Key Takeaways

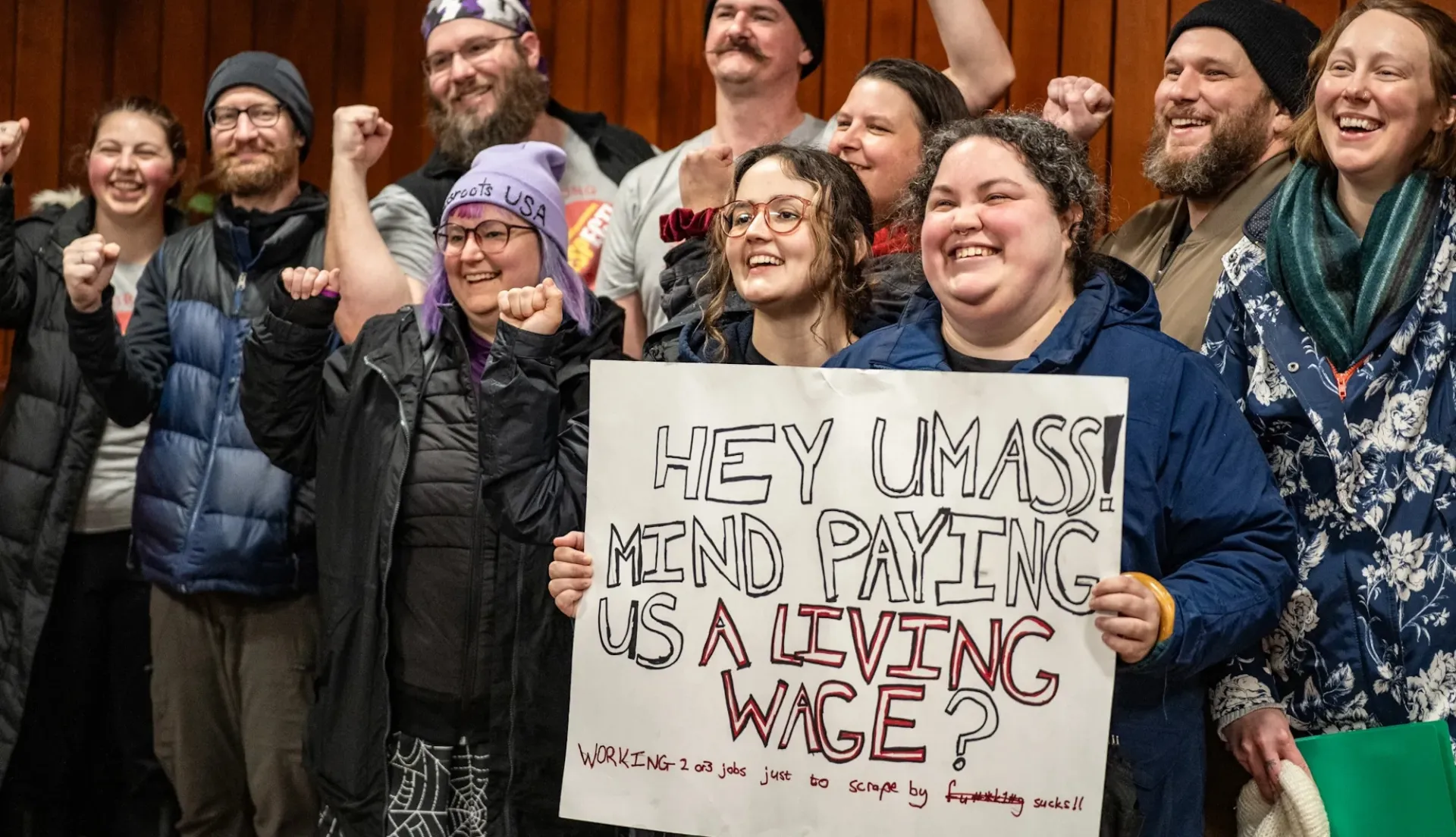

- Low wages are forcing full-time staff members at the University of Massachusetts Boston/Amherst to work multiple jobs and rely on free food from community food pantries.

- These union members do work that is vital to students at UMass Boston and UMass Amherst—but they’re treated like they’re expendable. Management’s attitude seems to be ‘if you don’t like it, then leave.’

- Now, after more than 16 months of fruitless contract negotiations, union members are planning a vote of no-confidence in UMass Amherst Chancellor Javier Reyes.

“I’ve gotten really good with lentils,” says University of Massachusetts Boston research data coordinator Alison White. It’s a culinary skill born of necessity. At her current salary—about $37,200 a year, White can’t afford more typical sources of protein.

