For School Support Staff, Respect Begins with a Living Wage

Jonathan Ng/Massachusetts Teachers Association

Jonathan Ng/Massachusetts Teachers Association

Key Takeaways

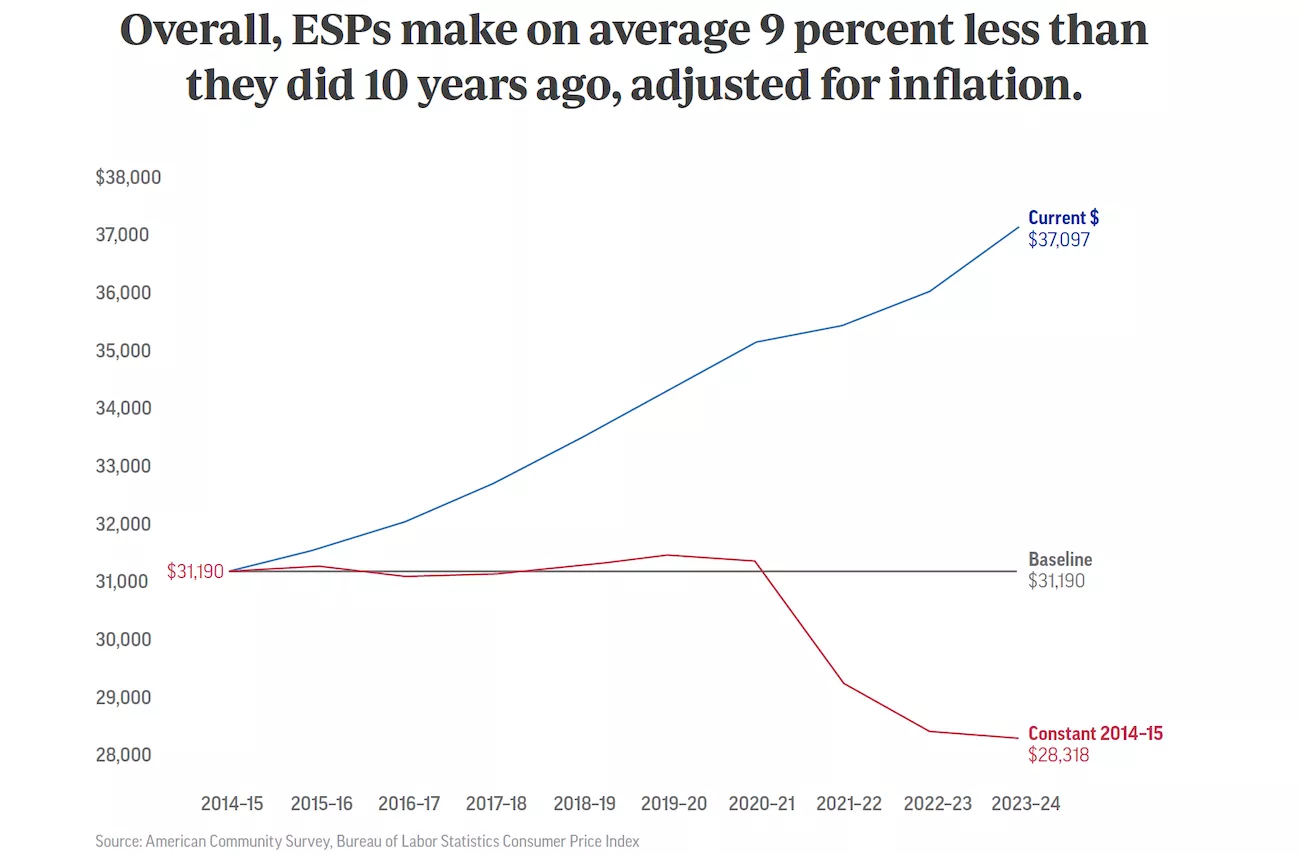

- According to a new NEA report, the average earnings for education support professionals in K-12 and higher education increased to $37,097 in 2023–2024, about a $1,000 increase over the average earnings in 2022–2023.

