Key Takeaways

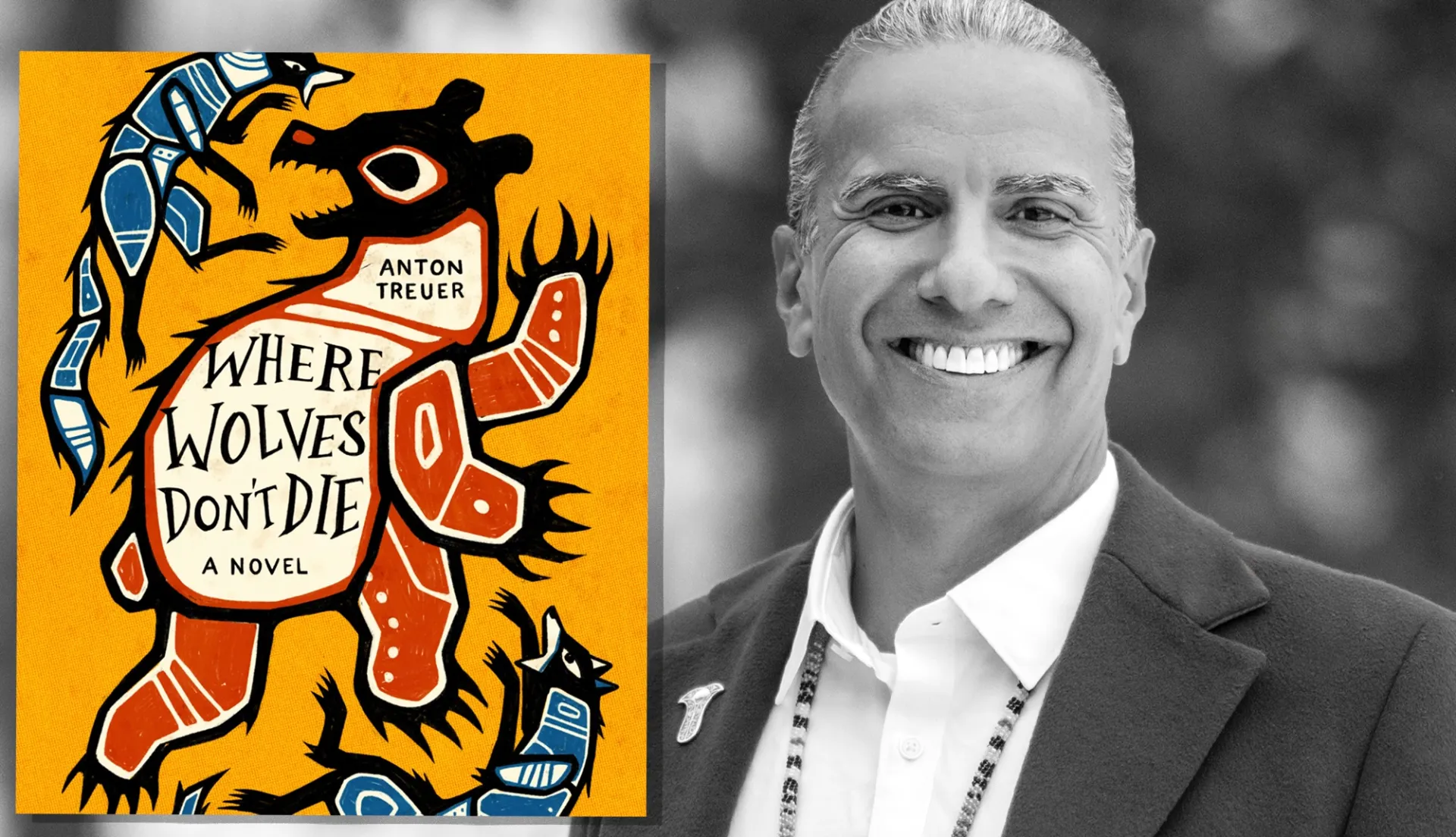

- "Where Wolves Don't Die" is an Indigenous YA mystery thriller with lessons for all students about growing up.

- About 87 percent of America’s education standards mentioning Indigenous people and cultures are from events prior to 1900, teaching students that Native culture is something that happened in the past.

- The internet abounds with toxic masculinity messages. This novel is an antidote, showing how family, community, and Native American traditions, like all cultural traditions, help young people develop a healthy maturity.

Ezra Cloud hates living in Northeast Minneapolis and all the dirty snow that piles up on street corners. And he really hates Matt Schroeder, the neighborhood bully who ridicules him and his friend Nora about their Native heritage. But does he hate him enough to burn his house down after they have a fight? The police seem to think so. Matt’s father and uncle both die in the fire, and Ezra becomes the prime suspect of arson and murder.

