Key Takeaways

- Bob Chanin, NEA's pioneering general counsel who served public educators for four decades, passed away in May 2025.

- Chanin argued five cases and filed another 25 amicus briefs before the U.S. Supreme Court, and was a champion of civil rights and racial and social justice.

- Known as "the teacher's lawyer," Chanin spearheaded collective bargaining laws for educators, helping NEA evolve from a policy organization into a powerful union advocating for public school staff.

It was a tough young lawyer from Brooklyn who helped make NEA the strongest voice for public school education in America.

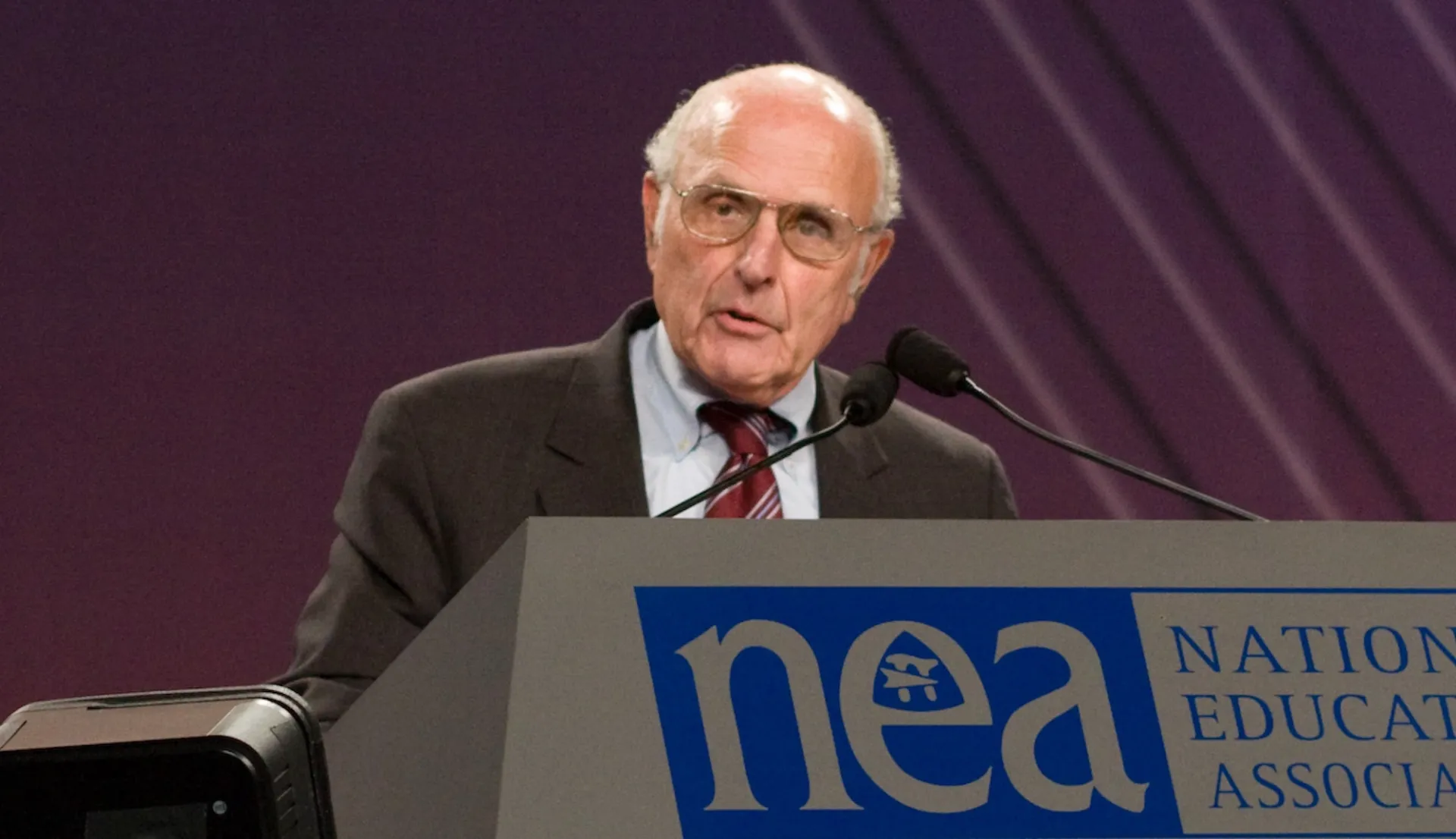

The career of Robert (Bob) Chanin as NEA’s general counsel spanned four decades, from 1968 to 2009, which were among the most volatile periods in the organization’s history. He argued five cases (winning four) and filed another 25 amicus briefs before the U.S. Supreme Court. He also acted as a fierce and tireless labor lawyer and civil rights attorney in federal and state courts across the country.

As a result of Chanin’s work, pregnant school staff can remain in their jobs without being forced to quit when they “show;” educators can teach without discrimination regardless of sexual orientation; and students have protections against harassment and other violations of their rights.

Chanin was also pivotal in transforming NEA from a professional organization focused solely on policy to a union dedicated to advocacy to improve educator pay and working conditions.

Born in Brooklyn on December 24, 1934, Chanin passed away on May 18, 2025, at 90 years old. He and his wife Rhoda, who he married in 1957, had three children and five grandchildren.

The Teacher’s Lawyer

Chanin earned his bachelor’s degree from Brooklyn College in 1956 and entered Yale Law School on a full scholarship. While there, he taught psychology at New Haven College. Upon graduation in 1959, he became a staff attorney at Columbia Law School while pursuing a master’s degree in psychology at Columbia University, which he completed in 1961.

Chanin was a new attorney with the New York firm Kaye Scholer in 1962 when it agreed to represent NEA in pursuing collective bargaining rights for its members.

Chanin asked to be on the team that would work with the new client and began his storied career as the “teacher’s lawyer.”

After meeting personally with educators around the country, Chanin learned firsthand about the myriad challenges of the profession.