- Average earnings rose from $31,190 in 2014–2015 to $37,097 in 2023–2024. However, when adjusted for inflation, earnings actually fell from $31,190 to $28,318 in constant 2015 dollars.

90%

37%

Danielle Jones is a special education instructional assistant in Arlington City Schools in Virginia. She has been in her current position for seven years and has spent 21 years in education. Jones has a bachelor’s degree and is halfway to earning her master’s. She works a second job as a speech and debate coach and has a roommate—common for support staff in the district.

But some colleagues are facing even greater financial pressures. “We have people who are receiving housing assistance, we have people who are on food stamps. The pay is not just enough to make daily ends meet,” Jones says.

“We are all dedicated professionals, but it is getting difficult to bring 100 percent, especially if you have to work in another job. It’s exhausting and it leads to burnout.”

In 2024, the National Education Association surveyed school support staff, also known as education support professionals (ESP), and found that low pay is a “moderate or serious” concern for 90 percent of those who work in K-12 schools. Thirty-seven percent hold down a second job and one-third have a moderate or serious problem buying food. Many respondents also reported that they skip routine or preventative doctor appointments to avoid compounding financial strain.

Staff shortages have been widespread, especially since the pandemic, but will only worsen, Jones says, unless improvements are made. “If people can’t really survive on the low pay, the staff turnover, the shortages will only get worse. These are dedicated people, but how do continue if you’re thinking your food stamps won’t last to the end of the month?”

ESP Earnings Lagging Inflation

According to new data released this week by NEA, less than one-third (29.7 percent) of all ESPs working full-time in 2023-24 earned less than $25,000 per year, and 10 percent earned less than $15,000.

The “Education Support Professional Earnings Report” is released annually and provides a pay breakdown for school support staff working in K-12 public schools and higher education.

Of the approximately 2.2 million support staff working in K-12 public schools, 34.5 percent made less than $25,000 in 2023-24. In 2022-23, 38 percent earned less than $25,000.

Within higher education, 12.6 percent earn less than $25,000, and 6.2 percent earn less than $15,000.

The earnings report also found that the average earnings for a full-time ESP was $37,097, only a $1,000 increase over the previous year. Higher education earnings came in at $45,662, K-12 at $34,954.

For K-12 ESPs, that’s an overall increase from $31,190 in 2014-15, but, when adjusted for inflation, average earnings have declined to $28,318 in constant 2015 dollars over the past ten years.

According to the report, Rhode Island had the highest average K–12 ESP full-time earnings at $42,940. Full-time earnings was above $40,000 in eight states—Alaska, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island—and the District of Columbia.

Oklahoma had the lowest average K–12 ESP full-time earnings at $27,656. The average K–12 ESP full-time earnings was below $29,000 in five states (Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Oklahoma).

The Collective Bargaining Difference

Once again, as was evident in previous earnings reports, the “union advantage” is real.

ESPs in states with collective bargaining statutes earn on average $38,554. Those who work in states where collective bargaining is prohibited earn on average $35,879, a seven percent difference.

In 2024, bargaining power fueled a major victory for paraeducators in Andover, Massachusetts, where Karen Torres has worked as an instructional assistant for 17 years. A hard-fought new contract has lifted starting pay from $24,537 to $39,142 per year. By the end of the four-year contract, the highest paid will be earning $50,103.

Section with embed

Torres, the 2024 Massachusetts Teachers Association ESP of the Year and a key member of the Andover Education Association bargaining team, says her job has changed significantly over the years.

“When I started, the job entailed was a lot of making copies for teachers, correcting papers, watching children in the lunchroom, monitoring recess,” Torres recalls. “It has evolved immensely, and that is mostly due to increasing student needs—the academic demands and the behavioral and social emotional needs, which are nothing like they were a decade or so ago. But the compensation just has not kept up, and it’s unacceptable.”

