Last fall, educator Lucy Real Bird found herself traveling across Montana, meeting with distinct Indigenous groups. At each visit, tribal members opened the proceedings with Indigenous prayer. Local drum groups performed a flag song (an Indigenous equivalent to the U.S. national anthem), and participants enjoyed traditional music, dancing, and foods.

Organized by Real Bird, with help from the Montana Federation of Public Employees (MFPE), these visits were part a groundbreaking initiative called Unsettling Montana. This effort brought together educators, community leaders, and activists in a four-day, six-city tour to ensure that Indigenous educators see themselves reflected in their schools and union leadership. The participants developed strategies to integrate Indigenous histories, languages, and worldviews into classrooms.

The tour stopped in Billings, Great Falls, Browning, Pablo, Missoula, and Bozeman, with each event tailored to the needs of local Indigenous communities.

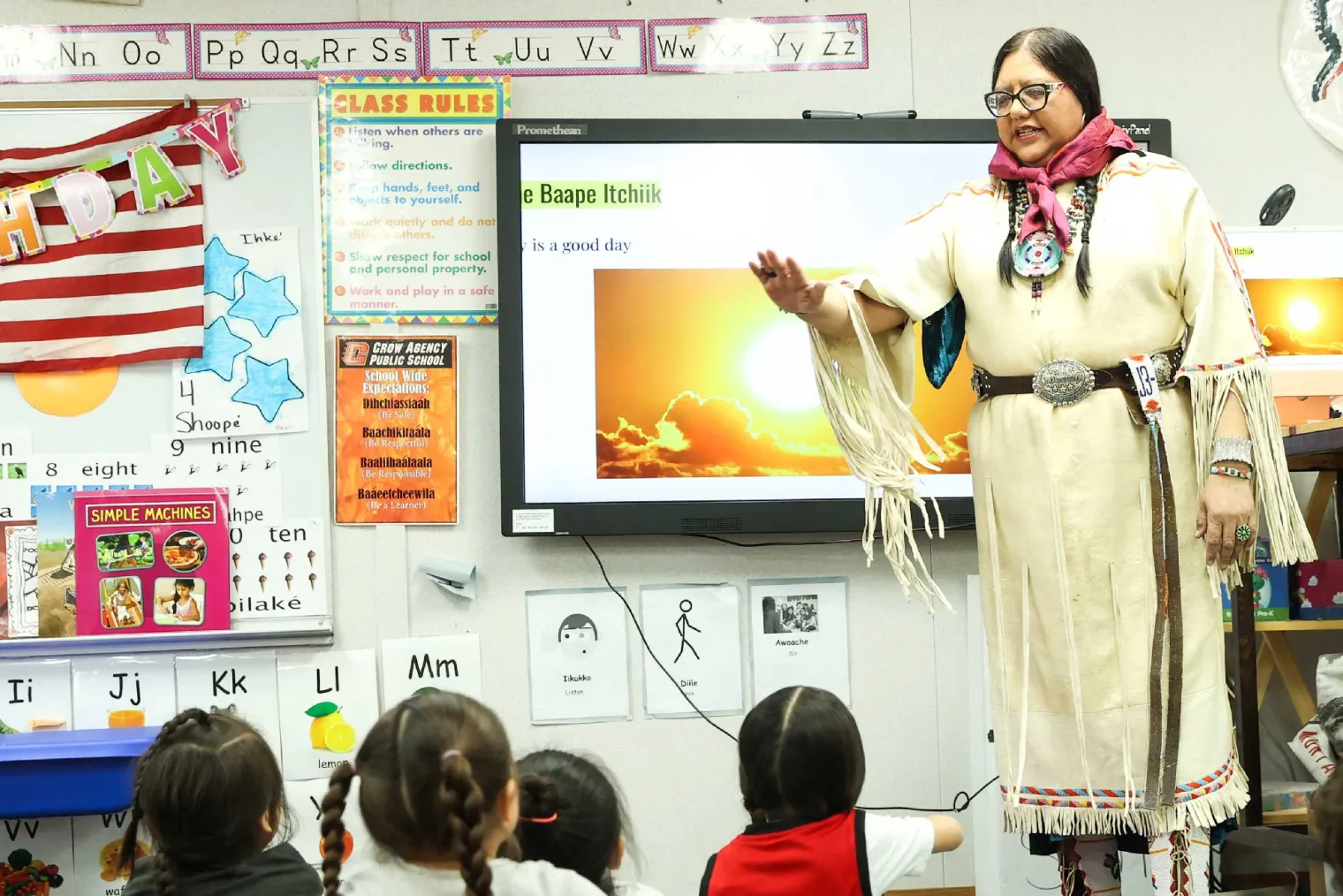

“We have to support our knowledge keepers,” says Real Bird, an Apsáalooke (Crow) language teacher on the Crow reservation, referring to those who hold and protect deep cultural and spiritual information. “They are the ones who hold our histories, our languages, and our wisdom. It’s time to honor them and build pathways for future generations to carry that knowledge forward.”