She gets free food from a community pantry each Thursday, lives with a roommate that she found on Facebook, has a cell-phone plan that doesn’t really work outside the city, and budgets every single penny. Her monthly allocation for “fun”? It’s $0. On the last day of September, she was $8.42 in the black.

White loves her job, but she is growing more and more demoralized—and poor—as her employer, the University of Massachusetts system, refuses to provide a living wage to all employees.

The latest? After dragging their feet for more than a year at the bargaining table and often arriving unprepared for serious conversations, the UMass administration’s team moved abruptly earlier this month to end negotiations and impose draconian takebacks on the roughly 2,400 members of the Professional Staff Union (PSU) who advise UMass students, manage the universities’ dormitories and award-winning dining services, run its academic departments and research laboratories, provide critical health services, and much, much more.

“The message is: Staff isn’t important,” says A.J. LeBlanc, a University of Massachusetts Amherst education abroad advisor and administrator.

Frustrated and fed up with the retrograde direction of administration’s efforts, PSU members at UMass Amherst are now planning to take a vote of no-confidence in their university’s chancellor in December. When it passes—and there is no doubt that it will—every constituency at Amherst, including faculty, undergrad and graduate students, will have voted no confidence in his leadership.

Who Is Important?

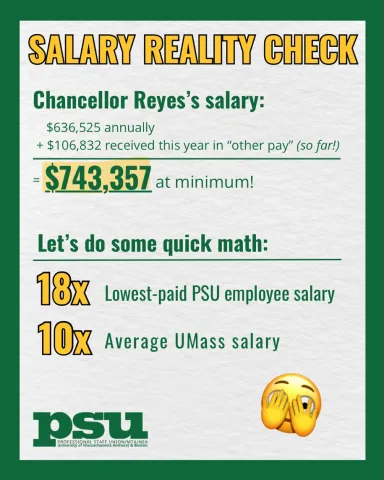

If employee pay is an indicator of employee value, then UMass has made it clear: The new football coach at UMass Amherst is the system’s most valuable employee, with a salary of between $1.3 and $1.4 million per year. In fifth place (after assorted other coaches) is the UMass Amherst chancellor, Javier Reyes, who will get at least $743,357 this year, or about 18 times as much as the lowest paid PSU employee.

By comparison, Chanel Fields makes so little money at UMass Boston that, on top of her full-time job as program coordinator of UMass Boston’s Department of Exercise and Health Science, she works nights and weekends as a security guard.

As program coordinator, Fields supports the department’s directors and faculty; runs her department’s internal and external events, like its recent health professions fair; helps her graduate students put their dissertation together; and connects her undergrads with internships, research opportunities, and graduate programs. (She also does the department’s marketing, including social media.) Like many PSU members, she has a graduate degree. Hers is a master’s degree in public administration, earned at UMass Boston.

Her work is critical to students, but her pay doesn’t show it.

“The message is that staff is expendable,” says LeBlanc. “[But] we’re the ones spending time with kids. We’re the ones seeing them, helping them, getting them resources—everything from, ‘things are going great, do you know about this national scholarship?” to ‘hm, something is not right, we’re going to stop this conversation and I’m going to walk with you to health services,’ which I have actually done.”

The overall graduation rate at UMass Amherst is about 84 percent, or 10 percent above the national average for 4-year public university. PSU members are making that happen, they say.

“We know that if students don’t have a person, they don’t stay. They don’t graduate,” adds LeBlanc. “They need to find a person on campus and, for a lot of them, it’s a PSU member. We’re the ones creating safe spaces for them to talk.”

