State Funding Update: The Fiscal and Political Crossroads Facing Public Higher Education

Key Takeaways

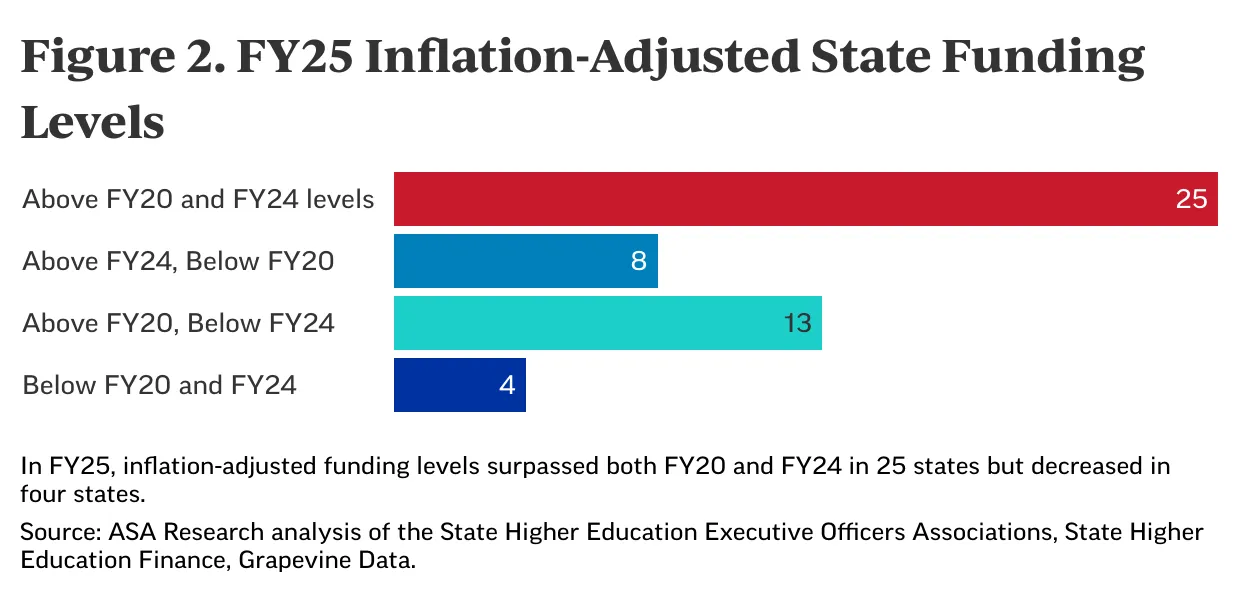

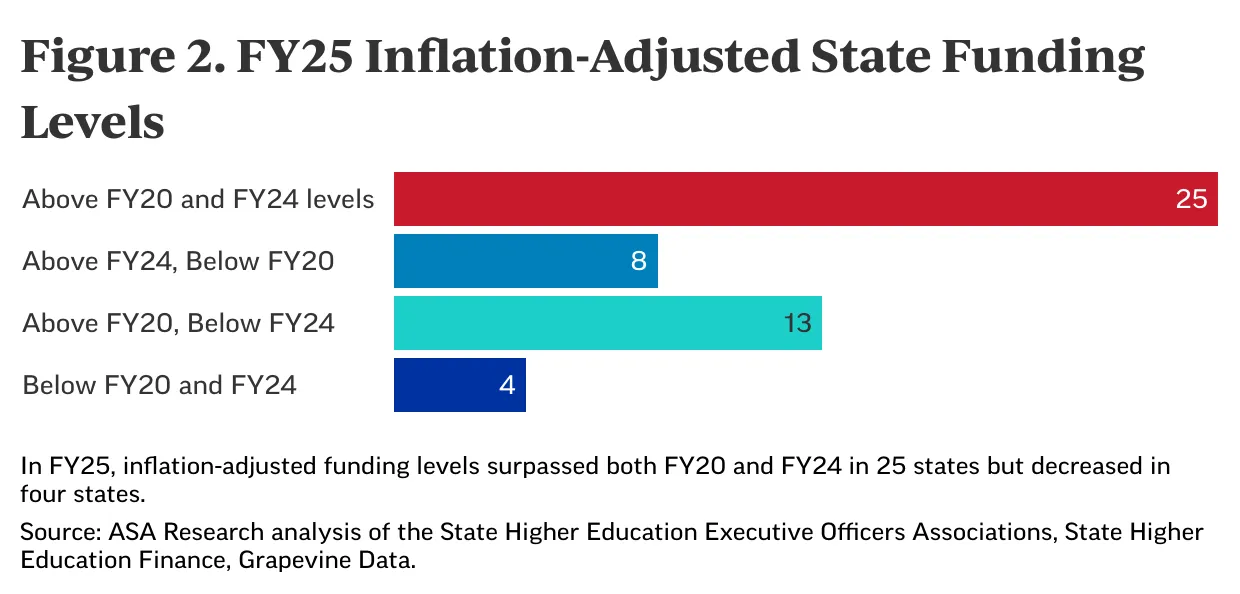

- State appropriations for higher education were $129.0 billion in FY25, a 4 percent one-year increase (which is only a 2 percent increase when adjusted for inflation). However, in inflation-adjusted dollars, 17 states experienced declines from FY24. Encouragingly, 25 states reported funding levels in FY25 that surpassed both FY20 and FY24, signaling more robust and sustained reinvestment in public higher education.

