewer depression symptoms from later start times.

For other families, pressures such as financial insecurity, long commutes, and other challenges essentially negated any benefits from a new start time.

Buckhalt says no one should view later school start times as some sort of cure-all. There are, after all, other variables that contribute to sleep deprivation in adolescents—homework, too many extracurriculars, and, of course, the infamous "blue light" emitted from electronic screens as teens text and scroll through social media.

Still, early school start times are not in sync with changing circadian rhythms. As students enter their teenage years, their internal clock moves to a different schedule, making them feel sleepy later at night. “Teens are biologically wired to fall asleep later and wake up later,” Behavioral and Social Scientist Wendy Troxel wrote in a column for the Rand Corporation. “Early school start times virtually guarantee chronic sleep deprivation among teens, and the consequences are significant.”

A Domino Effect

Despite the consensus around teenage sleep and health, the momentum behind later start times seems to have stalled. Buckhalt calls the state mandates “coercive,” and believes advocates for the policies have erred by not involving education professionals and other stakeholders. In some cases, he says, they have also lacked transparency in the decision-making process.

When Florida lawmakers passed their state law, the Palm Beach County CTA immediately began working with the local superintendent and school board about implementation in county schools.

“We reached out to the district office and said we want to be a part of the discussions about any of these plans going forward,” Longhofer recalls. “It was going to literally be a math problem. You’re talking about the schedules of 180,000 students in state-funded schools [and] getting the times worked out so that kids get to school on time, and people can have some semblance of a reasonable workday—whether they’re teachers or parents. This was going to be a monumental task. Everyone was worried about the impact.”

