Key Takeaways

- The behaviors of ADHD can be different from student to student, but there are strategies that help not only them, but the class as a whole.

- A common misconception about kids with ADHD is that they can control it, but it's a brain-based condition that affects executive functioning and is not something they can control without interventions.

- It is important to recognize that ADHD is not a deficit and that there are many highly successful adults who also have ADHD.

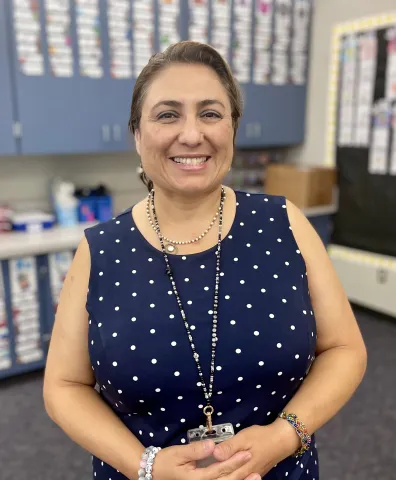

Every year Yesenia Guerrero, a special education teacher in California’s Lennox School District, buys with her own money a new wiggle stool for her students with ADHD, or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

“I’m trying to build up my supply,” she says. “They’re very expensive, but they work!”

Guerrero has experience with students who have ADHD in elementary through high school, some who have IEPs or 504s, and some that don’t. The most common trait she sees is their need to move.

That’s where the wiggle stools come in.

There are other kinds of seats that offer movement, but the main idea is to offer movement as a sensory break.

“Don’t get stuck on having everything always quiet, with everyone sitting still. A little noise, and a little movement is OK,” Guerrero says. “Offer different kinds of seats. Let them work standing up. IIf they want to sit lotus style or on their knees, let them. They need the release.”

ADHD Looks Different from Student to Student

While many students who have ADHD have traits that are easy to recognize – like attention seeking, blurting out, fidgeting, talking to classmates – others are quiet and may seem engaged, but their minds are elsewhere.

“They may have their eyes on you, or even stare at you, but their brain is wandering,” Guerrero explains. “They aren’t as impulsive in body movements, but they’re not paying attention even if they’re looking at you. When you call on them, they’ll snap out of a daydream.”

Just as there are some common traits exhibited by students who have ADHD, there are also a lot of common misconceptions. One of the biggest that Guerrero and other special educators find is that people assume the kids can control their ADHD, that they are somehow being willfully disobedient or inattentive.

‘These are very, very bright kids -- they just have a difficult time containing themselves and calming themselves down,” Guerrero explains. “They may appear to be lazy or unmotivated, but that is a total misconception. Their brains just work differently.”

Martha Patterson, who currently teaches middle school social studies but spent many years as a special education teacher for Central Kitsap Schools, in Washington state, agrees.

“There are a lot of people, including those in education, who think that kids who have ADHD can control it, or that they are acting out on purpose,” she says. “Even if a student has a 504 or an IEP, some still think they can control it. They can certainly manage their ADHD with therapies, accommodations and medications, but their behaviors are symptoms, not choices.”

Read More: What is it like to have ADHD?

Patterson has several students with ADHD, and her largest class is 31 students.

“I’m a veteran in my 40th year and there are days that are very frustrating, when a student is asking the same question for tenth time, or I have to repeatedly ask another to turn around and stop talking,” she admits. “In the early part of my career, when this kind of thing happened, I thought those students were just being naughty. Looking back, I realize, that kid probably had ADHD! Now I understand their brains are wired differently.”

What is ADHD?

ADHD is a brain-based, neurodevelopmental disorder and a life-long condition affecting the brain and its executive functioning. It affects about 11 percent of school-age children, according to Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD), and is characterized by developmentally inappropriate levels of inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity.

Medical research first documented children exhibiting inattentiveness, impulsivity and hyperactivity in 1902. Since that time, the disorder has been given many names, including minimal brain dysfunction, hyperkinetic reaction of childhood, and attention-deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity. In 1987, the medical community changed the name to ADHD to reflect the importance of the inattention aspect of the disorder as well as hyperactivity and impulsivity aspects.

There are three ways ADHD can present in a student: Predominantly Inattentive, Hyperactive Impulsive, and Combined.

On its website CHADD lists the symptoms for each:

ADHD predominantly inattentive presentation

- Fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes

- Has difficulty sustaining attention

- Does not appear to listen

- Struggles to follow through with instructions

- Has difficulty with organization

- Avoids or dislikes tasks requiring sustained mental effort

- Loses things

- Is easily distracted

- Is forgetful in daily activities

ADHD predominantly hyperactive-impulsive presentation

- Fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in chair

- Has difficulty remaining seated

- Runs about or climbs excessively in children; extreme restlessness in adults

- Difficulty engaging in activities quietly

- Acts as if driven by a motor; adults will often feel inside as if they are driven by a motor

- Talks excessively

- Blurts out answers before questions have been completed

- Difficulty waiting or taking turns

- Interrupts or intrudes upon others

ADHD combined presentation

- The individual meets the criteria for both inattention and hyperactive-impulsive ADHD presentations.