- The current administration’s actions, including tariffs, layoffs, indirect cost caps, and cuts to research funding, are leaving many states bracing for funding uncertainty in higher education in FY26.

- On a positive note, 38 states have surpassed recent pre-pandemic levels in total inflation-adjusted state appropriations; however, inconsistent enrollment data makes it difficult to determine whether per-student funding has truly recovered.

Introduction

State funding for higher education in the United States has long followed the broader economic cycle—expanding during periods of growth and contracting during downturns. State fiscal health and political priorities have further amplified this financial volatility, resulting in uneven and unpredictable funding landscapes across the country. These fluctuations pose persistent challenges to public colleges and universities, which depend heavily on state appropriations to support faculty and staff salaries, provide student aid, and maintain essential services.

States often see higher education as having an alternate funding mechanism—tuition—unlike most state budget items. So, when public investment falls, students and their families frequently absorb the financial burden in the form of higher tuition and fees. This perceived substitute makes higher education particularly vulnerable to cuts. However, along with funding cuts, states also often cap increases in tuition, putting even greater pressure on institution finances.

State funding became especially volatile during the Great Recession in 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic, both of which caused states to make significant cuts in public investment. Some states were unable to fully recover. As the country emerges from the pandemic, we are experiencing a new period of fiscal and political uncertainty marked by inflation, shifting budget priorities, and Trump administration policies. The current administration has intensified its attacks on higher education, including efforts to dismantle diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) initiatives; restrict free speech; freeze or halt publicly funded research; significantly raise the tax on endowments; and limit indirect cost reimbursement for research activities. At a time when strong state appropriations could make a critical difference, many colleges and universities instead are facing tightened budgets and mounting political scrutiny, with continuous threats to education equity, academic freedom, and institutional stability.

This report examines how state funding for higher education has fluctuated across economic cycles, drawing on national trends, historical state-level data, and contextualized examples from individual states. By integrating findings from NEA’s prior reports in other research areas, we assessed the structural vulnerabilities that make public colleges and universities particularly susceptible to fiscal downturns and shifting political priorities. In addition, we highlight in this brief the mounting financial pressures facing these institutions due to the proposed caps on indirect costs for funded research—an often-overlooked but critical revenue stream that supports the infrastructure necessary for higher education institutions to conduct research.

Historical Trends

The Great Recession and Recovery. Historical information summarized from the National Education Association, State Higher Education Funding Highlights Update (February 2025), https://www.nea.org/sites/default/files/2025-02/state-higher-ed-funding-highlights-update.pdf. Go to reference State funding for higher education was at a historic high in the 2008 fiscal year (FY08), just before the Great Recession. During the recession and into the recovery years, funding levels dipped significantly but then began to recover in the years just before the pandemic, and by FY20, higher education appropriations were at higher levels than FY08 funding in 40 states. However, adjusting for inflation and measured on a per-student basis, only 18 states’ funding recovered to pre-recessionary levels; 32 states had not completely recovered, although many were on the upswing.

The COVID-19 Pandemic. The economic effects of the pandemic began in mid-FY20, putting states and institutions into an economic tailspin. As a result, most states slashed their FY21 higher education budgets. Inflation-adjusted higher education appropriations declined in 37 states between FY20 and FY21, and among the other 13 states, increases were small. At the same time, enrollment declined, resulting in funding-per-student declines in many states.

Adding insult to injury, the high pandemic-era inflation resulted in further financial pressure. Although only five states experienced decreases in actual total higher education state funding between FY21 and FY22, all but two states (Colorado and Pennsylvania) experienced drops in inflation-adjusted funding per student between FY21 and FY22.

FY23. FY23 marked the beginning of a recovery phase, and many states increased higher education funding levels, with some increasing funding by double digits compared to FY22. In fact, all but one state (Arkansas) met or exceeded FY22 funding levels in FY23. Increases were so strong that even when taking inflation into account and measuring on a per-student basis, funding decreased in only five states between FY22 and FY23 and increased quite significantly in others.

FY24. State funding for higher education totaled $123.6 billion in FY24, a 9 percent increase over FY23, and the third year that higher education funding exceeded $100 billion. This differs from prior reports as data are adjusted when more accurate data become available. Go to reference Only four states spent less on higher education in FY24 than in FY23. But, when taking inflation into account, FY24 higher education funding was lower than FY23 levels in nine states. At the time of this report, enrollment data and resulting funding on a per-student basis were not yet available.

