Key Takeaways

- Two years ago, Evergreen administrators were looking to cut faculty to balance its budget. Faculty had a different idea: instead of shrinking, they would focus on growing.

- The United Faculty of Evergreen's student-recruitment work—which focuses on informative conversations between faculty and potential students—is now embedded in its collectively bargained contract.

- Today, student enrollment is reaching historic levels. Campus morale is high and faculty-staff relationships are better than ever. Evergreen's success may be inspiration for other colleges struggling with national issues around enrollment.

Student enrollment began sliding at Evergreen State College more than a decade ago, as it did at colleges across the country. It was an issue, but it wasn’t dire—until the pandemic hit in 2020. And then it became a full-blown budget crisis.

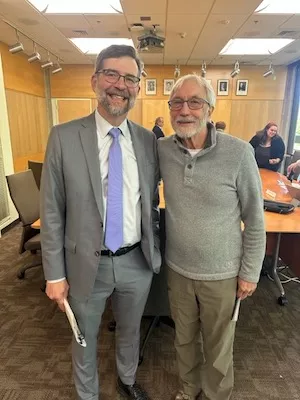

That year, Evergreen faculty salaries were cut by 10 percent. Furloughs also were agreed to. These measures helped, but not enough. By 2021, Evergreen State administrators were saying the institution had too many faculty members. Layoffs would be necessary to balance the books—and up to one in five tenured and tenure-track faculty members could lose their jobs. “I’d been there for six years and had tenure, and I could have been laid off,” recalls Evergreen faculty member Brad Proctor.

But the United Faculty of Evergreen (UFE), which represents about 190 full-time faculty and adjuncts at Evergreen, saw the problem from a different angle. They turned it over and landed it upside-right. It wasn’t that there were too many educators, faculty concluded. The problem was too few students—and the union wanted to do something about it.

"What happened here is the result of the faculty union,” says Proctor. “It came out of us saying, ‘Why can’t we recruit students?”

Growing Evergreen

This past fall, Evergreen, a non-traditional liberal arts college in Olympia, Washington State’s capital city, experienced its largest increase in student enrollment in 40 years. The student body of 2023 – 2024 is 10 percent bigger than the student body of 2022 - 2023. In January, the college and union jointly announced that layoffs were off the table.

23%

1980

While Evergreen isn’t totally out of the woods, it is strongly moving forward. “Rather than working on shrinking, we’ve been working on growing,” says Jon Davies, the chair of UFE’s bargaining committee.

This work of growing began formally in late 2021, after months of dogged conversations between faculty, staff, and administrators, when the college and union negotiated a temporary agreement. Setting aside talk of layoffs, the agreement instead established “a plan to use the faculty as a resource, in combination with the College’s other recruitment resources, to assist in increasing student enrollments during the term of the Agreement.”

As bargaining chair, Davies had found an interested partner in Evergreen’s president, John Carmichael, who recalled when he was a high school senior, decades earlier, and a college faculty member reached out to him. Like about a third of Evergreen’s students today, Carmichael was a first-generation college student—his parents didn’t have college degrees. “First-generation students aren’t always confident that they belong in college,” he says. “To have contact from a faculty member like that is very reassuring.”

The signed agreement provided for two “faculty organizers for student recruitment” to develop and lead the work. They were Proctor and Nancy Koppelman, an Evergreen graduate who has taught at the college for nearly 30 years. Across 2022, the duo worked with admissions staff and coordinated more than 40 UFE members, plus other employees, to engage in many hundreds of video conversations with potential Geoducks. (Evergreen’s mascot? Speedy the Geoduck, a large burrowing clam.)

The team prioritized students who had gotten into Evergreen but hadn’t decided if the unique campus was the right place for them. Their goal? To increase “yield,” the percentage of admitted applicants who say yes.

The Disappearing Student

What does it take to get a student to say yes to college these days? Between 2019 and 2022, undergraduate college enrollment dropped 8 percent across the U.S., the steepest decline on record, according to federal statistics.

Unnerved by the increasing cost of college and the prospect of student debt, or maybe just thinking “why bother,” nearly four out of 10 graduating high school students are opting for jobs instead. In Washington State, about 50 percent of the high school class of 2021 enrolled in college—down 9 percentage points from 2019, according to a Seattle Times analysis. And it’s not just Washington. In Indiana, in 2015, about two-thirds of high school students went on to college. By 2021, a little more than half did.