Supporting Students with ADHD

It’s likely educators will have at least one student who has ADHD in their classroom, but there are strategies that will work not only for them but for everyone in the room.

Patterson recommends strategic seating.

“I would give students who have ADHD seating near the teacher and away from distractions like windows or hallways, but it’s important to look at the class as a whole,” she says. “Don’t seat them next to a student who also has distractibility but do try to find a place next to a good role model who can model appropriate actions and focus and who they can ask for help.”

Maintain Routines and Repeat Reminders

Patterson also recommends setting and maintaining consistent routines so everyone knows what to expect each day or each class period and can focus their attention and memory on curriculum, not figuring out what to take out of their desk or backpack or when to pack up.

“When students come into my class, they always see on the screen the plan of the day, the materials they need, and what they will be working on. If a student needs a reminder, I’m happy to provide it,” she says.

Sometimes a student will ask to take out their Chromebook before it’s time, and when she says no there might be an outburst, an inappropriate word, or total shutdown and withdrawal.

“When that happens, I stay calm, speak to them in a calm voice, and not escalate,” Patterson says. “Then I remind the class what we’re working on and when Chromebooks come out.”

Other times, a student is just sitting and staring into space, Patterson says.

“They don’t know where to start and seem lost from the beginning,” she says. “These students need multiple reminders, even with a set routine.”

Guerrero says repeated instructions help when a student can’t focus on one thing, which is common with ADHD.

“I’ll have a student who can tell me what color my outfit is, what the neighbor said, and everything going on around the room,” she says. “But they can’t focus on the task at hand because their brain is so busy taking everything else in. They can get sensory and stimulation overload.”

Guerrero takes time to notice all the behaviors of her students.

“Are they completing assignments? Can they answer a question based on the classroom discussion? Sometimes their work is half done, and it’s all correct, but incomplete. They have great plans but then don’t follow through to the end. Their ability to attend to it, plan it out, isn’t there without guidance and support.”

Once they have that support, and have accommodations to remove distractions students with ADHD can become hyper focused, one task at a time.

The Power of Paraeducators

The best way to provide guidance and support, Patterson says, is to have a paraeducator in the classroom to work with students.

“Over the years I’ve seen that they most effective strategy is having that presence next to them, whether it’s a paraeducator or a teacher,” she says. “Last year, I was a resource support teacher supporting kids with math IEPs. I’d sit next to them and guide them through the problem step by step. That’s incredibly powerful. Staff power works.”

On October 11, the Trump administration laid off nearly all staff in the U.S. Department of Education's Offices of Special Education Programs (OSEP) and Rehabilitative Services (RSA).

The reduction-in-force affects the staff members responsible for roughly $15 billion in special education funding and for making sure states provide special education services to the nation's 7.5 million children with disabilities.

This, on top of persistent educator shortages and continued budget cuts, make it unlikely that general education teachers will have the assistance they need.

But there are some tools that can help, Guerrero says.

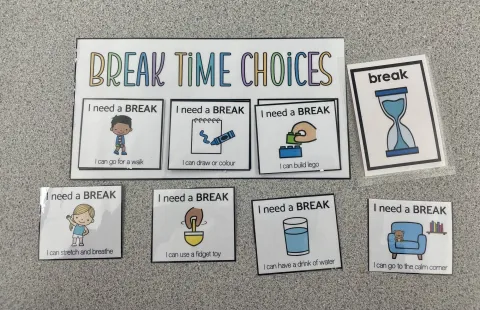

She recommends giving kids breaks. At her school, kids get a variety of break cards they can use throughout the day.

“A student will say, hey I need to play a break card, and they have cards for coloring breaks, quiet corner breaks, water breaks, and bathroom breaks,” Guerrero explains. “They get to choose the break category, and it helps prevent meltdowns and allows them to better focus after the break.”

Auditory signals also work – shake maracas when it’s time to take out new material, ring a small bell to indicate a new lesson is starting, she advises.

ADHD is a Difference, not a Deficit

Above all, Guerrero and Patterson recommend that educators and parents – and the students themselves – are aware that ADHD is not a deficit, just a difference.

“Let them know that there are lots of brilliant and successful people who have ADHD,” Patterson says. “I do a unit about famous people who were diagnosed with ADHD and made it work for them in their careers.”

Years ago, she had a student, who she recalls was a sweet, active and energetic eighth grader. He knew he had ADHD but didn’t want medication because he thought that being on ADHD medication would bar him from joining the military, which was his dream.

“My husband was active-duty Navy and we went to a military hospital for health care,” she says. “I told my doctor what the student thought about ADHD medication and joining the military. He said if ADHD medications were an issue with the military, half the doctors at the facility would be out of a job!”