Key Takeaways

- The first step? Stop seeing boys as problems in your classrooms, say male teachers and experts.

- The second step: Focus on modeling "help-seeking behaviors" that counter stereotypes about what it means to be a typical boy or man.

- Additionally, work on creating opportunities for boys to spend time with each other, building community. Extra-curricular clubs are a great idea!

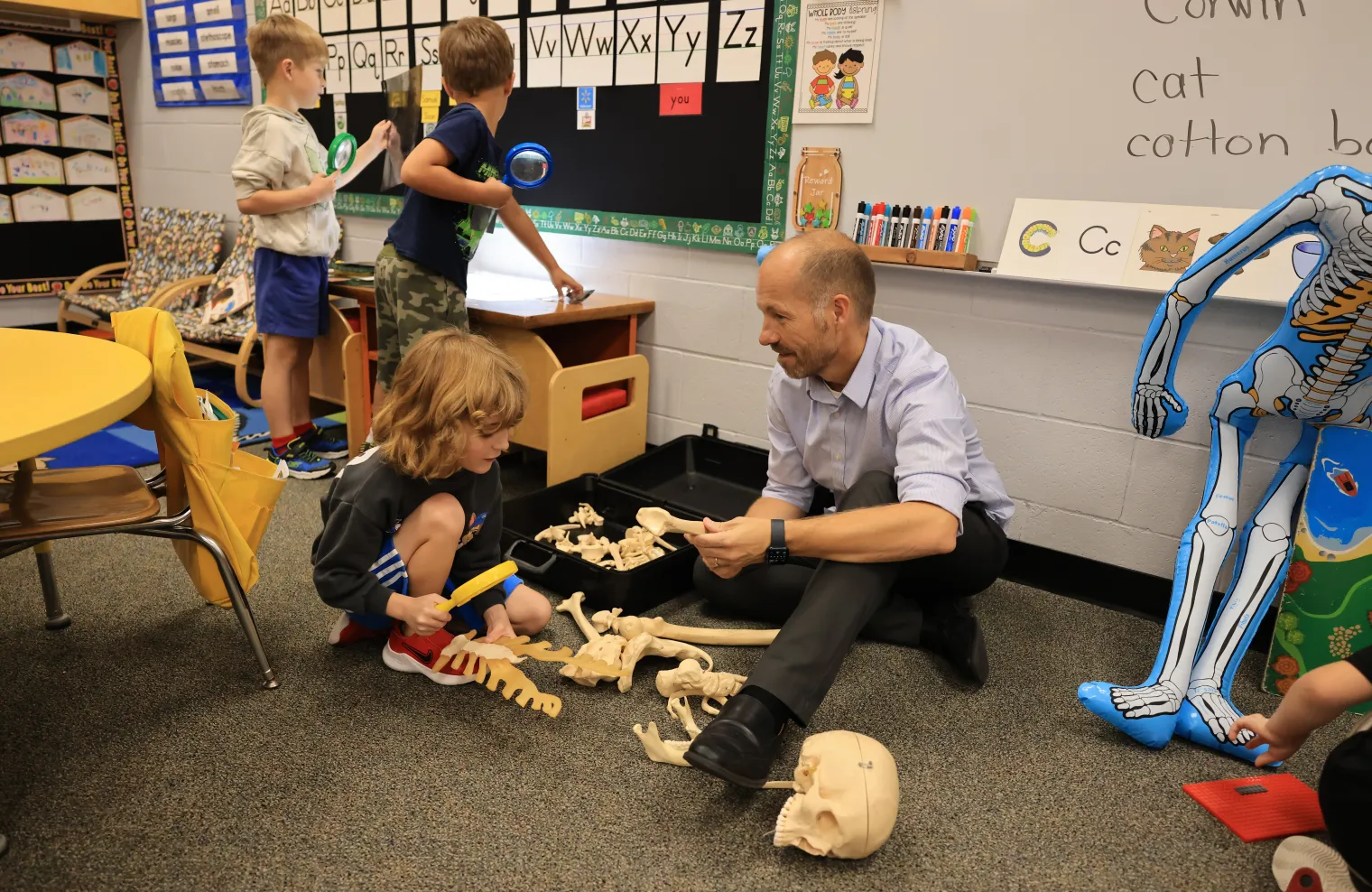

During kindergarten labs, Samuel grabs a bright red, toy ear scope. “Mr. Taylor! Mr. Taylor!” he says urgently. Dwayne Taylor sits, tilts his head obligingly for his exam, and Samuel peers into the brain of the meanest teacher in the school.