Educator Pay in Your State

-

Alabama

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$44,610NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#31in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$61,912State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#33in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

66¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$60,531Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$13,176Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#41in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$30,776Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#40in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$42,935Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#35in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$92,342Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#34in the nation -

Alaska

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$52,451NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#9in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$78,256State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#10in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

80¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$86,128Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$20,638Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#13in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$40,588Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#9in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$44,515Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#26in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$89,364Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#39in the nation -

Arizona

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$46,128NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#23in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$62,714State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#29in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

66¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$66,744Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$11,808Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#48in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$32,374Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#29in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$45,345Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#22in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$105,188Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#17in the nation -

Arkansas

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$50,031NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#14in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$58,337State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#41in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

75¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$58,446Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$13,061Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#42in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$30,415Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#42in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$40,487Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#46in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$78,353Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#50in the nation -

California

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$58,409NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#2in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$101,084State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#1in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

80¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$69,601Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$18,969Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#17in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$41,013Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#5in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$51,110Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#3in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$133,447Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#1in the nation -

Colorado

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$42,421NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#41in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$68,647State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#20in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

62¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$68,473Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$16,889Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#21in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$35,249Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#21in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$48,471Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#11in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$99,017Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#27in the nation -

Connecticut

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$49,860NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#15in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$86,511State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#6in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

76¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$90,897Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$24,012Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#6in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$40,743Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#8in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$54,653Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#1in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$119,180Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#5in the nation -

Delaware

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$48,407NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#19in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$71,186State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#16in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

84¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$73,822Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$19,401Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#15in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$42,551Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#2in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$45,242Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#23in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$121,990Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#3in the nation -

Florida

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$48,639NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#17in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$54,875State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#50in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

76¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$61,002Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$13,584Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#39in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$33,324Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#26in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$42,681Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#37in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$107,149Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#13in the nation -

Georgia

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$43,654NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#35in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$67,641State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#23in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

73¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$60,167Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$14,546Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#31in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$31,472Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#38in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$41,096Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#44in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$95,190Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#31in the nation -

Hawaii

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$51,835NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#10in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$74,222State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#14in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

80¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$103,670Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$18,943Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#18in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$40,894Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#7in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$47,084Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#17in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$119,443Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#4in the nation -

Idaho

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$45,717NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#24in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$61,516State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#34in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

73¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$60,738Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$9,942Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#51in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$28,345Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#47in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$39,438Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#49in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$84,225Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#45in the nation -

Illinois

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$45,061NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#26in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$75,978State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#13in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

76¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$66,359Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$21,657Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#10in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$35,651Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#18in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$44,272Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#27in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$106,064Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#14in the nation -

Indiana

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$45,007NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#27in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$58,620State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#39in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

76¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$63,090Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$13,374Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#40in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$31,501Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#37in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$44,251Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#28in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$101,684Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#21in the nation -

Iowa

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$40,997NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#46in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$62,399State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#32in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

81¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$62,495Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$13,931Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#36in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$30,966Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#39in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$47,841Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#14in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$108,102Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#12in the nation -

Kansas

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$42,800NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#36in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$58,146State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#44in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

73¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$62,101Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$14,901Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#30in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$28,270Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#48in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$43,069Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#34in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$89,708Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#37in the nation -

Kentucky

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$40,161NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#48in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$58,325State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#42in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

69¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$60,408Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$14,174Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#35in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$28,088Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#49in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$41,865Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#39in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$83,327Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#47in the nation -

Louisiana

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$46,682NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#22in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$55,911State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#47in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

72¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$62,158Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$17,541Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#19in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$29,764Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#44in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$41,860Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#40in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$79,520Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#49in the nation -

Maine

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$42,380NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#42in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$62,570State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#30in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

79¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$71,296Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$22,153Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#8in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$31,708Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#35in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$43,371Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#33in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$92,904Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#33in the nation -

Maryland

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$54,439NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#6in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$84,338State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#7in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

73¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$64,242Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$19,345Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#26in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$38,613Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#11in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$46,467Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#19in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$115,268Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#6in the nation -

Massachusetts

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$52,616NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#8in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$92,076State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#3in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

77¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$79,117Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$26,123Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#4in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$37,876Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#13in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$50,558Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#4in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$109,142Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#11in the nation -

Michigan

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$41,645NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#44in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$69,067State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#19in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

71¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$62,245Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$14,489Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#32in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$31,753Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#33in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$48,156Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#12in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$112,298Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#7in the nation -