The COVID-19 pandemic can be blamed, in part—but students were already opting out of college before the pandemic started. College enrollment peaked in the U.S. in 2009, and it’s been on a decline with fits and starts since then. The steepest decline is observed among men—and also among Black, Hispanic, and low-income people. In Tennessee, for example, while the overall college-bound rate has fallen to 53 percent among all high school graduates, Fortune points out, it’s just 35 percent among the state’s Hispanic graduates and 44 percent of Black graduates.

These trends are troubling. Where are the future teachers, nurses, pharmacy techs, and others?

Concerned faculty and administrators may want to look toward Evergreen for the answers, suggests UFE President Julie Russo. What’s happening in Olympia with UFE’s student-recruitment project “feels like something other institutions may want to pay attention and learn from,” she says. “It’s a really different approach to these issues.”

“I want to know what they want.”

At Evergreen, and on campuses across the country, faculty believe in what they’re doing. They know a college education can be transformative. Certainly, it leads to more money—about $22,000 a year among 20-somethings— but it also helps students to pursue their passions and achieve their dreams.

Evergreen faculty especially believe that what they offer is special—because it is. It’s not just the quirky mascot. At Evergreen, instead of declaring a traditional major, students create their own pathways to degree or follow an interdisciplinary program of study. Most classes are team-taught by two or more faculty members. Instead of grades, students get narrative evaluations. The author of the popular “Colleges That Change Lives” says “it makes education more of a discussion and a journey than a competition.”

This often needs to be explained to potential students, notes Proctor. As a result, the recruitment conversations between Evergreen faculty and potential students aren’t so much “a persuasive conversation,” he notes, as “an education opportunity.”

Quote byNancy Koppelman, Evergreen State faculty organizer

When Koppelman has a video conversation with a potential student, she first wants to find out who they are. “I want to hear their voice. I want to hear their laugh. I want them to feel comfortable telling me what’s real, what’s true. I’ve learned that a lot of students get by in the educational system by giving teachers what they want—but I want to know what they want,” she says.

Then she explains how Evergreen works. They look through the college catalog together, finding programs in the student’s area of interests. “I tell them that the descriptions of programs are like invitations to an adventure. And that’s really true!” says Koppelman. “It’s not just ‘here’s what is covered,’ it’s an invitation…to dig in.”

These conversations have become how Evergreen students first encounter Evergreen faculty—and they accurately foretell the faculty-student relationships to come. “Students here have extraordinarily close relationships with faculty members,” says Carmichael. “Something I like about [this recruitment work] is that it’s an authentic representation of what it’s like to be here.”

This year, Evergreen’s yield—that is the percentage of admitted students who decided to enroll—increased by 4 percent. “That’s a hard number to move and 4 percent is big move,” says Carmichael. At the same time, student retention also is increasing, as the students who choose to attend are more informed.

Article 30: Growing Evergreen

In 2023, UFE’s three-year contract was expiring, as was the temporary agreement that created the faculty recruitment project. With this in mind, the union—which is part of a faculty union network, the United Faculty of Washington State, dually affiliated with WEA/NEA and AFTWA/AFT—made getting this work into the faculty contract its number-one priority at the bargaining table.

“It was our big ask… and we’re very proud of what we’ve done,” says Davies. The new contract, ratified this fall, provides for up to full-time release for two organizers during the school year and for part-time pay during summer months. It also requires the organizers to work with staff and administrators, such as admissions and employees. Other faculty who have been trained to have conversations can fulfill their service requirements by doing them. “Both sides recognized that it’s important work and needs to be compensated,” says Davies.

Beyond the rising enrollment numbers, faculty have noticed additional benefits. For one, the mood on campus is sunnier. “It’s really lifted all of us,” says Davies. Talking with students about the strengths of the college has reminded faculty how much they believe in their work. It’s exciting and affirming.

The required faculty-staff collaboration also has led to stronger relationships among faculty and staff members, rooted in shared respect for each other’s expertise, Russo notes. This is often atypical on college campuses and “its really kind of magical,” she says.

The project—driven by the union but supported by administrators—also has demonstrated how much the union and administration can achieve together. “At a moment when the union and administration could have turned on each other, I feel like we came together in a really constructive partnership,” says Carmichael.