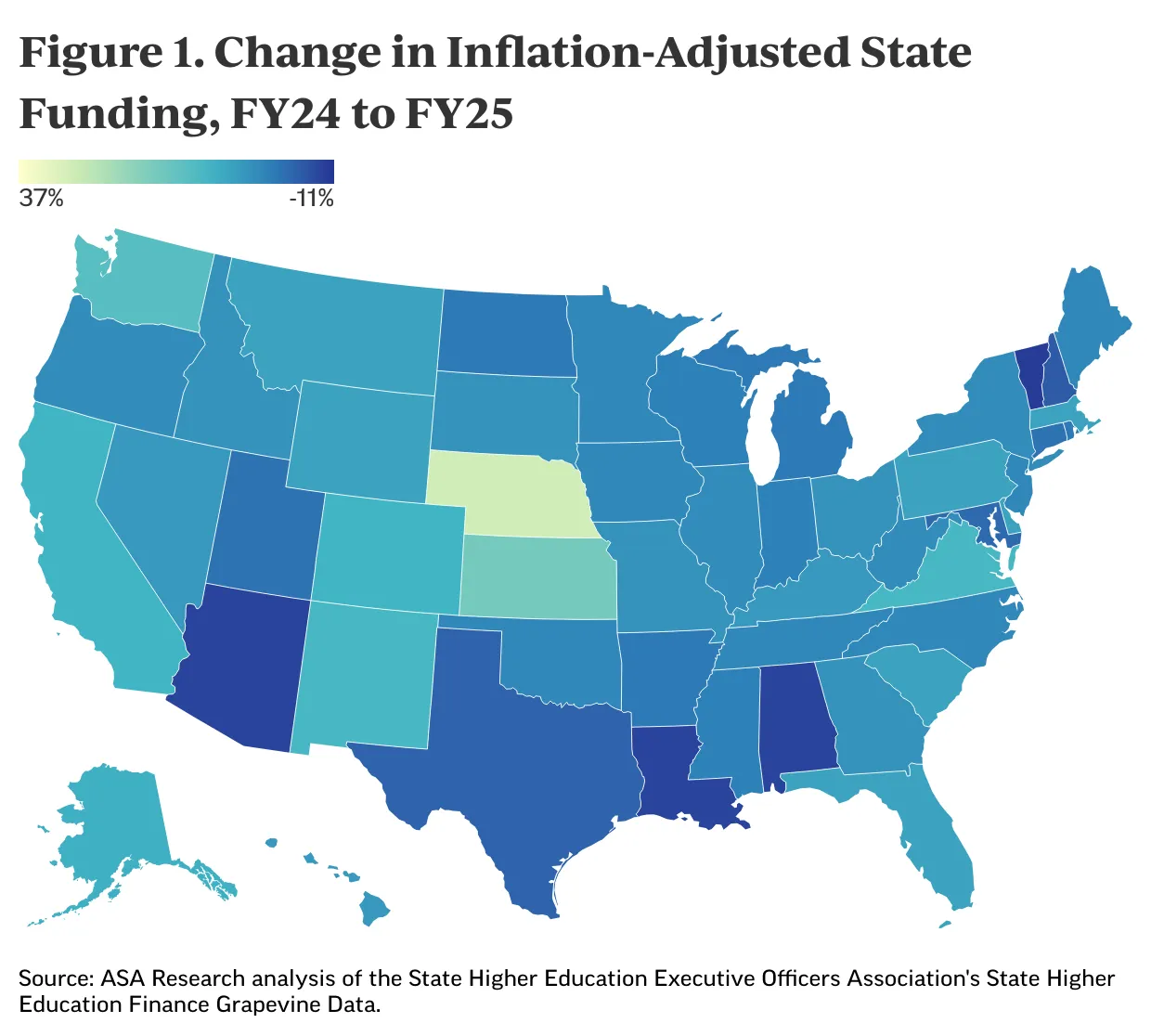

FY25. The state funding analysis is based on data made available by the State Higher Education Executive Officers Associations, State Higher Education Finance, Grapevine Data (https://shef.sheeo.org/grapevine/). Go to reference State appropriations for higher education were $129.0 billion in FY25, a 4 percent one-year increase (which is only a 2 percent increase when adjusted for inflation). However, in inflation-adjusted dollars, 17 states experienced declines from FY24. Vermont, Arizona, and Alabama experienced the largest declines, 9 to 10 percent. Interestingly, at the same time, National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) estimated that enrollment in Arizona’s and Alabama’s public institutions increased by 6 and 3 percent, respectively, thus further eroding funding levels on a per-student basis; Vermont’s enrollment shifts over these years were not reported. Kansas, Nebraska, and Washington State experienced double-digit increases in inflation-adjusted funding (15, 29, and 11 percent, respectively) while estimated enrollment in each of these states declined (2, 4, and 3 percent, respectively), resulting in increases in funding levels per student (See Figure 1. below). National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (January 23, 2025). Current Term Enrollment Estimates: Fall 2024 Expanded Edition. https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/researchcenter/viz/CTEEFall2024dashboard/CTEEFall2024. Go to reference

- 1 Historical information summarized from the National Education Association, State Higher Education Funding Highlights Update (February 2025), https://www.nea.org/sites/default/files/2025-02/state-higher-ed-funding-highlights-update.pdf.

- 2 This differs from prior reports as data are adjusted when more accurate data become available.

- 3 The state funding analysis is based on data made available by the State Higher Education Executive Officers Associations, State Higher Education Finance, Grapevine Data (https://shef.sheeo.org/grapevine/).

- 4 National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (January 23, 2025). Current Term Enrollment Estimates: Fall 2024 Expanded Edition. https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/researchcenter/viz/CTEEFall2024dashboard/CTEEFall2024.

