“You have to be here to get there.” That’s what Brittany Jones tells her second graders, instilling in them that strong attendance at school is the path to achieving great things in school and life. It’s never too early to start talking about attendance, says Jones, who teaches in Charlotte, N.C.

When Jones asks her class who wants a bright future, hands shoot into the air.

“Okay,” she says. “That’s why we have to be in school daily.”

Chronic absenteeism—when a student misses 10 percent of school days or more in one academic year—is a persistent nationwide problem that peaked during the pandemic. And many schools are still working to get students back to the classroom.

Some 30 percent of U.S. public school students were chronically absent during the 2021 – 2022 school year, while the pandemic was still raging. That was up from 16 percent before the pandemic, according to a 50-state analysis by the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Fortunately, schools are making progress. Data from the Department of Education shows that the rate of chronic absenteeism fell to 20 percent during the 2023 – 2024 school year, the most recent year for which data is available. Though the number is going in the right direction, it’s still well above pre-pandemic levels.

Educators know that chronic absenteeism takes a toll on students’ achievement and social and emotional well-being, among other negative impacts. But what are the root causes? And what can we do about it?

“The vast majority of kids aren’t missing school because they don’t care,” says Robert Balfanz, director of the Everyone Graduates Center. They’re missing school for many reasons, he explains, which could include bullying, not getting the academic support they need, or a lack of health care or reliable transportation.

Attendance Works, a nonprofit focused on reducing chronic absenteeism, identifies four core reasons that kids miss school: Barriers to attendance, aversion to school, disengagement from school, and misconceptions about the impact of absences.

“Each student is different, and each has their own story,” says Vanessa Prorok, an attendance interventionist at Mundelein High School in Illinois. “Educators need to work together and get to know our students. Some have crippling anxiety, others have challenging home lives, or they don’t get the help they need and feel they’ll never catch up.”

Prorok recommends that educators spend the first month back at school getting to know each student.

“That way, if we see a pattern of low attendance, we can more quickly get to the why and intervene,” she says.

These are some of the ways educators across the country are working to understand the barriers students are facing and provide solutions that keep kids in school.

1. Make schedules flexible.

At the high school level, some students miss school because they have to work during the day.

“I had a student whose family was about to lose their home, and the student had to start working immediately,” Prorok says. “That’s where offering some flexibility is critical.”

For students who must work, Prorok partners with her team on flexible schedules where they can leave early or come late and take classes on a computer.

Schools with large populations of students who experience poverty have especially high rates of chronic absenteeism. During the 2022–2023 school year, more than half of schools in which at least 75 percent of students receive free or reduced-price meals had “extreme” levels of chronic absence, according to an analysis by Attendance Works. The report defines extreme chronic absence as when 20 percent of students in a school miss almost 4 weeks during the academic year.

2. Provide clothes and hygiene products.

Poverty can impact attendance in unexpected ways. Most students want to fit in and wear the latest fashions, but when they have dirty or ill-fitting clothes, they may feel ashamed and fear being teased. Staying home may feel like the better option.

That’s where educators like Jones and Prorok say paying close attention to students can help. If they wear a lot of the same things, or if a few students don’t have clothes that seem to fit, put a flyer up about local clothing donation sites or thrift stores where everyone in class can see it.

Some schools, especially community schools, offer clothing closets or rooms with everything from shoes and socks to winter coats and personal hygiene products. Jones’ district offers Classroom Central, a free store where teachers collect items students need.

“I go a couple of times a week and grab things like socks, toothbrushes, and toothpaste,” she says. “I can get kids a new backpack so they don’t feel embarrassed that they might be the only ones without a backpack.” (To start a program like this in your school, explore online resources, such as catiescloset.org or josiescloset.org.)

For kids who experience homelessness or who can’t afford a laundromat, some schools provide washers and dryers on-site, paid for by local businesses or grants from manufacturers like Whirlpool. (Learn more at whirlpool.com/care-counts.html.)

3. Help students get to school.

Transportation is another major barrier, especially for students living in homeless shelters or who frequently move residences.

California’s Coalinga-Huron Unified School District uses vans and provides gas cards to families to get some students to school. Last year, the district had enough students living at a local motel to include it as a school bus stop.

