Key Takeaways

- The EPA defines a heat island as an area, typically urban, where temperatures are significantly warmer than surrounding rural locations.

- For schools in these areas, high temperatures can turn a functional learning environment into a potentially dangerous one.

- In addition to being a health hazard, heat exposure (and the lack of air conditioning) has been linked to lower academic achievement and increased behavioral problems.

In Tempe, Arizona, history teacher Dylan Wince asks his students each year to think about the hottest day they can remember.

Some recall waiting for the public bus in 110-degree heat with no shade. Others talk about losing hundreds of dollars in groceries when a power outage spoiled everything in their refrigerator. A few mention how the heat interacts with medications, making them dizzy or sick.

“At first,” Wince says, “the response is, this is our normal. Then they realize, there’s a name for this [and] a reason.”

That name is the “urban heat island effect.” And in cities across the country, it’s silently shaping the daily realities of our most marginalized students.

Heat Islands Cannot Be Ignored

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines a heat island as an area, typically urban, where temperatures are significantly warmer than surrounding rural locations. This happens because “buildings, roads, and other infrastructure absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat more than natural landscapes.”

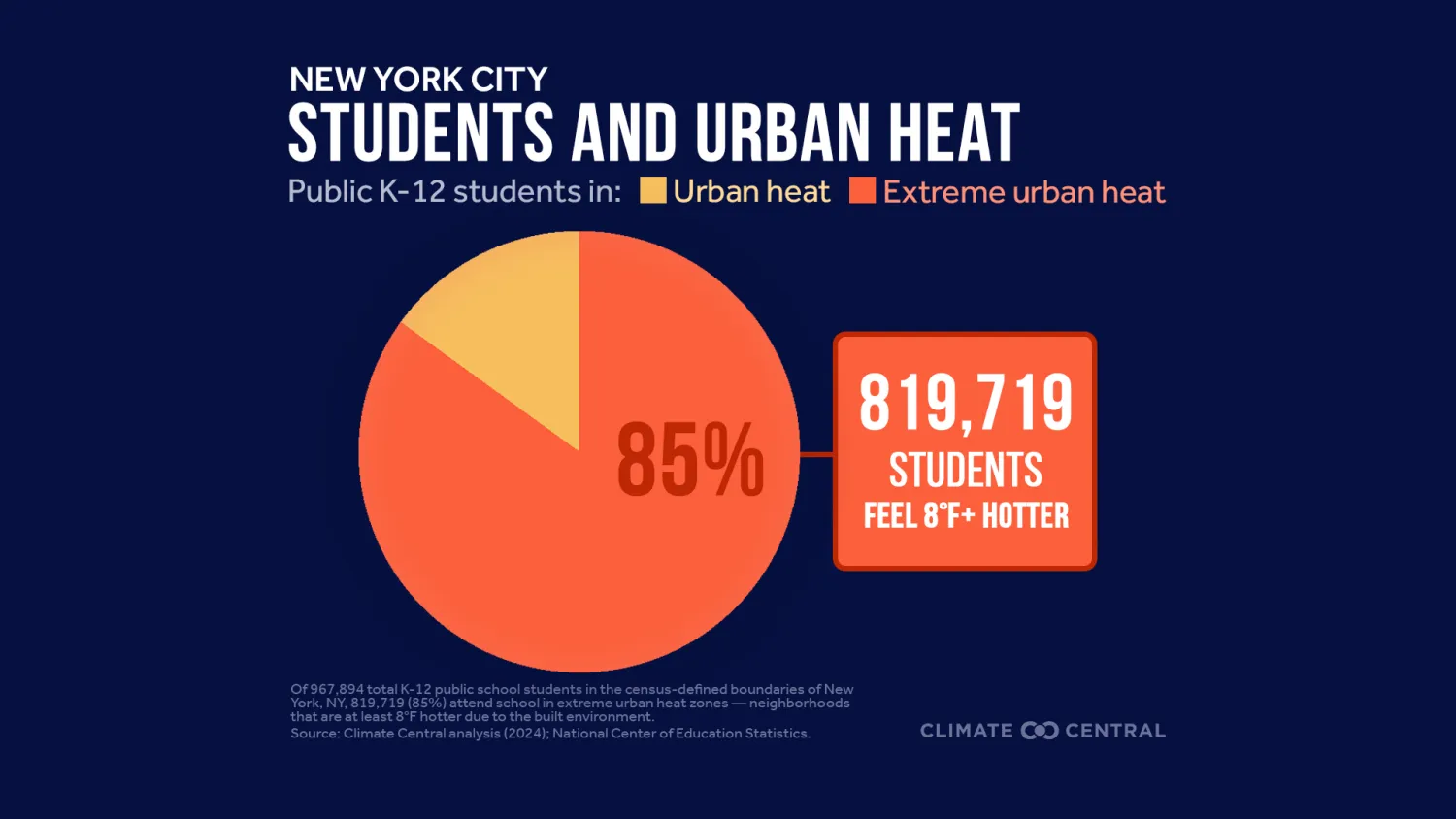

According to EPA data, the heat island effect can make daytime urban temperatures 1-7°F hotter than nearby areas, and nighttime temperatures 2-5°F hotter. The National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS) reports that in some cases, temperatures within the same city can vary by 15-20°F, depending on tree cover, building materials, and shade.