Before launching the tour, Real Bird took time to reflect on her experiences as an Indigenous person, navigating an educational system that often overlooks Indigenous cultures and the needs of her community.

A personal mission

Her story began at the Crow Agency school where she teaches. She became troubled by a pervasive issue: Lateral violence—bullying within Indigenous communities. Rooted in historical trauma, this behavior arises when long oppressed individuals redirect fear and frustration toward their own community members, Real Bird explains.

“It’s usually our own people who are against us,” she says. “We’re like crabs in a bucket. Whenever someone does good, others try to bring them down. I knew I had to do something.”

She reached out to Amanda Curtis, president of MFPE, who recognized the significance of Real Bird’s concerns and connected her with the National Indian Education Association (NIEA). This was the first step in what became a transformational experience.

A call for decolonization

At the 2022 NIEA annual conference in Oklahoma City, Real Bird heard Indigenous education scholar Cornel Pewewardy speak. The co-editor of Unsettling Settler-Colonial Education: The Transformational Indigenous Praxis Model, Pewewardy advocated for school systems designed around Native knowledge, languages, and culturally relevant teaching methods, rather than settler-centric curricula that often erase or misrepresent Indigenous cultures.

Pewewardy’s message about promoting equity, inclusion, and healing struck a deep chord with Real Bird.

“I realized that our people needed to hear this,” she says. “We needed to understand that the trauma we’re experiencing is not just personal, it’s collective. It’s been passed down from generation to generation. But we can heal, and we can do it together.”

Inspired, Real Bird returned to Montana and worked with Curtis to secure an NEA Community Advocacy and Partnership Engagement grant to conduct a series of professional development events that would share this vision across the state.

Pewewardy led discussions at each event site and explored the relationship between education and Indigenous identity in Montana.

Cultural revitalization in action

Decolonization is the process of reclaiming cultural identity, traditions, and autonomy after colonial disruption. This effort is thriving on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, in Browning, Mont.

A language immersion program in the reservation’s schools is a shining example of success under Montana’s Indian Education for All law, which mandates the inclusion of Indigenous heritage in public school curricula.

The program allows K–12 students to learn academic subjects in the Ămsskăapiipiikŭni (Blackfeet) language, preserving the language and embedding cultural relevance into education.

Ămsskăapiipiikŭni educator

Dana Bremner is president of the Browning Federation of Teachers and a reading interventionist at Stamiksiitsiikin (Bullshoe) Elementary School. She explains that the program’s goal is to integrate traditional Indigenous knowledge systems into mainstream education.

“We need to give educators the freedom to teach in a way that reflects Indigenous cultures,” she says. “Why should we teach from a curriculum designed for someone else’s worldview? We need to create our own curriculum models … [and] restore our cultural knowledge, family stories, and teach our kids who they are.”

—Brenda Álvarez

Hear the Importance Behind Lucy Real Bird's Work

Elapsed time: 0:00

Total time: 0:00Quote byLucy Real Bird

Who is Lucy Real Bird?

Lucy Real Bird is an Apsáalooke educator, cultural advocate, and proud bearer of her family’s rich heritage.

“There are so many misconceptions about who we are as Indigenous people,” she says. “Sometimes, people think we’re all Navajo because they’ve met one or two people. But we have our own identities … and stories. It’s time we tell them ourselves.”

Named Baachuaiigaalaakoosh (Sees Many Berry Seasons), Real Bird’s name was gifted by her great-grandmother, reflecting a legacy of resilience and abundance. Her father, Henry Real Bird, a celebrated cowboy poet and Montana’s Poet Laureate from 2009 – 2011, was raised by his grandfather, Xaxxe Askinneesh (Rides Painted Horses), or Mark Real Bird, and his grandmother, Baauhtah (Attends Things), or Florence Medicine Tell Real Bird. Mark Real Bird is a son of Chief Medicine Crow, and Florence is the daughter of Chief Medicine Tail.

Lucy Real Bird’s lineage is deeply rooted in her people’s history. Her maternal ancestry connects her to Chief Grey Bull and Sitting Bull, and she is a member of the Piegan Clan. They are known for their treacherousness like their enemy the Piegan (different from the Piegan Clan), made up of the Pikuni (Blackfoot), Kainai (Blood), and Siksika. As a child of the Big Lodge Clan through her father, Real Bird embrace the values and traditions passed down through generations.

Who is Lucy Real Bird?

Education News Relevant to You

Get more from