Key Takeaways

- Around 1,000 Austin teachers worked from home this fall because of health conditions that put them at high risk of complication or death from COVID-19.

- They include educators like Caroline Sweet, a literacy coach who is recovering from cancer surgery and chemotherapy, and whose immune system is very vulnerable to viruses.

- Last month, the district told them to go back into school buildings. After sustained outcry by educators and parents, the district helped hundreds of those high-risk educators get vaccinated first.

A few weeks ago, on a Friday afternoon, Texas teacher Carmela Valdez got a surprising email about the sudden availability of COVID-19 vaccine for a group of high-risk Austin teachers. At 7:45 a.m., the next morning, she got the first shot.

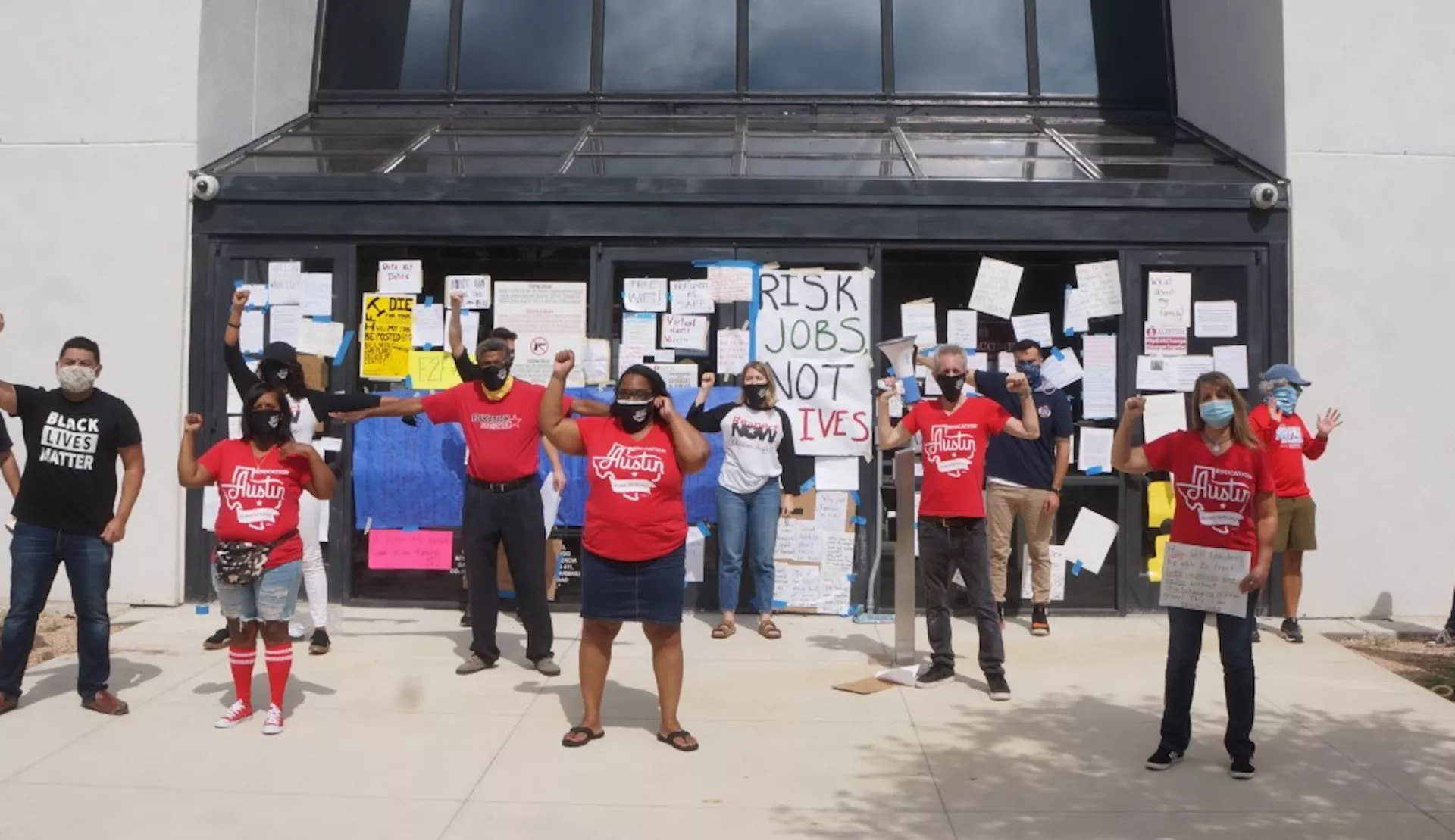

It seemed fast—just hours between email and injection—but the road to vaccination for those high-risk educators actually had been many months in the making, and involved purposeful and persistent union-led activity: coordinated emails and “speak outs” at school board meetings, noisy car caravans and heartfelt signs taped to school district offices. The message was this: Keep educators safe. Keep students and parents safe.

“I love my union! If we had not pushed, I am certain we would not have gotten what we got,” says Valdez. “Without a union, people can treat you however they want. Together, we are stronger. And I really feel like we were stronger together, in the face of this pandemic.”