Minnesota

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$44,995NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#28in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$72,430State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#15in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

67¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$64,701Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$16,593Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#24in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$35,938Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#16in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$47,933Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#13in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$104,351Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#20in the nation -

Mississippi

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$42,492NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#40in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$53,704State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#51in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

84¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$62,865Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$12,490Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#45in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$27,741Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#50in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$38,146Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#50in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$78,015Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#51in the nation -

Missouri

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$38,871NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#49in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$55,132State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#49in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

67¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$57,382Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$13,586Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#38in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$31,711Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#34in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$44,201Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#29in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$89,443Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#38in the nation -

Montana

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$35,674NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#51in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$57,556State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#45in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

77¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$67,948Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$14,480Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#33in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$32,037Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#30in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$41,360Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#42in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$84,296Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#44in the nation -

Nebraska

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$38,811NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#50in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$60,239State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#37in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

76¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$65,822Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$15,896Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#26in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$30,408Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#43in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$45,151Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#24in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$95,837Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#30in the nation -

Nevada

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$47,355NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#20in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$66,930State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#25in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

80¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$70,917Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$11,927Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#47in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$39,327Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#10in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$48,808Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#8in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$105,568Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#15in the nation -

New Hampshire

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$42,588NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#38in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$67,170State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#24in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

68¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$79,021Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$22,252Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#7in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$32,762Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#28in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$41,709Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#41in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$100,947Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#24in the nation -

New Jersey

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$57,603NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#4in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$82,877State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#8in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

87¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$85,129Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$24,831Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#5in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$42,233Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#3in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$52,064Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#2in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$129,661Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#2in the nation -

New Mexico

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$53,400NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#7in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$68,440State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#21in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

83¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$67,411Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$15,183Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#29in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$29,457Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#45in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$42,788Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#36in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$91,094Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#36in the nation -

New York

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$50,077NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#13in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$95,615State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#2in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

83¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2024Minimum Living Wage

$71,455Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$31,514Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#1in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$40,939Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#6in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$49,143Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#7in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$104,460Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#19in the nation -

North Carolina

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$42,542NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#39in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$58,292State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#43in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

75¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$58,411Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$13,796Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#37in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$31,686Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#36in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$43,765Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#31in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$98,421Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#28in the nation -

North Dakota

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$43,734NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#34in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$58,581State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#40in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

80¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$62,610Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$17,492Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#20in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$35,259Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#20in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$47,671Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#15in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$86,852Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#42in the nation -

Ohio

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$40,982NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#47in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$68,236State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 202#22in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

83¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$61,682Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$15,436Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#28in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$35,775Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#17in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$47,636Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#16in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$101,619Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#22in the nation -

Oklahoma

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$41,152NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#45in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$61,330State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#35in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

67¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$60,423Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$11,311Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#49in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$27,656Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#51in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$39,785Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#48in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$88,372Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#41in the nation -

Oregon

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$44,446NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#33in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$77,130State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#11in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

71¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$76,602Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$16,760Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#23in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$34,656Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#23in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$46,023Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#20in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$100,734Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#25in the nation -

Pennsylvania

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$50,470NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#11in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$76,961State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#12in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

81¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$58,542Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$20,779Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#12in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$36,869Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#15in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$45,562Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#21in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$104,820Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#18in the nation -

Rhode Island

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$47,205NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#21in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$82,189State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#9in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

90¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$85,000Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$21,794Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#9in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$42,940Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#1in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$49,221Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#6in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$105,299Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#16in the nation -

South Carolina

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$44,693NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#30in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$60,763State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#36in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

86¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$60,284Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$14,306Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#34in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$31,800Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#32in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$44,766Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#25in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$94,872Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#32in the nation -

South Dakota

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$45,530NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#25in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$56,328State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#46in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

84¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$64,086Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$12,956Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#43in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$30,618Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#41in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$35,815Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#51in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$84,406Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#43in the nation -

Tennessee

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$44,897NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#29in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$58,630State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#38in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

72¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$58,440Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$12,616Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#44in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$29,362Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#46in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$40,297Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#47in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$92,121Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#35in the nation -

Texas

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$48,526NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#18in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$62,463State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#31in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

77¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$58,033Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$12,423Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#46in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$31,812Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#31in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$44,198Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#30in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$101,189Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#23in the nation -

