Key Takeaways

- Recent gains in teacher pay have helped many districts address teacher retention. But salaries need to improve more to help attract new educators.

- Major salary increases in Charleston, South Carolina have led to a significant drop in teacher vacancies and a notable boost in morale.

- “Teachers feel valued and respected when they are paid well," said one educator.

Ten years ago, South Carolina was hemorrhaging teachers. “We couldn’t find anyone.

Teachers were leaving midyear, and hiring subs was difficult,” recalls Sherry East, who served as president of The South Carolina Education Association (The SCEA) from 2018 – 2025.

The state reported more than 1,600 teacher vacancies in the 2023 – 2024 school year—a huge increase from pre-pandemic numbers. But South Carolina may—may—have turned a corner. As the 2024 – 2025 school year began, vacancies dropped 35 percent.

“Teacher salaries have increased and most certainly helped drive down vacancies,” East says. “In many districts, pay rose quite substantially.”

According to the 2025 NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark report, South Carolina ranks 30th nationally in starting teacher salary and 36th in average teacher salary. The state has slowly but steadily climbed the rankings every year since 2020, when it stood at No. 42.

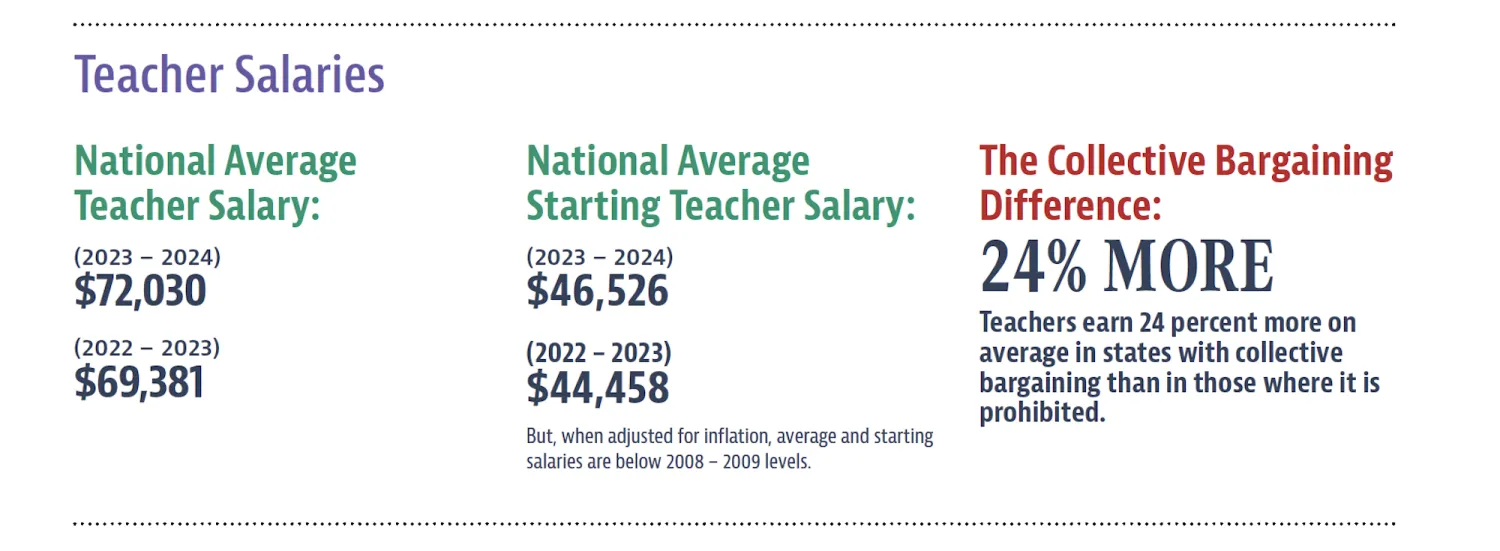

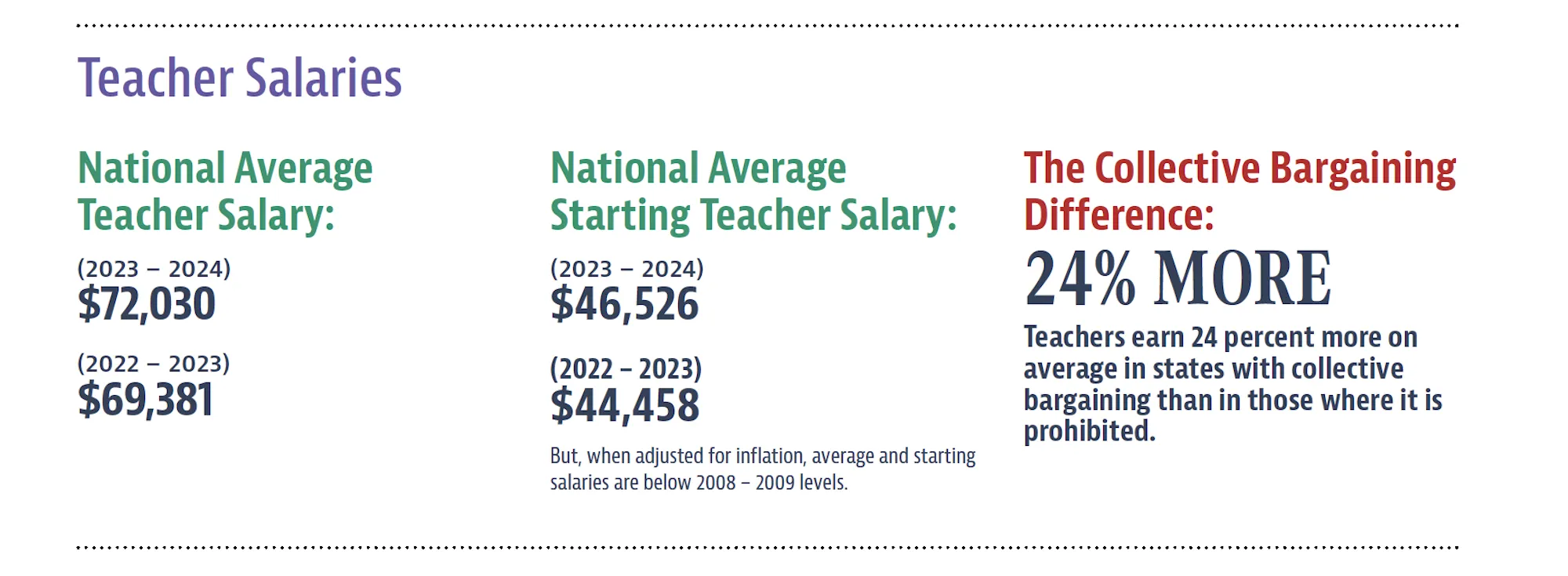

Across the country, teacher salaries are heading in the right direction. During the 2023 – 2024 school year, teachers received the most significant year-over-year pay increase in more than a decade. But even with record-level increases in some states, average teacher pay has failed to keep up with inflation.

Adjusted for inflation, teachers are making an average of 5 percent less than they did 10 years ago.

Still, Eric Burress, a fine arts teacher in Sumter County, says the impact on educators in South Carolina is real.

“When I started teaching in 2015, I had a mortgage, car payments, and everything else that comes with life,” he says. “Ten years later, is it easier? Yes. Have we been able to retain more teachers? Yes. Could it be better? Yes. But now I have my head above water. I can finally breathe. And that’s something.”

‘Treat Me like a Professional’

Burress entered the teaching profession in 2015, knowing he would take a pay cut from his earlier job and that teaching in a Title I school, like Sumter High School (his alma mater), would bring its share of challenges. But Burress has deep roots in the community and a profound appreciation for the impact his teachers had on him. “[This was] where I needed to be,” he says.