There Is Money for Raises, Sometimes

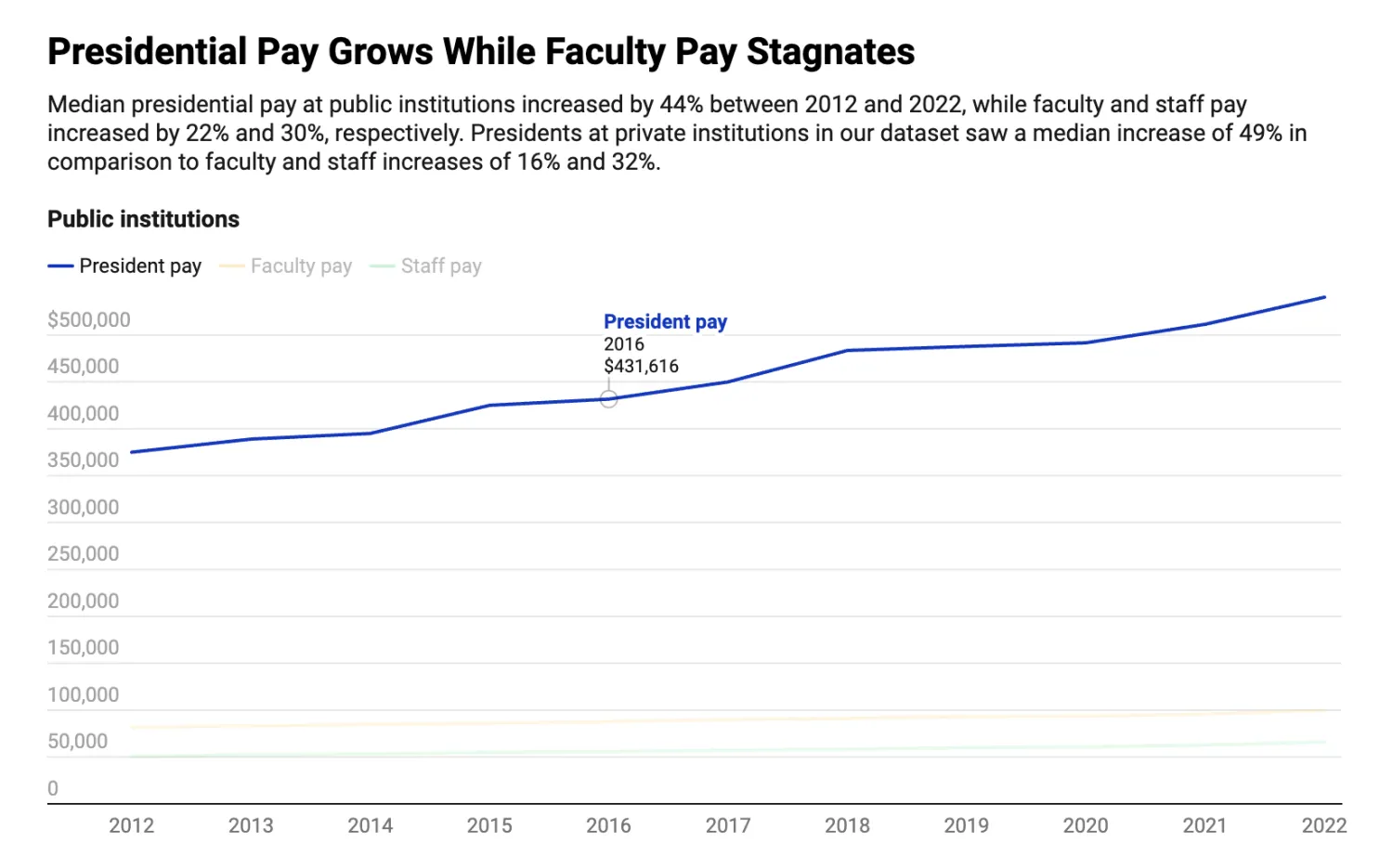

Of course, the UMass system isn’t the only U.S. university opting to spend lavish amounts of money on executive pay while wages for critical workers languish. According to a recent Chronicle of Higher Education analysis, published earlier this month, the median college presidential base salary jumped 53 percent between 2012 and 2022, far outpacing raises for faculty and staff.

At UMass Boston specifically, the Chronicle found that presidential pay grew by 90 percent between 2012-22; at UMass Amherst, it grew by 37 percent.

Meanwhile, the people at the top are also growing more numerous. “People with titles like provost or dean, those structures are growing ever larger,” notes Hannah Bernhard, a UMass Amherst program manager. They’re also getting richer, as executives give themselves the raises that they’re denying poorer employees.

For example, consider this:

- In just one year, from 2024 to 2025, the vice chancellor for human resources at UMass Amherst went from making $145,384.80 to $276,994.54, an increase of 90 percent.

- Between 2020 and 2025, the UMass Amherst chancellor’s chief of staff’s base pay increased from $86,192.33 to $175,869.39, an increase of 104 percent.

- Also, during the same five years, the UMass Amherst athletic director’s pay went from $381,323.24 to $603,222.08, an increase of 58 percent.

“They don’t even try to hide [their pay raises], even if they could, because there’s this warped sense of deservedness,” says Bernhard.

This fall, UMass Amherst’s administrators heralded a new on-campus food pantry, open to hungry students and staff. Bernhard has visited at least four times since the start of the semester. “I think they want us to be grateful that we have this resource without examining how f***-ed up it is that I, a full-time state employee, need to use that resource at all.”