For schools, that temperature gap can be the difference between a functional learning environment and a dangerous one. A 2023 EPA report on Climate Change and Children’s Health and Well-Being in the U.S. found that for each 1°F, increase between May and September, the number of emergency visits at U.S. children’s hospitals could increase by 113 visits per day.

The report also found that Black, Hispanic or Latino, and low-income students have the lowest rates of current air conditioning in schools. Black and Hispanic or Latino students were 1.6% more likely than White students to attend schools with inadequate cooling, and lower-income students were 6.2% more likely than their higher-income peers.

This disparity reflects histories of segregation and redlining, particular in urban areas, which concentrated Black, Hispanic or Latino, and low-income families in underserved neighborhoods where tree cover is sparse, playgrounds are bare asphalt, and shade is a rare luxury—conditions that extend to the schools themselves.

When the Classroom Becomes a Sauna

Eunice Salcedo, senior health and safety specialist at the National Education Association, hears about these conditions daily. “A lot of classrooms don’t have air conditioning,” she explains, “and the ones that do often have broken systems because maintenance is backlogged.” Safety policies sometimes prevent teachers from opening doors for ventilation, and sealed windows mean no airflow at all.

In those classrooms, temperatures rise to the point where teachers are “soaked in sweat” and students are visiting the nurse with heat-related symptoms, Salcedo says. She recalls reports of nosebleeds during class, and an increase in student disciplinary incidents during hot days. These are patterns backed by studies linking heat exposure to declines in academic performance and increased behavioral challenges.

A 2020 study found that students scored increasingly worse on standardized tests each school day where the temperature rose above 80 degrees. And a recent study by Harvard University found that extreme temperatures exacerbate student absenteeism and disciplinary referrals.

Classrooms are not the only locations affected by heat. According to Salcedo, bus drivers report sweltering vehicles, some with A/C systems intentionally disabled or policies that restrict engine use to save costs. For drivers and students, the bus ride to school is another layer of exposure to extreme temperatures.

From Lessons to Heat Action Plans

In Portland, Ore., social studies teacher Tim Swinehart assigns his students mapping projects to help them connect climate science with racial and economic justice. Partnering with local research from Portland State University, his students have seen heat maps showing up to 19°F differences between neighborhoods. The cooler zones tend to be wealthier, whiter, and more tree-lined; the hottest are those shaped by decades of redlining and disinvestment.

“These [neighborhoods] are not far-off places,” Swinehart says. Students recognize them from sports games or family visits. When students see the temperature difference, and learn the history behind it, they ask, “Why haven't I ever learned about this before?”

Students in his classes have channeled that frustration into action, writing articles for the school newspaper, partnering with tree-planting organizations, and even leading peer workshops on the links between housing policy, climate change, and public health.

In Tempe, Wince's students also have a chance to make their voices heard on these issues. His American history classes begin with Indigenous worldviews and the relationships between land, people, and ecosystems. By the time students reach the Gilded Age, they are primed to compare past inequities with modern ones. Environmental injustice is front and center.

Wince does not do this work alone. Working with Evelyn Brumfield, Youth Climate Action Coordinator in the City of Tempe Office of Sustainability and Resilience, Wince’s students study how local heat islands intersect with historic displacement, such as the removal of a Hispanic neighborhood to make way for Arizona State University (ASU).

With support from Rodrigo Palacios, Social Studies Department Lead, and Dr. Carlos Casanova from ASU’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Wince’s students collect personal stories about how extreme heat shapes daily life, then propose solutions directly to city officials.

“If we’re learning about environmental justice and not doing anything with it,” Wince says, “then we’re just wasting time.”

Collective Power for a Lasting Cool

The urban heat island effect is not inevitable. It’s the result of design choices, policy priorities, and neglect, and it can be undone. Victories are possible without waiting for federal mandates.

Educator unions are in a unique position to begin addressing the systems that make classrooms unsafe. In 2022, the Columbus Education Association secured a contract guaranteeing climate control in every learning space by 2026, proving that organized educators and communities can win meaningful, lasting improvements.

Schools can also partner with city agencies and nonprofits to plant shade trees, replace heat- absorbing asphalt with greenery, and invest in cool or green roofs. Such changes lower temperatures, improve air quality, and create spaces where students can focus on learning instead of enduring oppressive heat.

The EPA and the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS) recommend strategies such as increasing urban vegetation, using reflective building materials, and expanding access to air-conditioned public spaces. Schools are in a unique position to lead, both as public facilities that can implement these solutions and as centers where students learn to connect environmental science with real-world action.

“I really appreciated... having students engage with [environmental injustice]” says Swinehart. Wince hopes “to help students develop the tools to go use their different passions in ways that will impact others.”