Knowing his innocence, Ezra’s father sends him to his grandparents’ house on the Nigigoonsiminikaaning First Nation reservation in the Canadian wilderness to protect him from retaliation during the criminal investigation.

Sizzling with suspense, Where Wolves Don’t Die, a YA novel by Anton Treuer, also offers lessons on coming of age amid fear and loss.

As Ezra, the main character, navigates the challenges of adolescence and the mysteries of the wilderness and his Native culture, he stumbles upon a life-altering journey while looking for the clues to solve the crime he’s accused of.

A Healthy Alternative to Toxic Messages on Masculinity

Ezra is grieving the death of his mother and doesn’t know how to talk about it. He has a tense relationship with his father, who moved them to the city for his job as professor of their Ojibwe language at a local university. And he misses his grandparents and their life on the reservation as he tries to fit in with his mostly white classmates.

Unhappy teens often turn inward or to the internet where unhealthy messages about masculinity abound.

According to an October 2025 Common Sense Media report, 94% of boys are online daily through social media or gaming, and 73% are regularly being exposed to content with stereotypes about what it means to "be a man."

Where Wolves Don’t Die shows students another way – how connecting with family, nature, and tradition can offer a sense of belonging.

As the father of nine children, almost all now grown, Anton Treuer knows a little about adolescent development.

“Every other year we have had a kid heading out the door, and I know the struggle of transitioning from a young person to an adult,” he says. “Kids need to break from their parents in a healthy way, and they crave independence on one hand and belonging on the other. The story shows how a 15-year-old Native kid grapples with this stuff, but with tension and energy and excitement that keeps you moving along.”

You don’t have to be a parent to see how many toxic messages are out there, and Treuer wanted to present an alternative. Boys are bombarded with messages about rugged individualism, consumerism, and competition.

“But we survived cave bears and saber tooth tigers not because we competed, but because the person in the next cave loved us,” says Treuer, an author and professor of the Ojibwe language at Bemidji State University in Minnesota.

What the reader finds with Ezra is that he doesn’t go it alone, redefining what adulthood and manhood should look like.

A lot of YA fiction, Treuer says, focuses on peer-to-peer relationships, like the cafeteria style “mean girl” stories.

“But teens’ lives are filled with other characters of different ages as well as family members,” he says. “In Ezra’s world, there’s friendship and new love, but he also creates healthy connections with his grandparents and his father and with the natural world.”

Hunting and trapping are a way of life in communities across America, but in Where Wolves Don’t Die, Treuer’s first work of fiction, readers learn about hunting and running traplines in an Indigenous context.

Family and Community Traditions Celebrate Coming of Age

“In Native culture, we have a reciprocal relationship with the natural world,” he says. “We aren’t given dominion over nature. We are part of the web of life, not its masters.”

It’s in this context that Ezra learns about his place in a community and gains a sense of belonging.

After he successfully traps a moose with his grandfather, they hold a big feast. Following Ojibwe tradition, Ezra’s grandfather offers him a spoonful of the cooked moose meat, which he must refuse three times before eating it. He refuses the first bite because he must think about all the kids who don’t have enough to eat. He refuses a second time to acknowledge the elders who can’t go out to hunt for themselves. And he refuses a third time to show respect for the family and community members who came to the feast to support him.

When his grandfather offers him a bite for the fourth time, he can eat. That’s when he is told that until that day, he was a dependent, but now he is providing for all of them, and that is what it means to be an adult. The message is that when you become old enough to gather resources, you must also think about those who don’t have enough, and about your elders, family, and community.

At the end of the feast, Ezra helps package the moose meat and distribute it to the community. “If I had anything else to give, I would,” he says.

The first kill feast is a ceremony Treuer, and all his children have gone through. He says it’s a life altering ceremony, and he hopes readers will think about their own culture's coming of age traditions.

It's Not a Native Story, It’s a Human Story

“Sometimes the literary world has this idea that if you want to understand the Native, Black, or female experience, you should read those authors,” Treuer says. “But if you want a book about the human experience read a white author’s novel.”

Where Wolves Don’t Die is a story about a Native experience that is also universally human, he explains. Who hasn’t dealt with a bully? Who hasn’t yearned for connection and belonging? It’s a reflection on the universal experience of growing up and how we can do that in a community- and family-based way.