At this point, the only thing that keeps PSU members like LeBlanc in their jobs is how much they love them, despite the low wages and impossible workloads. “We love our jobs. We love our students,” says LeBlanc. My coworkers are amazing—and the way we support each other is incredible.”

“The students are why I stay,” agrees Fields.

What Would a Living Wage Be?

Boston is the fifth most expensive city in the world, just behind Switzerland’s Geneva and Zurich, New York City, and San Francisco, according to Numbeo’s Cost of Living Index. Average rent for a 1-bedroom apartment? It’s $3,455 a month, according to Apartments.com. Buying a home in the city is even more out of reach. The median listing was $869,000 in August, according to Realtor.com—a wild price for a state employee like White.

“I have a partner. I want to get married to them eventually. We both want children. We want to own a house in the city I work in,” says White. Could that ever happen while she works at UMass Boston? The answer is obviously no. Today, she has $340 in her savings account. “If [that amount grows by] $8 a month,” she points out, “I’m never going to be able to afford a house.”

In Boston, a living wage for a single person is $63,939 according to the MIT Living Wage Calculator—about twice as much as White is paid. In Hampshire County, Mass., where Amherst is located, it’s $51,147.

PSU members work and live in both cities, barely. Bernhard lives about 10 miles from Amherst, in Northampton, where average rent for a one-bedroom apartment is about $1,600 a month, not including utilities, she says. Meanwhile, she takes home less than $3,000 a month.

“My salary has never been a living wage, in the six years I’ve worked here,” she says. And, as the cost of living rises, almost every week it seems, “people are only feeling it more and more.”

For years, PSU members have received scant cost-of-living raises that aren’t raises at all. “My paychecks have actually gone down because of increases in healthcare costs and parking fees,” notes Bernhard. “I park half a mile away and I pay hundreds of dollars a year to park at my job, which underpays me! So, it’s not just that the salary is poor, but there are all of these ways to siphon money out of paychecks.”

By declining the union’s reasonable salary proposals, “[university administrators] have basically said, ‘you will not, you should not, make a living wage,’” notes Bernhard.

At the Bargaining Table

PSU’s contract expired in June 2024. They have been at the bargaining table for more than 16 months. At every session, the union’s bargaining team has arrived prepared and ready to go with well-evidenced proposals, including heaps of data, notes LeBlanc, one of many PSU members who has attended bargaining sessions as a silent representative. Dozens of PSU members, including White and Fields, also have shared their personal stories about how a lack of living wage affects them.

Management is rarely as ready, LeBlanc notes. “What has shocked me is the incompetence on the other side, whether it’s real or feigned… sometimes it’s like they haven’t even read their own documents,” she says.

Notes Bernhard: “I could never come to my job as unprepared as executives come to the bargaining table—and yet they make $200K.”

Wages, of course, have been a key issue in contract negotiations. PSU’s proposal would provide a living wage: White, for example, would earn around $60,000, or enough for her to buy eggs again. The university refused that, instead proposing a retrograde of so-called merit raises, taken out of the state’s cost-of-living raises, based on supervisors’ reviews.

“So, if your supervisor arbitrarily decides you don’t deserve to survive, then the institution says you don’t survive. That’s what’s at stake [with merit raises.] It’s not about whether you get to take a vacation this year, it’s about survival,” says Bernhard.

Exhausted, But Empowered

Wages aren’t the only issue. A related issue is workload. As pay stagnates, UMass employees move on to better paying jobs elsewhere. This forces the university system to initiate costly searches for new employees, which often fail because the pay is so low, union members note. Remaining staff members are forced to do the work of two or three people, with no choice about it and no additional pay.

For nine semesters, LeBlanc did two people’s jobs, her own full-time job in UMass Amherst’s Office of Global Affairs plus the full-time job of a student advisor. “I’m working 10-12 hour days, coming in on weekends, asking for help, and it’s like, ‘you’re doing great!’” she says. “It’s all about how can we pay you less and make you do more.”

Stress levels have grown so high in her office that a couple of summers ago, three people got shingles, a viral infection that typically strikes when a person’s immune system is weakened—either by age or by stress. “And one of them was 36!” she says.

Other issues at the bargaining table include protecting LGBTQ+ and immigrant staff, with proposals that would require UMass to fully sponsor and pay for visa applications and to embrace strong policies that defend employees against discrimination.

What it all comes down to, says Bernhard, is getting a contract “that says we matter on this campus.”

While they work toward that, union members are staying strong. “I’m exhausted—and empowered,” says Bernhard.