FY25 Funding Compared to Pre-Pandemic Funding

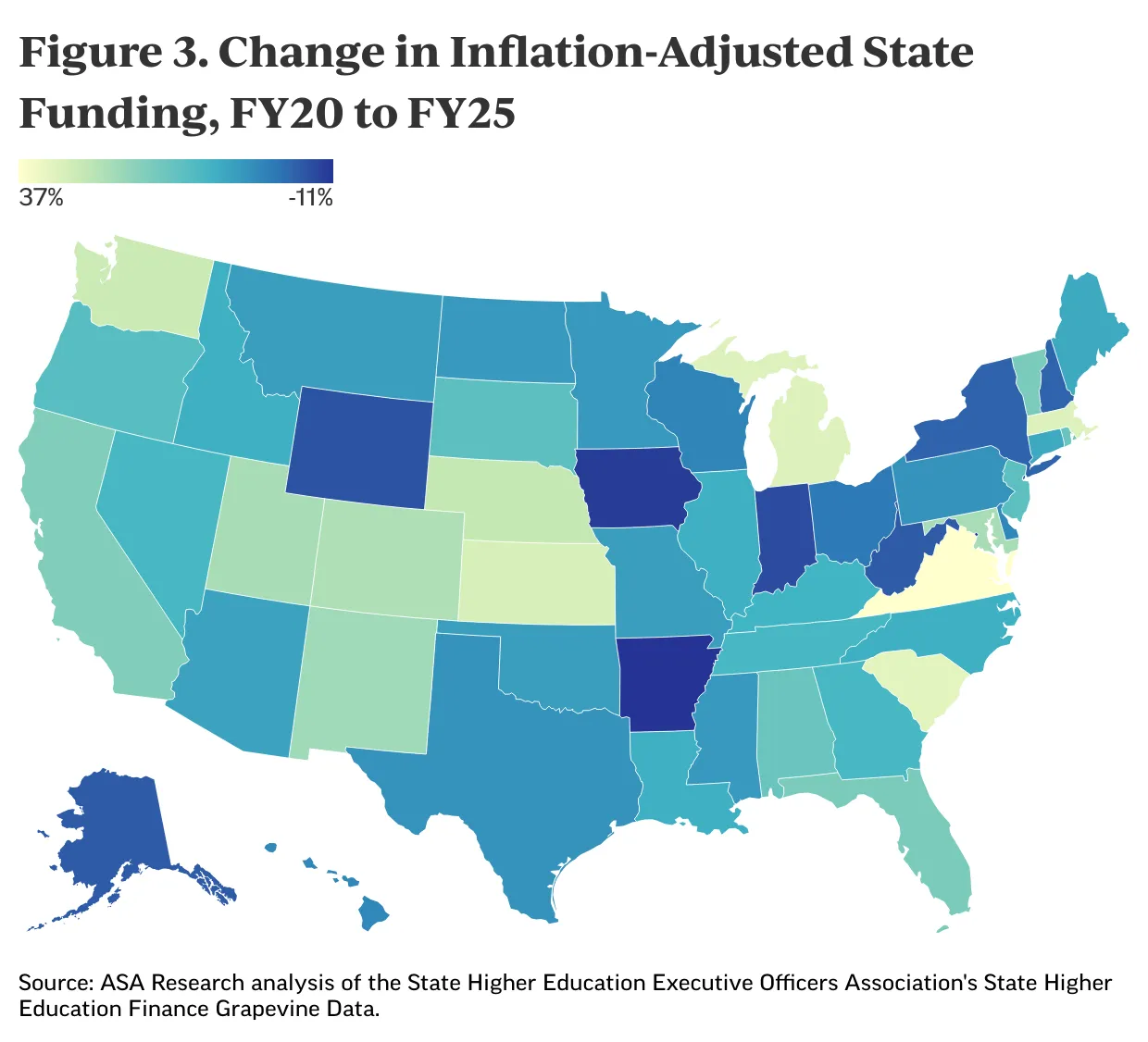

Inflation-adjusted state funding for higher education shows varying degrees of recovery from pandemic-era disinvestment across the country. In total dollars, 12 states experienced inflation-adjusted funding declines between FY20 and FY25. Arkansas took the hardest hit, 11 percent, followed by Iowa and Indiana, 10 and 8 percent, respectively. In four states—Arkansas, Indiana, New Hampshire, and Wisconsin—funding declined between both FY20 and FY25, and FY24 and FY25, indicating that support not only remains below pre-pandemic levels but also showed no sign of recovery in the most recent year (See Figure 2).