He discovered that teachers entered and stayed in the classroom because of their commitment to education and the young people in their communities, but they took on the responsibility of their students’ academic training and social and emotional well-being with very few resources to support them.

Most had to take on second jobs and pay for classroom materials out of their own pockets. They had students with wildly varying abilities and learning styles as well as various home lives that could impact their learning. With no breaks in the school day, teachers had to do lesson planning and grading on their own time, and if they wanted additional training to build their practice and better serve students, they had to pay for it themselves.

Bringing Power to Public School Staff

When educators approached school boards with proposals to help address these problems – a practice Chanin called “collective begging” – the school boards had no obligation to comply and often did not.

He took the lead in working with NEA state affiliates to develop and enact state collective bargaining laws. It was groundbreaking work: Chanin and his colleagues were writing entirely new laws and defining what those laws meant, rather than implementing statutes already in the books.

Chanin helped draft and lobby for the enactment of state teacher bargaining laws in Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Those laws became the model for other states across the country.

After the transformational work of passing state collective bargaining laws, Chanin and his colleagues turned to negotiating collective bargaining agreements with school districts – covering everything from wages, hours, and working conditions to class sizes and curriculum decisions.

For the first time, teachers sat across the table from the school board, with an authentic, protected voice in decision-making.

Chanin quickly gained a reputation as a powerhouse negotiator and was known nationally as “the teacher’s lawyer,” but he also acted as organizer, strategist, and publicist for the educators’ cause.

Recognized as the expert on public teacher collective bargaining, Chanin crisscrossed the country to advocate for their rights.

He kept notes during negotiations, carefully recording administrators’ arguments that teachers didn’t deserve higher salaries because they only work until 3:00 p.m. or were mostly wives simply supplementing their breadwinner husbands’ salaries. When he spoke at rallies, he’d share those notes with the gathered teachers: “Let me read to you what they think of you.”

