Many young Americans have lost faith in democracy. That’s the troubling finding of several surveys conducted over the past five years.

About half of the Gen Z participants (ages 18–25) said democracy “makes no

difference,” according to a 2022 Penn State University survey, and nearly 30

percent said living under a dictatorship “could be good.”

Let that sink in.

A 2025 survey by the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), at Tufts University, similarly found that a third of Americans ages 18–29 “do not buy into the value of democracy and show higher support for authoritarian governments.”

Although the remaining two-thirds said they generally support democracy, they do little to engage in it.

The study found no major differences between the group that still values democracy and the group that does not in terms of age, gender, city-rural division, or even party affiliation.

So what does influence whether or not young people value our system of government?

“At the top of that list is education, access, and community support,” says Alberto Medina, a co-author of the CIRCLE report. “Of course, teachers are critically important to helping students understand and value democracy, but so are their peers,” he says.

When groups of students work together to understand how our government functions and even take on problems they care about, he says, it “can help show the deeply skeptical that there is something here worth saving.”

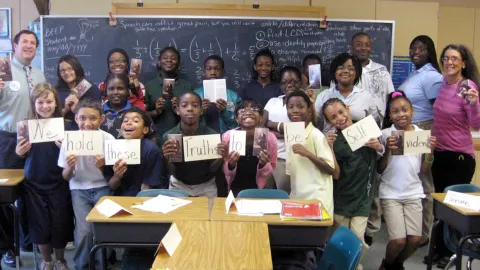

While great social studies courses are critical for students of all ages, a student’s civic education is not limited to those classrooms. In fact, public schools—as institutions that welcome all students regardless of race, first language, family income, or abilities—can serve as living laboratories of democracy.

It’s never too early to teach civic engagement

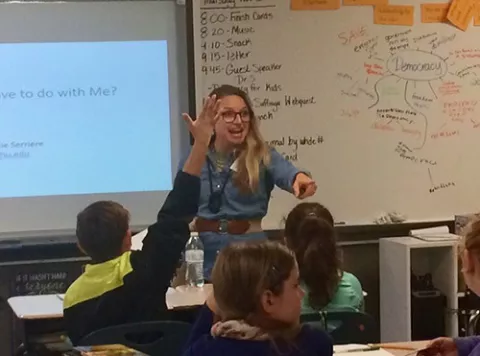

Here’s one way to think about it, says Stephanie Serriere, a professor of social studies education at Indiana University Columbus: “Public schools are one of the first civic spaces our children enter, and it is up to you to purposefully teach the principles of democracy,” Serriere tells her classes of future educators.

That teaching, she says, should begin in kindergarten.

Serriere developed her theory of “carpet-time democracy” in her years as an elementary school teacher, when she observed her young students’ natural interest in fairness and equity. There are many creative ways to harness those instincts, she says.

For example, when elementary age students get to discuss and decide classroom rules, they become tiny framers of a founding document that applies equally to all and guides their experience in the classroom.

When older students identify things they wish they could change—as tweens and teens tend to do—educators can walk them through the process of inquiry. This may include polling their peers, gathering research, and using their findings to advocate for change.

Research shows that asking students to gather the perspectives of their peers—which is at the heart of many of these projects—can be the springboard to a lifetime of empathy, according to Serriere. That’s a necessary component in a democracy, she adds.

What can you do to foster civic learning in the classroom and beyond?

NEA Today asked several educators around the country for their advice.

Teach students how to build their case

Laura Ellis, library media specialist, Wheaton High School, Silver Spring, Maryland

Many students want to speak out. We can teach them how to make their voices heard by the right people.

Last year, when I heard the Trump administration was cutting funding for libraries and museums, I started writing to my elected leaders, asking them to fight those cuts. I quickly realized that this could be a service-learning opportunity for students.

As a lunchtime activity, I teach interested students how to write a strong, fact-based letter, based on a visit to a local library, where they ask an employee questions about the resources and programming they offer to the community. The students learn not only what kinds of questions to ask, but also the etiquette of conducting an informational interview. We practice at school before the real interview so they feel confident.

After they gather information about the amazing programs the library has for kids, teens, adults, and seniors alike, the students write to our state’s U.S. senators. I have a template for guidance, but encourage them to include a personal story that will make their letters unique.

This project teaches students to value community resources and learn how to advocate for them.

Emphasize respectful dialogue

Lauren Hallgring, eighth-grade civics teacher, Neptune Middle School, Neptune, New Jersey

Our state passed a law a few years ago mandating at least one semester of civics instruction before students leave eighth grade. It’s an incredible opportunity to introduce some finer points of the U.S. Constitution and

to teach students to engage in productive dialogue.

Things can heat up in a middle school classroom very quickly, so I am very intentional at the beginning of the course in talking to students about respectful discourse. Yes, they need to learn to form an argument, but it’s just as essential for them to actively listen.

