Stacie Baur knows from experience what a weak salary schedule can do to a career.

Baur was hired, in 2012, by the Clairton City School District, in Pennsylvania, along with 14 other teachers. Only four of them remain in the district today.

“Most left within a few years, and mostly due to the low pay,” says Baur, a fifth-grade math teacher. “They couldn’t wait around to make a salary they could live off of or start a family.”

The salary schedule is considered a sacred principle of unionism: It establishes a rate of pay for each position, called the “career rate,” earned by those who have mastered their craft. It also defines apprenticeship wages, with “steps” that raise a worker’s salary at regular intervals.

Salary schedules are bias-free and prevent discrimination by race, gender, grade level taught, or academic field.

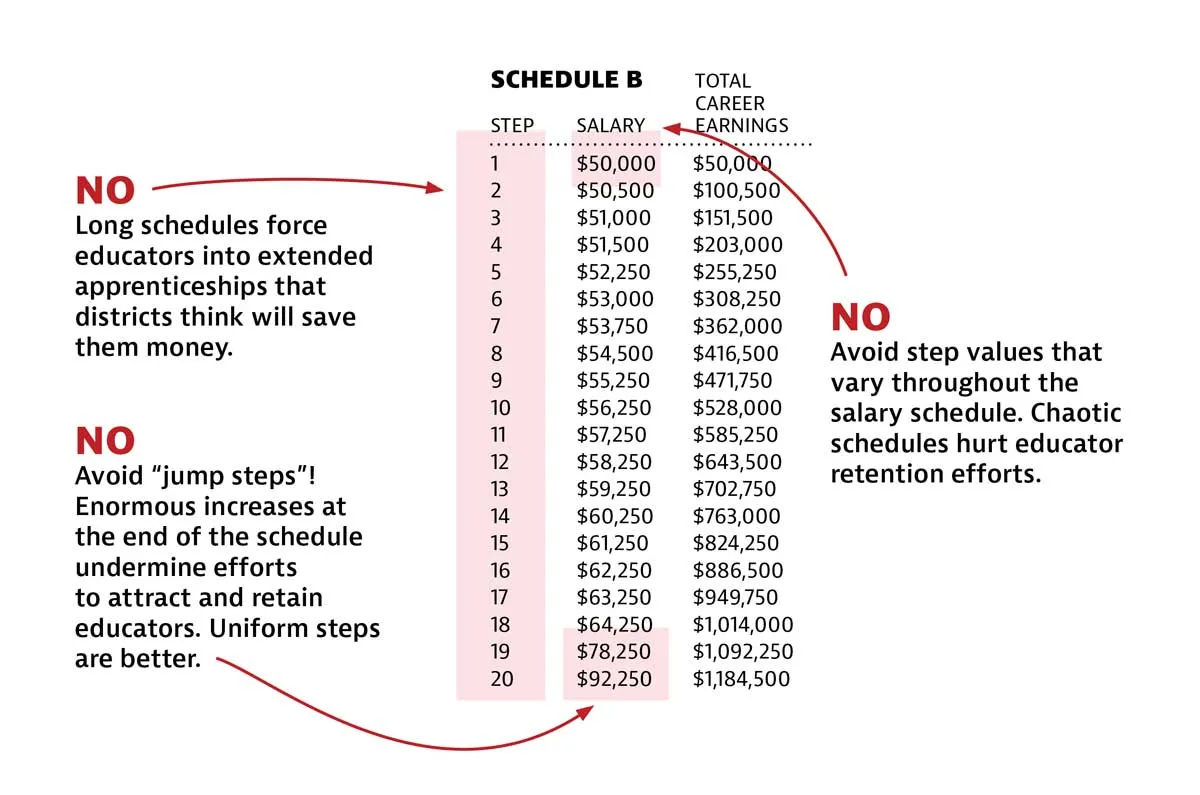

But a weak schedule that takes forever to get to the top—like the one Clairton had—can cost educators hundreds of thousands of dollars over the course of their careers.

As recently as 2019, teachers coming into the Clairton district with a bachelor’s degree were starting at just $38,000. Each step on the salary schedule brought teachers only $500-$750 closer to the career rate. Then in years 16 and 17, their pay would suddenly increase by $20,000 each year (these are called “jump steps” for obvious reasons).

When Baur took on the role of president of the Clairton Education Association, in 2017, she knew the local needed to strengthen their very problematic salary schedule.

They had their chance to make improvements when bargaining commenced in 2020.

“We knew we needed better starting salaries, fewer steps, and more valuable steps,” explains Baur, who brushed up on salary issues at trainings offered by the Pennsylvania State Education Association.