After blazing the trail for collective bargaining in public school education and gaining almost folk-hero status among NEA members, it became clear that NEA would benefit from Chanin’s legal mind as in-house counsel.

Though it would mean moving his family to Washington, D.C., from New York City, the only home he and his wife Rhoda and their three young children had ever known, Chanin answered the call, and on March 1, 1968, at just 33 years old, he became NEA’s General Counsel.

Champion of the Constitution

Over the next 41 years, Chanin would lead NEA’s fight for educator rights and racial and social justice.

Those victories for the constitutional rights of public school educators and students still stand, even as current right-wing efforts seek to undermine them.

For example, in 1982, he wrote an amicus brief for NEA in the landmark case Plyer v. Doe defending the rights of undocumented students. The court ruled in favor of his arguments, finding that denying undocumented children access to free public education violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.

The Trump administration has sought to overturn this decision, despite the straightforward reasoning of the Court that denying access to education would deny the children equal protection under the Constitution. The court also found that the children have no control over their immigration status and that a state cannot know whether a child would one day become a citizen and contributing member of society. An education, the court ruled, plays “a pivotal role in maintaining the fabric of our society and in sustaining our political and cultural heritage: the deprivation of education takes an inestimable toll on the social economic, intellectual, and psychological well-being of the individual, and poses an obstacle to individual achievement.”

Leading the Fight Against Vouchers

Beginning in the 1990s, private school vouchers became an intense focus of Chanin’s work. As pro-voucher forces funded a nationally coordinated campaign in states across the country, Chanin followed, arguing against them before state supreme courts, federal appeals courts, and, ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court.

Chanin’s argument and NEA’s position was clear: Vouchers violate the First Amendment's Establishment Clause, which prohibits government funding of religious institutions. They alsoundermine the public education system by potentially creating a two-tiered system where public schools are underfunded and private schools benefit from taxpayer dollars.

“Every child, not just a chosen few thousand, is entitled to a quality education. And that goal can be achieved not by abandoning public education, but only by working within the system…,” Chanin told the Wisconsin Supreme Court in 1998.

He acknowledged the many problems facing education, but stated to the court that “our challenge is to solve those problems with solutions that comport with fundamental constitutional principles…if we compromise these principles to solve a crisis in the short run, we pay a terrible price in the long run.”

He would take his argument all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 2002, and though the Court upheld the use of public money for religious school tuition, Chanin knew that the decision would not sway public opinion that vouchers are harmful to schools and communities.

''The public mindset won't change,'' Chanin told the New York Times.

Indeed, when vouchers appear on ballots, voters usually reject them, most recently in Colorado, Kentucky, and Nebraska.

But as Chanin also predicted, attacks on public education and NEA would continue. In his farewell address to the 2009 NEA Representative Assembly (RA), an annual meeting where he’d become a cult-like hero to delegates over the years for his encyclopedic knowledge of the union’s bylaws, standing rules, resolutions, and national labor law, Chanin explained that “NEA and its affiliates will continue to be attacked by conservatives and right-wing groups as long we continue to be effective advocates for public education, for education employees, and for human and civil rights.”

The reason for NEA’s effective advocacy, he said, lies in its union power, which is 3 million members strong.

In response, the 9,000 delegates in attendance at the RA in San Diego rose to their feet in thunderous applause. It was one of many standing ovations Chanin would receive during his address.

Five months later, after sorting through 41 years of legal files and packing up his office, Chanin would give one more speech in his capacity as NEA General Counsel. This time it would be in the newly minted Robert H. Chanin auditorium at NEA’s headquarters in Washington, D.C.

“I am aware of no other organization that has done more for the people it represents,” Chanin told the 187 members of NEA’s Board of Directors and other NEA leaders. “Surely there is no other labor union that has taken so principled a position in terms of civil liberties, equal rights, and social justice. What sustains me in the final analysis is the hope that NEA can do as much for public education and education employees in the next few decades as it has done in the last few decades. If you can…the world will be a little better place in which to live, and you will have the satisfaction of knowing that you did make a difference.”