That may sound like a “calling,” but this well-intentioned term can be problematic. Too often it provides an excuse to avoid paying educators what they need and deserve. Burress loves his school, his colleagues, and his students, but even with the recent pay increase, the district will continue to face recruitment challenges, he says.

“We’ve made progress in retaining teachers, but how can we attract new teachers on the pay we’re offering—especially when adjacent districts can offer up to $10,000 more per year?” he asks. “We have to continue to do better.”

In South Carolina and across the nation, educators holding down two jobs is far more common than it should be. According to a 2024 NEA survey, 40 percent of pre-K–12 teachers had more than one job. Burress supplements his income with additional work within the school system, including teaching performing arts in the district’s program for academically gifted students.

“People will always tell you, ‘Oh, I couldn’t do your job, and you should make more,’” says East, who sold auto parts on the side for two decades.

“We tell them, ‘Well, I’ll do my job, but pay me more and treat me like a professional.’”

The Impact of Teacher Voices

Educators in states without collective bargaining can still win higher pay. Like in South Carolina, many of these states have notched up major salary wins through local or state-level advocacy.

Still, there’s no denying the union advantage. The fact is that educators who work in states with collective bargaining laws make more money. Starting salaries and top pay for teachers are higher in states where collective bargaining is legal. And teachers in 9 out of the 10 states with the highest average starting salaries were all covered by comprehensive collective bargaining laws.

Working in a state where collective bargaining is prohibited cuts off a critical mechanism for winning higher pay. So, educator advocacy in South Carolina centers around school boards and the state legislature.

And when The SCEA members tell their stories to state lawmakers and other elected officials, real change can happen, says Dena R. Crews, current president of The SCEA.

“Many lawmakers don’t really understand until they hear about our lived experiences,” she says. “We are their constituents; they represent us. So, we need to tell them about our low pay and the struggles we endure just to make ends meet. It has an impact.”