District negotiators acknowledged that low salaries and the long wait for an enormous raise were pushing teachers out the door. In the end, they agreed to the union’s demands, resulting in tremendous improvements over the five-year contract.

Once they reduced the enormous jump steps at the top, they were able to increase the value of all the steps on the salary schedule; raise the starting salary by $10,000; and reduce the total number of steps to just 11. At press time, the local was back at the bargaining table, working on even more improvements.

Baur’s best advice for negotiating a better salary schedule: “First, educate yourself, whether you’re a local leader or a member. This is our salary schedule, our money, and we can’t educate the district until we understand it all ourselves,” Baur says. “Lean on your Uniserv director [a member of your state affilate staff] for help—we couldn’t have accomplished this without ours!”

What does a good salary schedule look like?

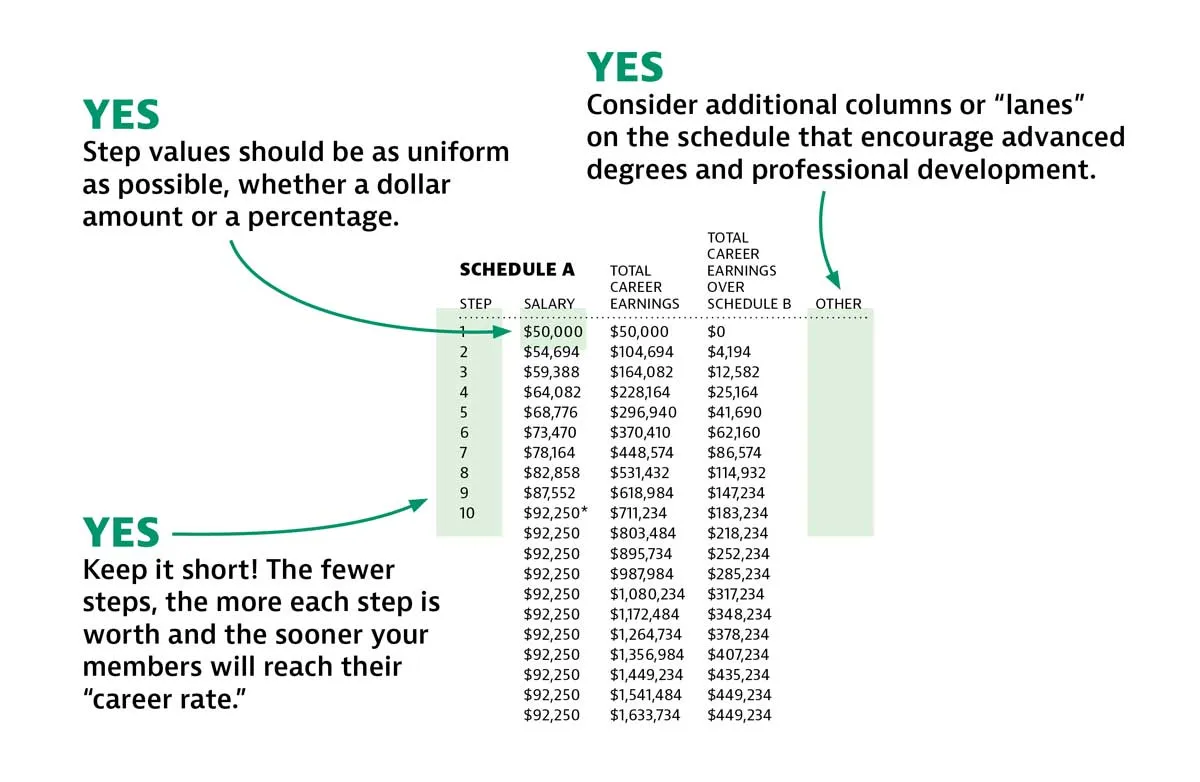

Strong and short—that’s the best description of an ideal salary schedule. In fact, NEA recommends no more than 10 steps to reach the maximum salary.

Why is that important? A “strong, short” salary schedule moves employees efficiently from entry level to the maximum rate of compensation over a reasonable number of steps.

Look at it this way: Districts want to incentivize educators to stay and grow and eventually become a master of their craft. But do they really think that takes 15, 20, or 25 years? Research shows, it takes around 7–10 years in the teaching field. A good salary schedule reflects that.

When it comes to salary schedules... DO THIS, NOT THAT!

For ease of comparison, the salary schedule examples below do not include cost of living increases--but by all means, your union should fight for those!

Bonus Tips!

Learn more about educator pay in your state.