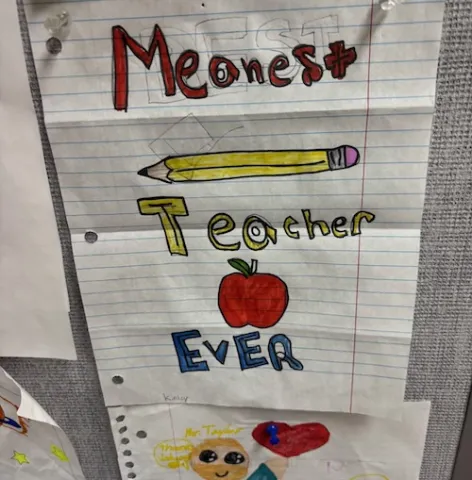

“Ha! That’s Mr. Taylor’s favorite joke!” says Owen Glynn, a third grader at Frank Layden Elementary School, in Frontenac, Kan., who had Taylor for kindergarten and still pops by to say hi. “Mr. Taylor always says he’s the meanest teacher in the school, but he’s really the nicest!”

By “nicest,” Owen means Taylor is a pro at cultivating connections with students. He tells his kindergartners he loves them. He talks about his own feelings: “I am so happy to see you,” or “I am feeling really frustrated right now.” And he helps his 5-year-olds find words for their feelings, too.

Taylor is aware of what pundits are calling the “boy crisis” in U.S. schools. Every day, he lays the foundation so his little ones can climb higher. In his classroom, he models how to ask for help, how to be vulnerable, how to be a friend and work in teams, and how to succeed in school and life. “Oh hey, what do I say? Teamwork is … ” Taylor prompts. “Dream work!” his class sings back to him.

Good morning, Mr. Taylor!

Elapsed time: 0:00

Total time: 0:00Quiz time!

Who are more likely to be suspended or expelled from school, boys or girls?

Answer: Boys. (It starts early: Preschool boys are five times more likely to be expelled than girls. According to federal data, Black boys account for half of all expulsions, even as they account for 20 percent of preschoolers.)

Who are less likely to take advanced placement classes?

Boys.

Less likely to go to college?

Boys, by a mile, and the gap is getting wider.

More likely to suffer loneliness?

Boys. (One in 4 say they have no close friends. That’s a five-fold increase since 1990, with higher rates of disconnect among Black men and Black boys.)

More likely to die by suicide?

Teen boys. In fact, they are about three times more likely to die by suicide than teen girls. The situation has become so dire that California Gov. Gavin Newsom issued an executive order a few months ago to address boy’s suicide rates, reduce stigma, and expand access to work and mentorship opportunities.

“It is a crisis of connection,” wrote Richard Reeves, founding president of the American Institute of Boys and Men, in a New York Times op-ed.

More male teachers would help, Reeves suggests, as would more apprenticeships and more male-friendly mental health services. “Doing more for boys does not mean doing less for girls,” he notes. “As all the politicians leading on this issue correctly insist, gender equality is not a zero-sum game. We can do two things at once. We can take better care of girls and boys.”

Back in Taylor’s kindergarten classroom, sous chef Bennett is eager to participate in today’s cooking lesson, cracking eggs like he’s on Cake Boss. Taylor’s boys laugh. They learn. They share. They care. And they giggle happily to learn that the largest muscle in the human body is … the gluteus maximus!

Scenes from Mr. Taylor's Classroom

Rethinking Stereotypes

When Carlos Grant first became a high school principal in South Carolina six years ago, the student data that crossed his desk was alarming. “Our drop-out data, our discipline data, our college readiness data, all of it showed that our boys—all of our boys, but especially Black boys—weren’t keeping up,” he recalls.

His answer? “We began a concerted effort to talk about our relationships with boys, and it really changed the trajectory for many of them,” he recalls. “We had to unlearn a mindset about boys.”

The first step to reversing “problems with boys” is to stop seeing them as problems, says Joseph Derrick Nelson, an associate professor of educational and Black studies at Swarthmore College. “Don’t see them as a problem to be managed but as a child with the same hopes and dreams as all youth.”

There are prevailing ways of thinking about boys, which sound old-fashioned, but persist today. “Boys don’t cry. Hold your head up. Be strong,” Grant reels them off. “Don’t show fear. Don’t show weakness.” In classrooms, this may translate to: Don’t ask for help. Be strong. Stay silent.

Most kindergartners haven’t internalized these messages yet, notes Nelson. At young ages, boys are equally curious, joyful, relational, and warm. But by middle school and high school? “The older they get,” he says, “the more they internalize these norms and the harder they are to undo.”

Meanwhile, educators may have their own internal biases—boys are lazy, boys need discipline, and so on—that lead to unequal support and discipline, Grant notes.

“Boys aren’t given grace. They’re written up, they’re labeled more quickly, and because of that, there’s a self-narrative that exists. The more you tell somebody they’re ‘this way,’ the more they’re going to act ‘that way,’” he says.

A key lesson for Grant and his colleagues: Stop backing boys into corners. “If I’m correcting a boy in my classroom and I’m doing it in a way that’s embarrassing to him, that’s devastating to him, and he decides to lash out to save face, to save his pride and dignity? Well, that’s my fault, as an adult,” Grant says. “I put him into that corner. I made a bad situation worse.”