Safety First

From the beginning of the pandemic, Education Austin—alongside NEA and unions across the nation—have been pushing for health and safety measures to protect students, parents and educators from the pandemic. This fall, the union also asked the district to approve telework arrangements for educators at high risk of complications or death from COVID-19. As a result, in September, about 1,000 Austin educators received medical accommodations.

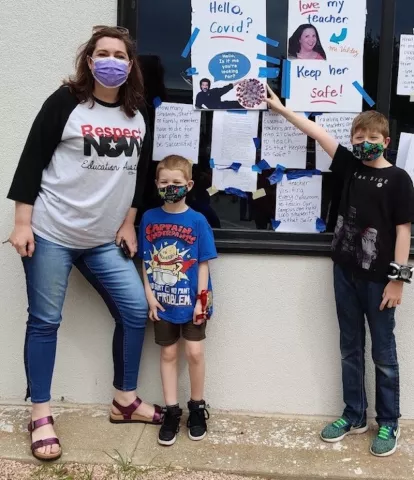

Among them were Caroline Sweet, an Austin literacy coach whose doctors diagnosed her last spring, at age 38, with Stage III colon cancer and removed a baseball-sized tumor from her abdomen. Through September, Sweet endured chemotherapy, which, in combination with the surgery, hopefully has eradicated the cancer. But she remains immunocompromised, as her doctors have attested, and very vulnerable to viruses and infections. Her two sons, ages 6 and 11, are learning from home and will continue to do so for the school year.

“I know virtual learning is not ideal. I miss field trips, and watching kids as they read, write and create, and just our overall shared experiences,” says Sweet, who has been teaching 48 emergent bilingual fourth graders since September, from her home.

But it’s safe, especially in Austin, where COVID-19 hospitalization and death rates remain very high and vaccinations very rare. And she’s working very, very hard—up to all hours of the night—to make it work for her students and their families.

“I will always be grateful for the way families have come together to support their kids through this difficult time,” she says. “And though I am exhausted every day by the demands of virtual education, I just feel an intense need to put forth all my efforts for the kids and families I serve. I know my colleagues feel the same.”

'I Feel Very, Very Privileged

In January, the district told about 970 high-risk educators to return to their buildings or take leave, which most didn’t have, or quit. While Sweet has received an extension of her accommodation through March, Valdez was among the return-to-work-or-else group.

“I certainly don’t want to die, and I don’t want my 79-year-old mother to die either!” says Valdez, who herself is a high-risk person. As the date for returning to school loomed, “I was trying to figure out what to do. I was thinking about our mortgage, and whether I could take unpaid leave. I actually looked into a living will. I was scared out of my mind.”

Her students and parents were supportive of her work from home. One held a sign at school district headquarters with Valdez’ photo on it, saying, “I don’t love virtual learning but I love my teacher. Keep her safe.”

And she wasn’t the only one. Many hundreds of high-risk, especially vulnerable teachers were terrified. With the union filing grievances and organizing “speak outs” for parents and students directed at school board members, tensions were running high. Suddenly, in the midst of this, the district announced it had secured vaccines at a local hospital for about 500 of its most vulnerable educators.

“I wanted to hug the lady who gave me the vaccine,” says Valdez. “I was so thankful. I feel very, very privileged.”

Only 18 percent of educators have received the vaccine so far, according to recent NEA research, even though NEA leaders have been asking state and local authorities to prioritize the vaccination of the nation’s 5 million educators since December. (Check out a recent map that shows where teachers are currently eligible.)

It's Not Over Yet

Since receiving the vaccine, Valdez has returned to her school building’s kindergarten classroom, where she has about a half-dozen 5- and 6-year-olds that she must constantly remind to stay 6 feet apart from each other. They want to be near her and each other, and she wishes they could—small, cooperative-learning groups are a hallmark of kindergarten-skills building. At the same time, Valdez also has another, larger group of students online, who she simultaneously teaches.

Valdez is so, so thankful to have received the vaccine, but it hasn’t eliminated her fears around the pandemic. Her students, their parents, their grandparents—they’re all still at risk. “It’s better, but I’m still scared out of my mind,” she says.

“I love my union! If we had not pushed, I am certain we would not have gotten what we got,” says Valdez. “Without a union, people can treat you however they want. Together, we are stronger. And I really feel like we were stronger together, in the face of this pandemic.”

The recent vaccinations are only part of the puzzle, notes Sweet. Most teachers and education support professionals (ESPs) aren’t vaccinated, and yet “cafeteria staff, bus drivers, paraprofessionals and so many more are providing essential services to our students with the highest needs,” she says. “There must be a deliberate, concerted efforts to protect all of our staff.”

Vaccinations also must be extended to more family and community members. The neighborhood where she works has been hard hit by COVID, and local data shows that it has a disproportionately low rate of vaccination. “The families I work with need immediate access to the vaccine. We are not safe yet. We won’t be for a while. We need district administration and state education officials to do more to protect kids, families, and adults working in schools.”

For her part, she doesn’t know what will happen when her current accommodation expires in March. Her doctors tell her that her immune system isn’t ready for a return, but Sweet used up all of her medical leave during her surgery and chemotherapy. “I love my job. I love my principal. I love my school. I love the kids and families I work with. But I am terrified.

“I’m just trying to survive, you know?”