Utah

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$55,711NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#5in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$69,161State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#18in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

70¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$68,293Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$11,289Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#50in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$37,437Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#14in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$41,177Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#43in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$112,057Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#8in the nation -

Vermont

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$44,524NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#32in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$69,562State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#17in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

87¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$117,218Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$28,697Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#2in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$35,071Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#22in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$40,544Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#45in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$88,475Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#40in the nation -

Virginia

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$48,666NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#16in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$66,327State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#26in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

67¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$61,250Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$16,832Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#22in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$34,490Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#24in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$46,705Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#18in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$112,022Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#9in the nation -

Washington

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$57,912NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#3in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$91,720State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#4in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

72¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$67,332Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$19,955Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#14in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$38,609Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#12in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$49,875Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#5in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$110,332Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#10in the nation -

Washington, D.C.

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$63,373NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#1in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$86,663State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#5in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

81¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$101,008Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$27,905Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#3in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$41,097Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#4in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$48,520Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#10in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$83,630Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#46in the nation -

West Virginia

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$42,708NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#37in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$55,516State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#48in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

79¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$64,800Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$15,797Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#27in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$33,247Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#27in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$43,414Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#32in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$80,874Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#48in the nation -

Wisconsin

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$42,259NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#43in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$65,762State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#27in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

75¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$67,853Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$16,285Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#25in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$35,577Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#19in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$48,568Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#9in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$99,102Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#26in the nation -

Wyoming

Average Teacher Starting Salary

$50,214NEA Teacher Salary Benchmark Report, FY 2023-24, April 2025#12in the nationAverage Teacher Salary

$63,669State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#28in the nationTeacher Pay Gap

89¢Compared to other college-educated professionals with similar experience. Economic Policy Institute, September 2025Minimum Living Wage

$71,181Income needed for family of one adult and one child to have a modest but adequate standard of living in the most affordable metro area, 2024 dollars, Economic Policy InstitutePer Student Spending

$20,869Expenditure per student in fall enrollment. State Rankings, FY 2023-24, NEA Rankings & Estimates Report, April 2025#11in the nationAverage K-12 ESP Earnings

$33,676Average K-12 ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#25in the nationAverage HE ESP Earnings

$41,936Average Higher Education ESP Earnings, FY 2023-24, NEA Education Support Professional Earnings Report, April 2025#38in the nationAverage Higher Ed Faculty Salary

$97,591Average Faculty Salary for Four-Year Public Institutions, FY 2023-24, NEA Higher Education Faculty Salary Analysis, April 2025#29in the nation

‘Show us That Respect’

A living wage is one of the central pillars of the national ESP Bill of Rights campaign, recently introduced by NEA. The campaign is calling on lawmakers to invest in school support staff and outlines the top 10 most pressing concerns of ESPs. Along with a living wage, these include adequate health coverage, paid leave, professional training and education, and a safe and healthy work environment. In addition to Massachusetts and Virginia, local and state unions have launched bill of rights campaigns in 12 other states, including Maryland, Illinois, Vermont, Michigan, and Washington.

Vermont bus driver Jimmy Johnson helped create Vermont-NEA’s Educators’ Bill of Rights, which members approved at their 2024 representative assembly, and carved out provisions specifically for support staff, including a minimum starting rate of $30 per hour. “We all want a better life,” Johnson recently told NEA Today.

Quote byKaren Torres, Instructional Assistant, Andover, Mass.

Both Torres and Jones have been instrumental in their respective states’ campaigns.

In her advocacy, Torres says she is often struck by peoples’ reactions when they’re informed about the low pay, lack of benefits and challenging working conditions ESPs endure.

“It's mind-blowing to people. So when you get the word out there in the community, when you tell your story, it should help getting districts and school boards to sign off on the bill of rights. We’re working very hard in getting politicians and elected officials to stand behind us on this,” says Torres.

First, it starts with a living wage, says Jones. “There are so many things that need to change, but the sincerest form of appreciation is to compensate us justly, and then other things will follow that. Our work on other issues doesn't end. But pay us what we are worth, show us that respect.”

Related Content

Tim Walker

Senior Writer/Editor