It’s also important to know that acting out can be a sign of mental health struggles, rather than “boys being boys,” says New York school psychologist Peter Faustino. For example, he says, “With depression, you might see boys become aggressive. It’s easy to misinterpret those symptoms.”

How Do You Talk About Feelings?

Elapsed time: 0:00

Total time: 0:00Teaching boys how to seek help

Outside Taylor’s classroom door, he greets every kindergartner with a hug, high-five, handshake, or no contact. It’s their choice, made by smacking a paper icon.

“Oh, you’re coming in for the hug!” he says. His message to every child is clear: “CJ, I’m so glad you’re here today. … I’m super glad you’re here today, Tytan. … Come on in, dude, I’m so glad you’re here today!”

After indoor recess, thanks to pouring rain, Taylor’s kindergartners are a bundle of chaos in the halls. There is mayhem by the water fountain. When they return to class, Taylor is frustrated and he tells them so, calmly but firmly.

“Am I going to let what happened ruin my day?” he asks. “Nooo,” they tell him. “Can I do it myself?” “Nooo,” they say. To turn around his day—to get back to the “green zone,” as Taylor calls it—he tells them he needs their help.

In Grant’s work with older students and mentees, he also models “help-seeking behavior,” as Faustino calls it. “One of the struggles young men deal with is their reluctance to ask for help,” Grant says. “You have to model vulnerability. You have to show what it’s like not to be okay—and that that’s OK.”

Grant tells the teens in Alpha GENTS, his fraternity’s mentoring program: “I might look like I have it together but, buddy, … none of us have it all together.’”

Taylor says, “I tell my kids every day: There’s nothing you could do to make me stop loving you. You might make me lose the rest of my hair! But I will never stop loving you.”

What Works: Relational Teaching With Boys

Create Community With Clubs

“Girls participate in everything compared to boys,” says Johny Sozi, a Maryland computer science teacher. “You even see the difference at lunch—girls go in big groups!” One way to counter boys’ isolation? Create clubs that provide community for them. (When possible, make sure to tap into salary bonuses negotiated by your union for club or team advisors!)

Go fishing!

This fall, middle school teacher Jace Brescher had 86 students at his fishing club’s interest meeting. “I was like, ‘Oh man, how am I going to manage all these kids?’” recalls Brescher, who teaches in Jasper, Ind. Fortunately, parents help at the club’s three-hour fishing events, which take place on two Saturdays in the fall and another two in the spring.

Typically, Brescher gets about 50 students at meetings and events. Of them, five or six are girls. The club is advertised to boys and girls alike, but Brescher notes, “It does attract more boys, and maybe what you’d call the ‘troublemakers.’ It’s their outlet and they thrive out there.”

Fishing equipment is donated. Prior experience isn’t necessary. “We’ve got kids who are avid bass fishermen, flipping a jig around, and others who don’t even know how to tie a hook on,” he says. Everybody is happy when anybody catches anything!

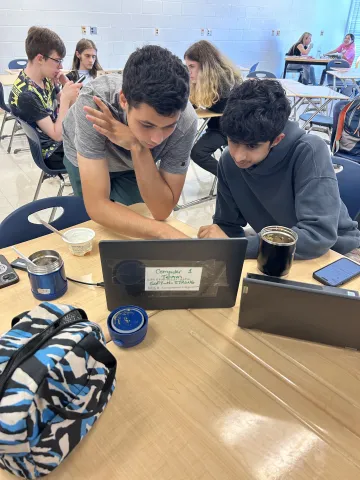

Networking and interfacing

Sozi has about 65 students in the Computer Geeks club at Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School. About 8 in 10 are boys.

Thirty club members (26 boys) participate in CyberPatriot, a national competition that challenges students to secure virtual networks. It’s a precursor to careers in cyber defense, Sozi notes. Another club group works on Python coding, while a third practices web design. All participate in what he calls an “incubator,” where they float ideas and prototype products. Mostly, they meet during lunch.

“I find that male students generally have fewer friends. So, in a club like ours, they can connect through an area of common interest,” Sozi says. “Many of these kids keep these connections for a long time. … They become meaningful people to each other.”

Checkmate!

Illinois paraeducator Kathy Lachowicz is the head coach of the chess team at Alan B. Shepard High School, in Palos Heights—and the only woman coach in her high school’s division. Of her 17 “chessletes,” 14 are boys. They practice twice a week and compete against other local high schools for about seven weeks in the fall.

“I tell the kids, it’s not about the [match] points, it’s about learning new strategies and meeting other kids,” Lachowicz says.

Some of her kids are really high-level thinkers, playing several moves ahead. Others are just winning the snacks she gives them. “I provide cookies, candy, stuff like that. After school, they’re hungry!”