Fewer than half of the cells in our bodies are human cells.

That’s the kind of fun fact that science teacher Samuel Washington Jr. loves to drop on his students at the start of the school year. He’ll also have his biology students design “weird but true” bumper stickers. Things like, the human stomach can dissolve razor blades, a cloud can weigh more than a million pounds, and hot water can freeze faster than cold water. And if you’re still wondering, the rest of the human body is made up of trillions of non-human microbial cells, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses!

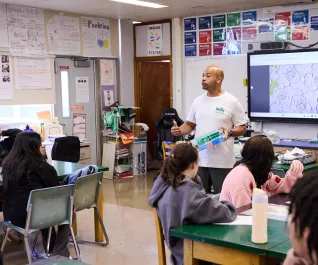

Washington has taught for more than three decades and knows science can lose its spark if it’s reduced to textbooks and note-taking.

Quote bySamuel Washington Jr., who teaches at Woodlands High School, in Hartsdale, N.Y.

He also uses science to meet students where they are and draw them into learning through wonder and relevance.

The need to ‘be better’

Men of color make up just 2 percent of educators nationwide, so Washington sees representation as central to his work.

“Growing up I didn’t see a lot of me in my own teachers,” he says. “That really inspired me to go just a little harder in terms of what I bring to the table … to be better.”

Today, that commitment translates to setting high expectations for himself and his students.

“I don’t have time to slack off because I want [my students] to be the best they can be,” Washington says. “I’ll say, ‘I know sometimes you don’t want to be here, sometimes I don’t want to be here—we’re human. But if you can give me your best, I’ll give you my best.’ And that’s all I can ask for.”

Holding students to high standards goes hand in hand with creating a classroom where they feel seen and valued.

Washington makes sure his students feel like they belong in school. For example, during Hispanic Heritage Month, Black History Month, and Women’s History Month, he asks students to research scientists whose names don’t appear in the usual textbooks.

And when one of his students was allowed to profile her mother, a hospital worker, her grades started improving.

“She was like, wow, he really does care about what I have to offer and where I come from,” Washington recalls.

He adds: “Not only am I beneficial to students of color, especially young Black males, but I feel I’m a benefit to all students.”

A bond beyond the classroom

Some of Washington’s most powerful connections stretch across years. He recalls one ninth grader who entered his honors biology class nervous and unsure—both about her own abilities and about Washington’s, since he was a newer teacher at

the time.

By the end of her senior year, she had taken every course he offered and later went on to Harvard. Her younger brother followed the same path.

Recognition, he admits, is gratifying. But what means the most to Washington is how his lessons in science continue to resonate years later.

“Sometimes, as a teacher, the impact of our work can go under the radar until years after a student has graduated,” he says. “I’ve had former students come back after 20 years to thank me for how much I did to prepare them for life after high school. To be honored in real-time makes it come alive.”

Washington share his love of science in his own words

Who is Samuel Washington Jr.?

“[My friends and I] always joke that we were bowling alley kids,” says Washington, whose father was an avid bowler. His last memory with his dad, who died when Washington was 16, was winning a tournament together.

That moment inspired him to coach, mentor, and guide young people through a school bowling program. Over the years, his youth league and high school teams have earned championship titles and collected thousands in scholarship money—extra support that helped many students pursue college.

“I’ve found that students who bowl, or who are in clubs, perform a little bit better in school,” Washington says. “They know someone cares about them, and that makes all the difference.”

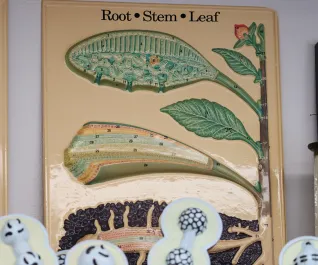

A Look Inside Mr. Washington's Classroom

Shea Kastriner

Shea Kastriner

Shea Kastriner

Shea Kastriner

Shea Kastriner

Shea Kastriner