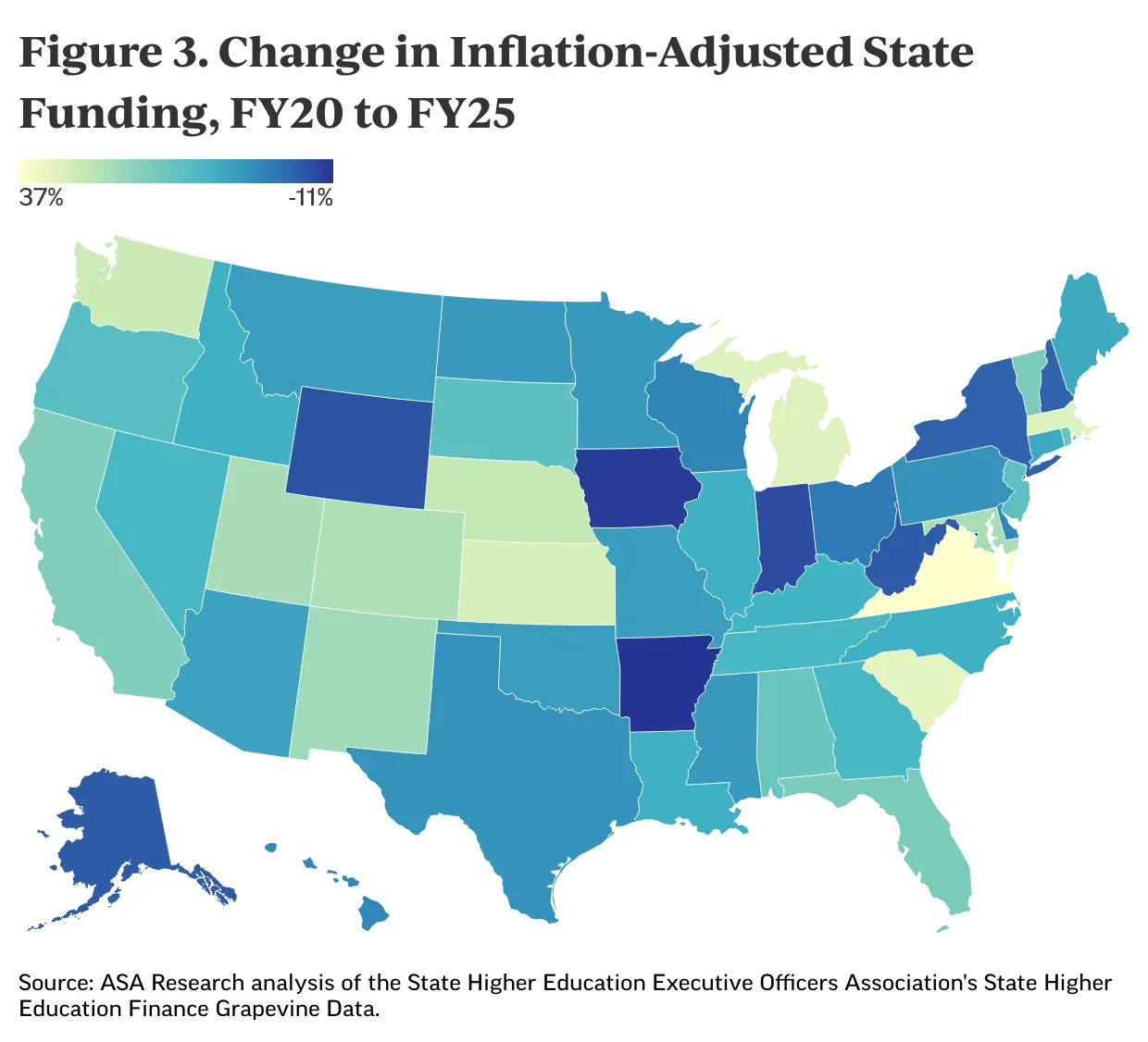

In contrast, 13 states (Alabama, Arizona, Connecticut, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Texas, Utah, and Vermont) experienced one-year declines since FY24 but maintained higher funding levels in FY25 than before the pandemic. Another eight states (Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Iowa, New York, Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin) saw increases in higher education funding between FY24 and FY25, though FY25 levels lagged behind FY20, suggesting a delayed effort to recover from pandemic-era cuts. Encouragingly, 25 states reported funding levels in FY25 that surpassed both FY20 and FY24, signaling more robust and sustained reinvestment in public higher education. (See Figure 3 for state-by-state changes in funding between FY20 and FY25.)

FY26 State Budgets

Most state budgets operate on a fiscal year that runs from July 1 to June 30. Governors typically propose their budgets between December and February, with legislatures deliberating them during sessions that begin early in the calendar year. States typically approve and enact final budgets in the spring or early summer.

The current administration’s actions have made this year’s budget process especially challenging. Before Trump’s inauguration, governors had to anticipate the priorities of the incoming administration as they drafted their budget proposals. Then, state legislatures debated these budgets in the early months of his presidency amid significant political turmoil and uncertainty. Factors like tariffs, layoffs, and broader economic instability are contributing to expected slowdowns in state revenue growth. Adding to the pressure, the current administration has frozen billions of dollars that states rely on to support after-school programs, public health agencies, disaster relief, and other essential services. As a result, many states are bracing for reduced federal funding for critical areas, such as education, health care, and transportation. Some states are also setting aside reserves in anticipation of a potential economic downturn, possible cuts to federally funded programs—such as Medicaid, which is jointly administered by the federal government and the states—and the legal and financial uncertainties stemming from these federal actions. Kilgore, E. (May 8, 2025). Trump’s Agenda Will Hammer State and Local Governments. New York Magazine. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/trumps-agenda-will-hammer-state-and-local-governments.html. Go to reference While states are drafting budgets based on current information, many are closely monitoring federal developments and anticipating the need for mid-year special sessions to reassess and revise their financial plans. Quinton, S. (April 17, 2025). What Federal Chaos Means for State Budgets. Pluribus News. https://pluribusnews.com/news-and-events/what-federal-chaos-means-for-state-budgets/. Go to reference At the time of this report, 15 states (Delaware, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, and Wyoming) have passed their FY26 budgets.

The Landscape of Higher Education Funding

State budgets for FY26 will be a complex landscape for higher education funding across the United States. Influenced by economic conditions, political priorities, and structural considerations, some states are increasing investments, while others are implementing cuts or structural changes. The following developments highlight some of the varied approaches states are taking toward higher education funding in FY26.