Allowing students to bring up issues and talk about what they are seeing and hearing in their world is critical. They will begin to respond to each other—it’s a beautiful thing to see—and the teacher’s role is largely to monitor and moderate.

I never get on a soapbox or make my own political views known. Instead, I ask a lot of guiding questions and give students practice in finding evidence from primary sources.

Last year, for example, my students had a lot of concerns about immigration. So we went back and read the 14th Amendment to the Constitution before we started the conversation. This strategy helps students learn to support their arguments with evidence rather

than emotion.

Channel students’ passions into community building

Preya Krishna-Kennedy, history and geography teacher, Bethlehem High School, Delmar, New York

In my classes and in the after-school groups I co-advise, I always emphasize that in our democracy, we have the power to make change, even beyond the essential acts of voting and holding elected leaders accountable.

Students for Peace and Survival is a social justice group initially formed by students during the Vietnam War. I took on the role of co-advisor in my first year of teaching, and honestly, I credit this group with keeping me in the profession. This club attracts students who are so motivated to solve problems and help their community, it gave me a boost when I was an overwhelmed new teacher. Now I’m in my 29th year.

This group organizes events like a Pronouns Day celebration to start conversations and support students who have changed their pronouns. They do a coat drive for a refugee group in Albany, N.Y. They hold fundraisers to address food insecurity in the area, and they’ve organized protests to ask the district to divest from fossil fuels.

Another group I advise, ALANA (African, Latino, Asian, and Native American), spearheads celebrations for Black History and Hispanic Heritage Months that include activities like reading books on those topics to elementary students.

When kids are this engaged in giving back to their community, they are exercising empathy and problem-solving—essential skills in a healthy democracy.

Connect historical lessons with the real world

Lem Wheeles, government teacher, Dimond High School, Anchorage, Alaska

In both my government and U.S. history classes, I host a debate set in the time period that the Constitution was being drafted. I assign roles—Federalist or Anti-Federalist—and give students some readings authored in 1788. Then, they debate whether or not to ratify the Constitution from the point of view they were assigned.

Sometimes when we’re discussing contemporary issues or elections, students become hesitant or express disdain for how lawmakers are handling things. I keep asking questions like, “What can we do about it?” or “What needs to change?”

If there’s one thing I hope everyone leaves my class knowing, it’s that we have a participatory form of government, and if we don’t engage, we’re letting other people frame the debate and make the decisions.

Last year, I saw just how well that message got through. I was at a school board budget meeting, and I was surprised to see several of my students walk in to speak out against cuts that would have increased class sizes and reduced electives and activities.

They were fired up about proposed cuts to middle school sports, which wouldn’t affect them since they were already in high school. The whole thing made me incredibly proud—they were well prepared and speaking up not only for themselves, but for others. That is how democracy thrives.

Quote byLem Wheeles, government teacher, in Alaska

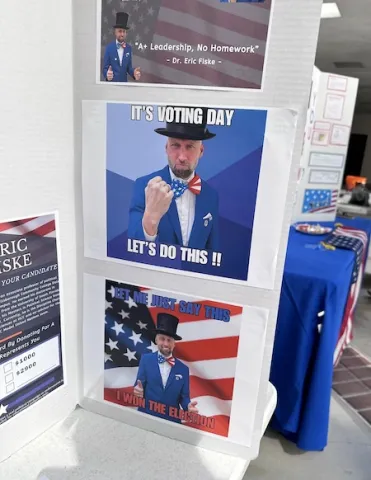

Don’t be scared to cover elections—have fun with it instead!

Eric Fiske, political science professor, Hillsborough College, Tampa, Florida

The energy really builds in my classes when we talk about campaigns, elections, and voting.

We’re living in politically charged times, and certainly in Florida there are vague and threatening policies that make educators think twice.

But as a political science professor, teaching these topics is essential to my students’ education.

In my honors American government class last year, I “ran for office” as a candidate from a fictional party and asked my students to be my campaign team.

They ran with it. The next thing you know, they are running social media platforms, having me sit for photo shoots, and polling their peers to determine my campaign priorities and slogans.

Once they were on a roll, I threw them some curveballs. When big things happened in the real world, I asked them how I, in my role as the candidate, should respond. I tell my students, ”You can know everything there is to know about American government, but if you don’t do anything with that knowledge, you’re giving up your role in shaping the society you live in.”

Civics Education: Teaching About Elections and Citizenship

Knowing the history, principles, and foundations of American democracy, and the ability to participate in civic and democratic processes, are vital to our citizenry, but civics engagement goes beyond memorizing historical documents or casting a ballot. It requires developing students’ critical thinking and debate skills, along with strong civic virtues.

We've compiled resources and advice from NEA members and other experts to help you bring civics education into your classroom.

Go to nea.org/Civics for more ideas on promoting democracy throughout your school.

We Want to Hear from You

Get more from