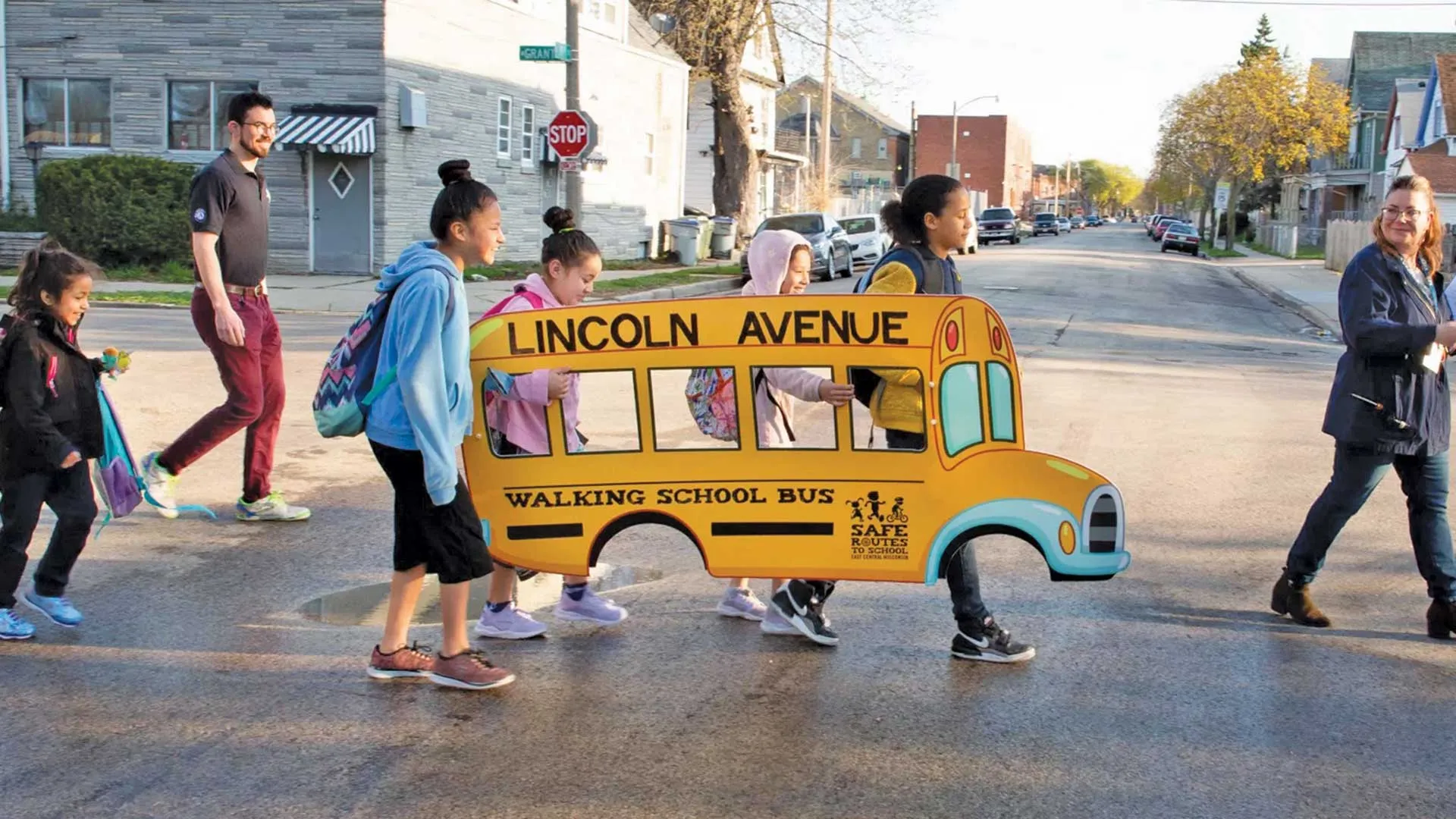

Other students miss school because of neighborhood violence or dangerous intersections along their route to the campus. Some schools and communities create “walking school buses,” among other approaches to keeping kids safe. (Learn more at saferoutesinfo.org.)