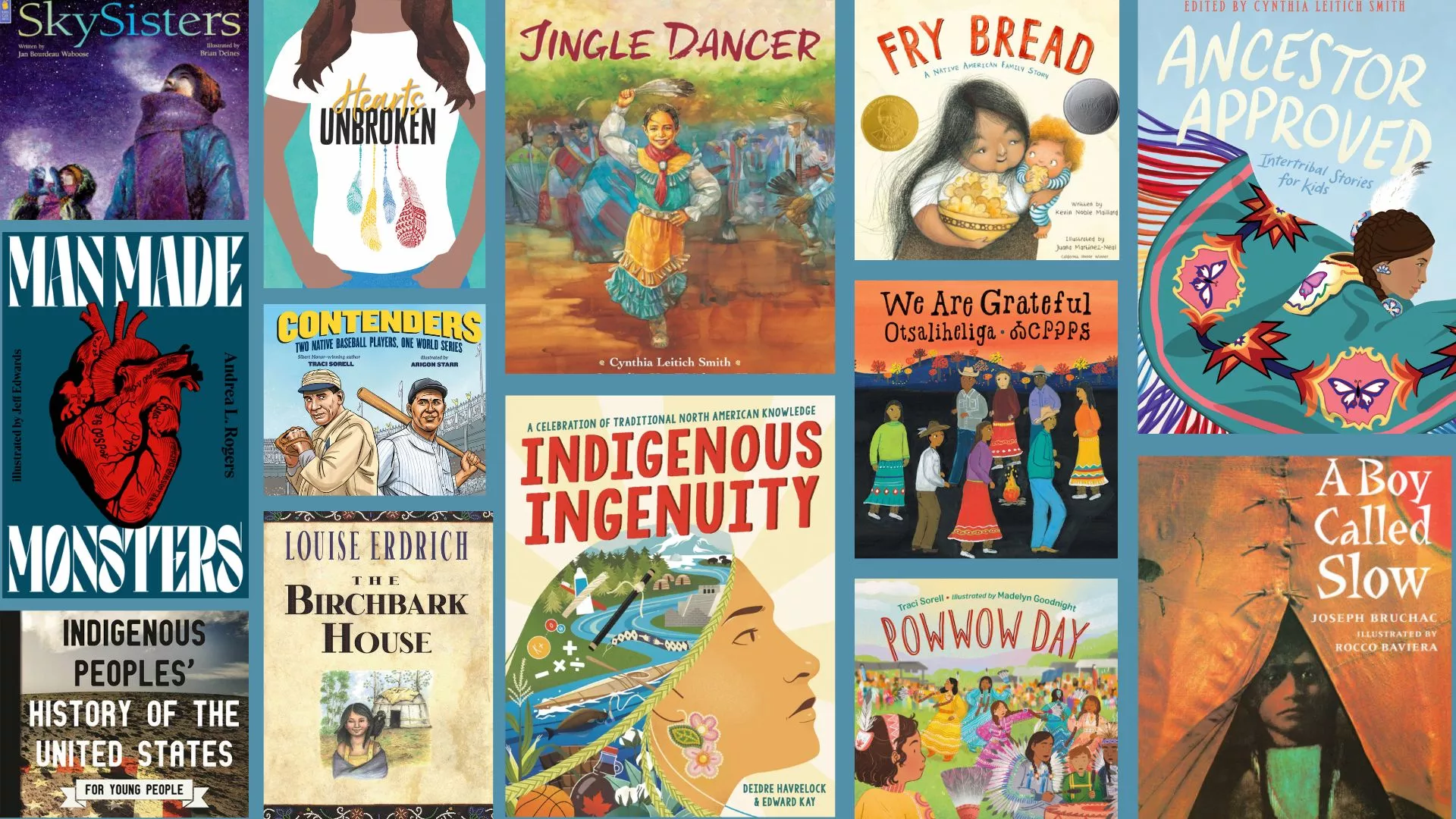

At the same time, the book takes the reader into the Canadian wilderness and an authentic Native culture, one that is happening right now.

According to research, 87 percent of America’s education standards mentioning Indigenous people and cultures were limited to pre-1900 contexts, effectively erasing their modern history and existence for many students.

“Kids learn to think about Native Americans as something that happened in the past,” Treuer says. “To be sure, Natives have a long history. The Native population has been living here in Minnesota longer than humans have been living in England! But our education systems have been part of the erasure of a continued vibrant population that is very much alive and all we can learn from it.”

The legend of how the crow got its name is important, he says, but an eighth-grade student doesn’t relate to that story nearly as much as one about a boy riding a snowmobile across the wilderness trying to find his grandfather and running into a pack of wolves.

“A contemporary story about a Native boy helps battle stereotyping while also offering lessons that anyone can learn about growing up and honoring your community and your place in it,” says Treuer. “It doesn’t swim through the tragedy and trauma of what Native culture lost but speaks about the living culture that is here and how kids can get to healing.”