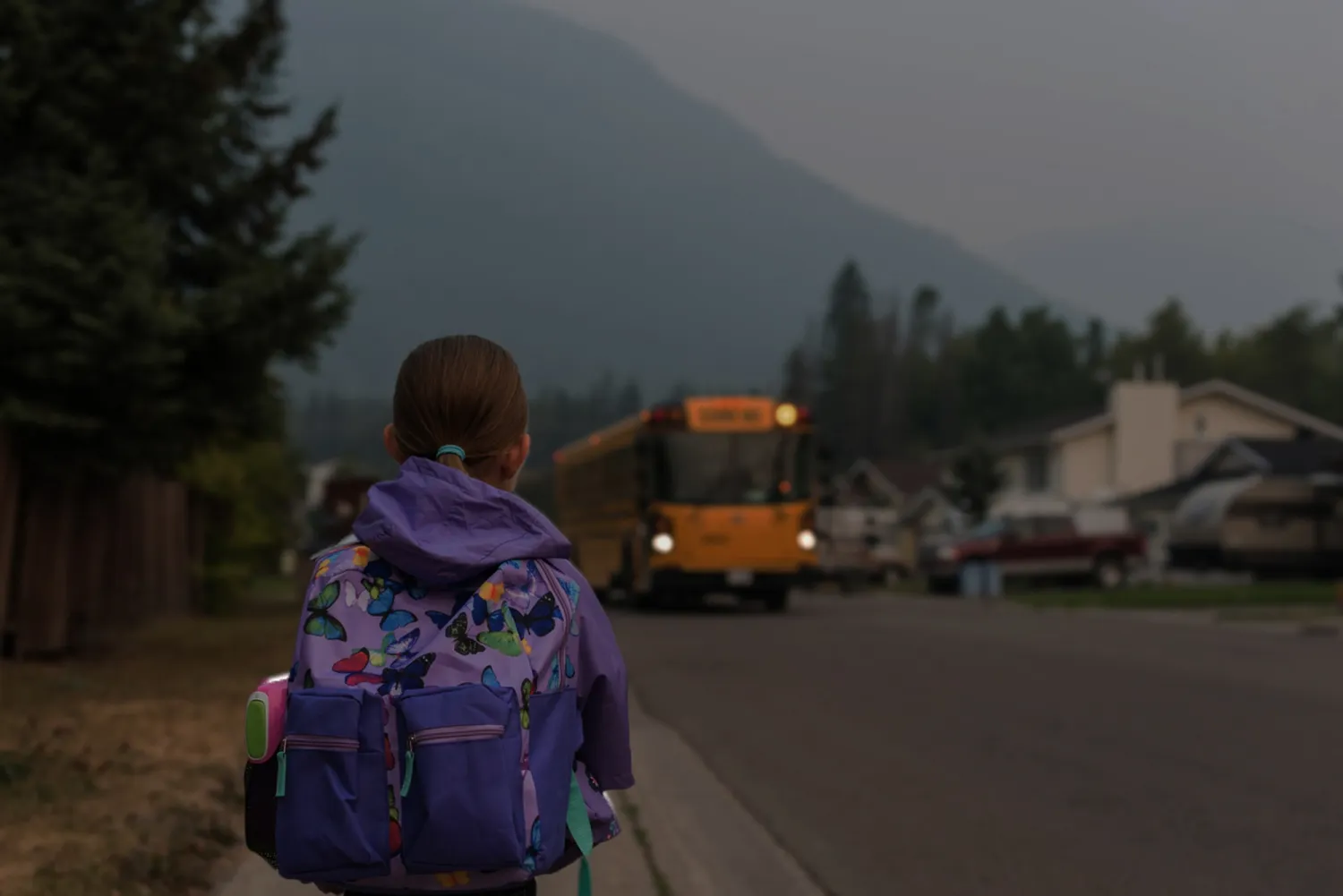

The same challenge faces every school district that has shifted schedules later, and it’s especially complicated for larger districts. A shift of 30 minutes or even an hour later means that students will finish their day later than 3 p.m. That triggers a domino effect for everything from after-school activities and programs, parents’ work schedules, childcare arrangements, and after-school jobs.

Then there’s the bus routes.

For later school start times to work, districts usually have to remap bus routes and hire more drivers—even as they face existing driver shortages. Some districts implemented multiple new start times without enough new routes and drivers, causing many students to miss significant amounts of class time because buses couldn’t get kids to school or home on time.

‘Are We Really Thinking This Through?’

Many districts that have changed start times have flipped bus schedules, so elementary schools now start the earliest.

“The thinking is that since sleep deprivation is an issue for older students, the [younger] children can handle starting school much earlier and free up bus routes in the process,” Buckhalt explains. So far, studies have shown that these earlier start times have not had a discernible negative impact on elementary students.

But for Zach Fisher, a special education teacher in Louisville, Ky., many lawmakers are not properly weighing the disruptions of such a move. “Are we really thinking this through?” he asks.

Fisher says moving back the start times of elementary schools could hurt families at Churchill Park School, where he teaches. “We have a lot of working-class families, immigrant families. A lot of our parents are already financially strained and cannot find more day care if our elementary students start school early and therefore leave earlier,” Fisher explains. “That opens a wider window in which they are unsupervised. Where are they supposed to go?”

Fisher also points out that lower-income parents often don’t have the option to adjust work schedules to accommodate the new start times.

A Complex Issue

The Florida legislature’s repeal of the state law in May (a move supported by the Florida Education Association), gave Palm Beach County and other large districts a reprieve from grappling with the costs and logistics of new start times in 2026. “We once again have the flexibility, the local control, to address the issue,” Longhofer says.

Like Palm Beach County CTA members, educator unions across the country have expressed concerns about these policies, tackling the issue through legislative action and collective bargaining.

The message is the same: Sleep deprivation among teenagers is a serious issue, and later school start times may be an answer, but the voices of educators and parents must be heard.

“This is a complex issue with a lot of moving parts,” Buckhalt says. “However lawmakers and districts choose to address it, you have to get everyone on board.”

Fisher believes in using research to support sound policies but says lawmakers and the public need to understand the “real life … consequences they may not know or care about. But it’s our job to help make sure they are aware.”