As bus driver shortages persist nationwide, safer walking routes are even more important, says Donna Christy, president of the Prince George’s County Educators’ Association, in Maryland, and a member of the county’s Truancy Study Workgroup.

“In our district, walking radiuses expanded because of the shortage, so we need to make sure those routes are safe and that we have enough crossing guards,” Christy explains.

Quote byLisa Dillingham, Teacher, Dover, N.H.

4. Ease anxiety.

Lisa Dillingham, a middle school teacher in Dover, N.H., says students have more anxiety than ever.

“Their anxiety can be physically debilitating,” she says. “Last year, a student had an anxiety attack, was flapping her hands wildly, and said she couldn’t breathe.”

When a student experiences that level of anxiety, their risk of skipping school skyrockets, Dillingham says.

“It’s critical to get the person access to mental health providers, but also to ease the student’s mind throughout the school year,” she says.

“Students … put a lot of pressure on themselves, so I remind them that it’s OK if they don’t get perfect scores or perform lower than expected on a test or project,” Dillinghan explains. “What’s important in the long run is that you’re here, your friends are here, and the fun parts of the school day are just as important as the rest.”

Dillingham’s aim is to let her kids be kids and to help take self-placed burdens off their shoulders.

“Students need to learn as early as possible how to cope with anxiety, …or their risk of chronic absenteeism and not graduating snowballs in high school,” Dillingham cautions.

5. Provide a school within a school.

Prorok had one student who was absent for 300 days because of anxiety about coming to school. When students miss that much school, she says, the anxiety builds up, making it feel impossible to return. Some figure there’s no point in even trying.

Prorok and her team of counselors, school support staff, and case managers are able to get students who miss dozens, even hundreds, of days to come back by agreeing to learn in a classroom designed for chronically absent students. This space allows them to work on their credits without the anxiety or distraction of a regular classroom.

“We have only 9 or 10 students at a given time, and it’s quiet with low lights,” she explains. “They catch up on their work and credit recovery, and we modify their schedules so that they can eventually return to some or all of their classes. Maybe they come for one class. … Others stay all day. The main goal is to get them to graduation.”

The girl who missed 300 days now comes to school every day. She uses a district computer program for her coursework and attends English class in person. She also took an elective in person with her sister, who made her feel more comfortable.

Creating this “school within a school” has been remarkably successful. Mundelein High now has a 95 percent graduation rate. (To find out if your district offers a similar program, ask your administrator or district office.)

6. Create a sense of belonging.

“Let’s face it, middle school is a very challenging time in a student’s life,” Dillingham says. “But without a sense of belonging or someone to talk to, [school] can be unbearable at any grade level.”

Getting kids into clubs and activities, she says, is a proven way to lessen chronic absenteeism. A variety of studies, including one by the National Center for Education Statistics, show that participation in clubs and extracurricular activities reduces absenteeism and builds a stronger sense of connection to school.

“They offer an opportunity for students to be with people with similar interests who care for them, which is especially true for kids in the LGBTQ+ community,” Dillingham shares. “They build relationships with a trusted adult, or small group of kids, and that’s huge for making school a supportive place.”

7. Make classes meaningful.

“How can we keep students engaged if all we teach them can be found on Google?” asks Christy. “A lot of students decide they’re wasting their time in a classroom that’s not teaching them what they need.”

She notes that schools must adapt curriculum and standards to make them more relevant to students today.

In history class, for example, rather than teaching and testing on facts and figures and who was on what side of a war—all information that can be found online—Christy recommends getting to the causes with questions that spur critical thinking and discussion.

“Let’s dig deep on logic and reasoning and make lessons relevant to the times we’re in by exploring the rise of AI, different technologies, and disinformation,” she says. “Make it relevant, relatable, and collaborative. Let students get up from their desks so they can walk around and work together.”

Jones agrees. She knows she must meet certain standards, but she infuses lessons with her own materials to make them culturally relevant to her students. She avoids endless worksheets and embraces technology and the online learning games her students love.

Her bottom line: “Make school more fun and create a place where they want to come and learn.”

Share This

If chronic absenteeism is a problem in your school, share this article with your colleagues and administrators, and try some of the programs on these pages.