States Increasing or Stabilizing Higher Education Funding

Arkansas

The proposed FY26 budget allocates $777 million in state aid to institutions of higher education. This represents a modest increase of approximately $6 million compared to the FY25 allocation of $771 million. The higher education funding continues to be distributed based on Arkansas's productivity-based funding model, which reallocates resources among institutions based on performance metrics. This approach aims to incentivize improvements in areas such as graduation rates and student success without requiring substantial new general revenue funds. Sparkman, W. (November 22, 2024). Education, Maternal Health Top Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders' Budget Plan. Axios. https://www.axios.com/local/nw-arkansas/2024/11/22/sarah-huckabee-sanders-budget-education-health. Go to reference

Illinois

The governor’s proposed budget includes a 3 percent increase in funding for colleges and universities, totaling $46 million. This comprises a $37 million boost for public universities and $9 million for community colleges. Bowman, M. (February 21, 2025). Partnership for College Completion Responds to Governor Pritzker’s FY26 Budget Address. Partnership for College Completion. https://partnershipfcc.org/partnership-for-college-completion-responds-to-governor-pritzkers-fy26-budget-address/. Go to reference

Maryland

The proposed FY26 budget includes a $47.2 million, or 1.5 percent, increase in operational support for higher education. However, this includes prior-year salary adjustments, making the actual increase more modest, and depending on the final funding level, it could be negative. Department of Legislative Services. (January 2025). Operating Budget Analysis: Higher Education – Fiscal 2026 Budget Overview. Maryland General Assembly. https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/pubs/budgetfiscal/2026fy-budget-docs-operating-HIGHED-Higher-Education-Overview.pdf. Go to reference

Wisconsin

The proposed FY26 higher education budget represents a significant investment in the state's public colleges and universities. In recent years, the University of Wisconsin System faced budget deficits and declining enrollments, leading to the closure of several branch campuses. The proposed budget includes more than $856 million aimed at preventing layoffs, campus closures, and program cuts. The proposed budget also includes a 5 percent pay increase for university employees, increases to funding for Wisconsin Grants (which provide financial assistance to students), funding for technical college students who are enrolled less than half-time, and funds to expand the Nurse Educators Program. Wisconsin Department of Administration. (February 2025). 2025–27 Budget in Brief. https://doa.wi.gov/budget/SBO/2025-27%20Budget%20in%20Brief%20UEK.pdf. Go to reference

States Implementing Cuts or Facing Challenges

Colorado

The FY26 enacted budget allocates less than half of the funding that institutions requested, and the budget caps public college and university tuition increases at 3.5 percent. Ventrelli, M. (April 28, 2025). Colorado Lawmakers Warn Financial Woes Are Just Beginning as Gov. Jared Polis Signs $44B Budget. Colorado Politics. https://www.coloradopolitics.com/governor/colorado-budget-signing/article_76cb6ca7-535d-4261-bd04-7d9305c4e5f7.html. Go to reference

New Hampshire

Historically, most state funding for universities has been used to keep tuition affordable for students. However, the House proposed a 30 percent reduction in funding in FY26. University leaders argue that raising tuition is not an option because they will lose students. They are concerned that operating at this deficit will require sacrifices to services and a massive restructuring. Matherly, C. (April 30, 2025). Facing 30% Budget Cut, State University Leaders Say Raising Tuition Is Not an Option. New Hampshire Public Radio. https://www.nhpr.org/politics/2025-04-30/facing-30-percent-budget-cut-university-new-hampshire-leaders-say-raising-tuition-not-an-option?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Go to reference Note, New Hampshire was shown in past reports to have ongoing struggles with higher education funding.

New Jersey

The proposed FY26 budget reflects a $200 million overall reduction in higher education funding, with community colleges experiencing a notable $20 million decrease in operating aid. Additionally, the 18 percent cut to the Community College Operating Grant (CCOG) program in FY26 is a significant shift in student financial assistance. These proposed reductions have raised concern that decreased funding could adversely affect student access, retention, and the overall quality of higher education, and it would eliminate critical assistance to approximately 6,000 lower- and middle-income students. Myles, C., & Chambers, A. (May 2025). Fiscal Year 2025–2026 Higher Educational Services Budget Analysis. New Jersey Office of Legislative Services. https://pub.njleg.state.nj.us/publications/budget/governors-budget/2026/HES_analysis_2026.pdf. Go to reference New Jersey Council of County Colleges. (March 18, 2025). Fact Sheet: Critical Need for State Investment in Community Colleges in the FY 2026 State Budget. https://www.njcommunitycolleges.org/news/fact-sheet-critical-need-for-state-investment-in-community-colleges-in-the-fy-2026-state-budget/. Go to reference

Structural and Governance Changes

Indiana

The proposed budget contains non-monetary changes, including a provision that grants the governor complete authority over the Indiana University Board of Trustees, and allows the governor to eliminate previously elected positions. The proposal also includes a provision that will require faculty to post their syllabi online and undergo productivity reviews. Quinn, R. (April 30, 2025). Indiana Budget Bill Contains Sweeping Higher Ed Changes. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/faculty-issues/academic-freedom/2025/04/30/indiana-budget-bill-contains-sweeping-higher-ed. Go to reference

- 5 Kilgore, E. (May 8, 2025). Trump’s Agenda Will Hammer State and Local Governments. New York Magazine. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/trumps-agenda-will-hammer-state-and-local-governments.html.

- 6 Quinton, S. (April 17, 2025). What Federal Chaos Means for State Budgets. Pluribus News. https://pluribusnews.com/news-and-events/what-federal-chaos-means-for-state-budgets/.

- 7 Sparkman, W. (November 22, 2024). Education, Maternal Health Top Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders' Budget Plan. Axios. https://www.axios.com/local/nw-arkansas/2024/11/22/sarah-huckabee-sanders-budget-education-health.