“We’ve gone from $36,000 starting salary to $48,000 in three years,” East says. “And some districts have been able to push that to more than $50,000. These are potentially life-changing jumps in pay.”

Charleston Leads the Way

Nowhere in South Carolina, and perhaps in the entire country, have these increases been more dramatic than in Charleston County. In mid-2024, the starting salary for teachers in the school district—the second largest in the state—catapulted past the state average to $56,200 and will increase this upcoming school year to $64,000. Before the raises, the district had more than 100 teacher vacancies each year. In early 2025, after the raises went into effect, the district reported a mere handful scattered across the district.

These changes did not come quickly. It all started three years ago, when Chief Human Resources Officer William Briggman announced the formation of a Teacher Compensation Task Force. His motivation? Concern about teacher recruitment and retention in the face of a meteoric rise in Charleston’s cost-of-living.

“Teachers couldn’t live here or near the communities they serve,” says Patrick Martin, a teacher at Charleston County School of the Arts and a longtime advocate for higher pay. Martin offered to serve on the task force, although he had to manage his expectations first.

“Sometimes these kinds of groups are really just about people, politicians usually, just looking for a soundbite,” Martin says.

That skepticism quickly evaporated.

Briggman put the work in,assembling a coalition of teachers, principals, businesspeople, and community members to work together on the issue. But it was those educator voices that Briggman wanted most to highlight.

“Teachers would come in and tell their stories to the school board. The district produced videos with these testimonials,” Martin recalls. “This was really key to building the relationship with the school board.”

Budget discussions centered on housing costs, instead of arbitrary dollar figures or a one-time bonus. So, the question was: What do teachers— particularly those newer to the profession—need to earn so they can live closer to where they work?

Starting in 2024, the school board began approving a series of measures boosting teacher salaries across the board. In addition to the dramatic increase in starting pay, the board also added 12 steps to the district’s pay schedule, pushing top salaries well past $100,000 from a previous limit of $81,000.

In addition to the resulting drop in staff vacancies, says Martin, the increases have led to a much-needed morale boost in Charleston County. “You can see it in classrooms, hallways, and out in the community.”

From No. 39 to No. 7

“Teachers feel respected and valued when they are paid well,” says Julie Wojtko, president of NEA-Las Cruces, in New Mexico. “The salary increases we’ve received have made a huge impact.”

By the 2023 – 2024 school year, New Mexico had moved up to 7th from 39th in the country on starting salaries, and from 49th to 21st on average salaries, according to NEA data.

Meanwhile, in Texas, where Wojtko’s sister teaches, salaries have stagnated at $10,000 below the national average.

Veteran educators are especially hard hit. “[My sister and I] both have our master’s degrees, and my sister works so hard. But I make more than her, and that’s not right,” Wojtko says.

“Texas does not have a strong, pro-public education governor.… And there is no collective bargaining. We have that in New Mexico, and it makes a difference.”

In states where pay has increased significantly, the cost of living in many of these areas can negate much of the positive benefit. Even in states that rank in the top 10 for average teacher salaries, educators and their unions continue to fight for professional pay.

According to NEA data, the average teacher salary in Connecticut is $86,511 (sixth nationwide), with an average starting salary just below $50,000.

The cost of living in the state, how - ever, is 21 percent higher than the national average.

“I know educators who make more than $70,000 and still need a second job or have two or three roommates,” says Mia Dimbo, a math teacher in Bridgeport, the largest district in the state. Dimbo says the teacher shortage in her cash-strapped district is severe.

“We’re an urban school district and are surrounded by wealthy suburbs. At my school, we can’t get certified teachers. We rely too heavily on long-term subs. We haven’t had a science teacher in five years.”

As a veteran teacher, Dimbo says she does OK, but continually worries whether new teachers will ever want to work in Bridgeport, if salaries remain inadequate. And incoming cuts to federal funding—a sizeable chunk of Bridgeport’s budget—are an added worry. “We get so much from the federal government. We already have a huge recruitment and retention problem. It’s hard to even think about,” she says.

The Next Level

In South Carolina, the next step for The SCEA is to get starting salaries up to $50,000 statewide by 2026, a goal supported by many in the state legislature. “That’s where we need to go soon, because we still have a lot of work to do to attract and keep teachers in the profession,” Crews says.

The Teacher Compensation Task Force that led the successful effort to boost salaries in Charleston has been rebranded as the Teacher Recruitment and Retention Task Force. “We’re looking at other issues, like improving working conditions and child care,” explains Martin. “And we’re sharing our story and best practices, because we need to help pull up the rest of the state as well, so that we’re not just one pocket where this is happening.”

In Sumter County, Burress is cautiously optimistic that recent increases will continue to help retain the educators the district has been able to bring in, but salaries are still not high enough to attract new people to the profession. “We’ve made progress, no question. But it’s still difficult to recruit. So, with salaries, we have to get to that next level. There’s a model we can follow in Charleston, so maybe we can catch up to them!”