- 8 Bowman, M. (February 21, 2025). Partnership for College Completion Responds to Governor Pritzker’s FY26 Budget Address. Partnership for College Completion. https://partnershipfcc.org/partnership-for-college-completion-responds-to-governor-pritzkers-fy26-budget-address/.

- 9 Department of Legislative Services. (January 2025). Operating Budget Analysis: Higher Education – Fiscal 2026 Budget Overview. Maryland General Assembly. https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/pubs/budgetfiscal/2026fy-budget-docs-operating-HIGHED-Higher-Education-Overview.pdf.

- 10 Wisconsin Department of Administration. (February 2025). 2025–27 Budget in Brief. https://doa.wi.gov/budget/SBO/2025-27%20Budget%20in%20Brief%20UEK.pdf.

- 11 Ventrelli, M. (April 28, 2025). Colorado Lawmakers Warn Financial Woes Are Just Beginning as Gov. Jared Polis Signs $44B Budget. Colorado Politics. https://www.coloradopolitics.com/governor/colorado-budget-signing/article_76cb6ca7-535d-4261-bd04-7d9305c4e5f7.html.

- 12 Matherly, C. (April 30, 2025). Facing 30% Budget Cut, State University Leaders Say Raising Tuition Is Not an Option. New Hampshire Public Radio. https://www.nhpr.org/politics/2025-04-30/facing-30-percent-budget-cut-university-new-hampshire-leaders-say-raising-tuition-not-an-option?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- 13 Myles, C., & Chambers, A. (May 2025). Fiscal Year 2025–2026 Higher Educational Services Budget Analysis. New Jersey Office of Legislative Services. https://pub.njleg.state.nj.us/publications/budget/governors-budget/2026/HES_analysis_2026.pdf.

- 14 New Jersey Council of County Colleges. (March 18, 2025). Fact Sheet: Critical Need for State Investment in Community Colleges in the FY 2026 State Budget. https://www.njcommunitycolleges.org/news/fact-sheet-critical-need-for-state-investment-in-community-colleges-in-the-fy-2026-state-budget/.

- 15 Quinn, R. (April 30, 2025). Indiana Budget Bill Contains Sweeping Higher Ed Changes. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/faculty-issues/academic-freedom/2025/04/30/indiana-budget-bill-contains-sweeping-higher-ed.

Indirect Cost Rate Caps: Additional Financial Pressures on Institutions

Higher education institutions apply indirect cost rates, a percentage, to federally sponsored research—for example, projects funded through grants or contracts—to reimburse that institution for the overhead costs. Indirect costs are not easily attributable to a specific project and generally are divided into two categories: facilities, which includes building operation and maintenance, utilities, library services, etc.; and administrative, which includes human resources, project management, compliance, etc. At some institutions, indirect cost rates can exceed 60 percent.

Federal agencies—such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Energy (DOE), and National Science Foundation (NSF)—have announced plans to cap indirect cost rates at 15 percent for grants awarded to higher education institutions. National Institutes of Health. (February 7, 2025). Supplemental Guidance to the 2024 NIH Grants Policy Statement: Indirect Cost Rates (Notice No. NOT-OD-25-068). https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-25-068.html. Go to reference Trager, R. (April 17, 2025). US Energy Department Cap on Indirect Research Costs Temporarily Halted After Universities File Lawsuit. ChemistryWorld. Royal Society of Chemistry. https://www.chemistryworld.com/news/us-energy-department-cap-on-indirect-research-costs-temporarily-halted-after-universities-file-lawsuit/4021358.article?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Go to reference National Science Foundation. (May 2, 2025). Policy Notice: Implementation of Standard 15% Indirect Cost Rate. https://www.nsf.gov/policies/document/indirect-cost-rate. Go to reference This proposed cap threatens to reduce research capacity, delay scientific progress, and weaken the United States’ leadership position in global innovation. A coalition of universities and higher education associations filed lawsuits against both the NIH and DOE policies, Spitalniak, L. (May 7, 2025). National Science Foundation Faces Lawsuit Over 15% Indirect Research Cap. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/national-science-foundation-faces-lawsuit-over-15-indirect-research-cap/747385/. Go to reference with injunctions currently blocking the NIH cap and temporarily halting the DOE cap. Unglesbee, B. (April 7, 2025). Judge Permanently Blocks NIH’s Plan to Cap Funding, Setting Up Appeals Battle. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/judge-permanently-blocks-nihs-plan-to-cap-funding-setting-up-appeals-batt/744647/. Go to reference Zhang, C. (April 16, 2025). Judge Blocks DOE Move to Cut Indirect Cost Rate. AIP FYI. https://ww2.aip.org/fyi/judge-blocks-doe-move-to-cut-indirect-cost-rate. Go to reference Similarly, a U.S. District Court struck down the NSF’s cap on indirect costs. Higher Ed Dive. (August 18, 2025). Tracking the Trump administration’s moves to cap indirect research funding. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/tracking-the-trump-administrations-moves-to-cap-indirect-research-funding/751123/. Go to reference Meanwhile, institutions are proactively mitigating the potential impact of these caps by implementing hiring freezes, eliminating vacant positions, and offering voluntary buyouts. Unglesbee, B. (March 20, 2025). University of California Freezes Hiring as It Braces for Funding Cuts. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/university-of-california-hiring-freeze-trump-cuts-nih/743121/. Go to reference Svrluga. S. (March 3, 2025). Hiring Freezes, Fewer Grad Students: Funding Uncertainty Hits Colleges. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2025/03/03/universities-budgets-nih-indirect-cost-cuts/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Go to reference Colleges and universities may also consider diversifying funding sources, revising grant budgets to reclassify eligible indirect costs as direct costs, and leveraging internal resources, such as endowments and fundraising campaigns, to sustain research infrastructure. Stabach, J. (February 15, 2025). Understanding NIH’s 15% Indirect Cost Cap: What Universities Need to Know. ARES Scientific. https://aresscientific.com/blog/nih-15-indirect-cost-cap-key-insights/. Go to reference

In addition to capping indirect costs, the Trump administration has canceled thousands of federal research grants, wiping out billions of dollars in health, education, environmental, and STEM funding for higher education institutions. For instance, the NSF canceled more than 1,500 grants and contracts, 90 percent of which related to diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) studies. Schwabish, J., & Axelrod, J. (July 9, 2025). NSF has canceled more than 1,500 grants. Nearly 90 percent were related to DEI. The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/nsf-has-canceled-more-1500-grants-nearly-90-percent-were-related-dei. Go to reference Recently, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Trump administration’s cancellation of approximately $783 million in research grants from the NIH. These cancellations extend Trump’s attacks on DEIA. Public schools were awarded approximately 800 of the more than 1,700 NIH grants canceled. Quinn, M. (August 22, 2025). Supreme Court clears way for Trump admin. To cancel NIH grants related to diversity, gender identity. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/supreme-court-clears-trump-admin-cancel-nih-diversity-gender-identity-related-grants/. Go to reference

- 16 National Institutes of Health. (February 7, 2025). Supplemental Guidance to the 2024 NIH Grants Policy Statement: Indirect Cost Rates (Notice No. NOT-OD-25-068). https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-25-068.html.

- 17 Trager, R. (April 17, 2025). US Energy Department Cap on Indirect Research Costs Temporarily Halted After Universities File Lawsuit. ChemistryWorld. Royal Society of Chemistry. https://www.chemistryworld.com/news/us-energy-department-cap-on-indirect-research-costs-temporarily-halted-after-universities-file-lawsuit/4021358.article?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- 18 National Science Foundation. (May 2, 2025). Policy Notice: Implementation of Standard 15% Indirect Cost Rate. https://www.nsf.gov/policies/document/indirect-cost-rate.

- 19 Spitalniak, L. (May 7, 2025). National Science Foundation Faces Lawsuit Over 15% Indirect Research Cap. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/national-science-foundation-faces-lawsuit-over-15-indirect-research-cap/747385/.

- 20 Unglesbee, B. (April 7, 2025). Judge Permanently Blocks NIH’s Plan to Cap Funding, Setting Up Appeals Battle. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/judge-permanently-blocks-nihs-plan-to-cap-funding-setting-up-appeals-batt/744647/.

- 21 Zhang, C. (April 16, 2025). Judge Blocks DOE Move to Cut Indirect Cost Rate. AIP FYI. https://ww2.aip.org/fyi/judge-blocks-doe-move-to-cut-indirect-cost-rate.

- 22 Higher Ed Dive. (August 18, 2025). Tracking the Trump administration’s moves to cap indirect research funding. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/tracking-the-trump-administrations-moves-to-cap-indirect-research-funding/751123/.

- 23 Unglesbee, B. (March 20, 2025). University of California Freezes Hiring as It Braces for Funding Cuts. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/university-of-california-hiring-freeze-trump-cuts-nih/743121/.

- 24 Svrluga. S. (March 3, 2025). Hiring Freezes, Fewer Grad Students: Funding Uncertainty Hits Colleges. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2025/03/03/universities-budgets-nih-indirect-cost-cuts/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- 25 Stabach, J. (February 15, 2025). Understanding NIH’s 15% Indirect Cost Cap: What Universities Need to Know. ARES Scientific. https://aresscientific.com/blog/nih-15-indirect-cost-cap-key-insights/.

- 26 Schwabish, J., & Axelrod, J. (July 9, 2025). NSF has canceled more than 1,500 grants. Nearly 90 percent were related to DEI. The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/nsf-has-canceled-more-1500-grants-nearly-90-percent-were-related-dei.

- 27 Quinn, M. (August 22, 2025). Supreme Court clears way for Trump admin. To cancel NIH grants related to diversity, gender identity. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/supreme-court-clears-trump-admin-cancel-nih-diversity-gender-identity-related-grants/.

Looking Ahead

The landscape of public higher education funding is uncertain. On a positive note, 38 states have surpassed recent pre-pandemic levels in total inflation-adjusted state appropriations; however, inconsistent enrollment data makes it difficult to determine whether per-student funding has truly recovered. Simultaneously, colleges and universities face mounting pressures beyond constricting state appropriations. With the federal cap on indirect cost reimbursements and the canceling and freezing of substantial research funding, institutions have faced new financial constraints and grappled with politically motivated mandates to alter or eliminate DEIA programs and navigate shifting free speech policies.

With state revenues in flux, complicated by tariff-driven inflation and federal unpredictability, many states are approaching the upcoming budget cycle with caution, and some are anticipating the need for mid-year corrections. These challenges, compounded by tightening institutional budgets, place public higher education in a precarious position. Looking ahead, the sector’s resilience hinges on not only flexible and innovative fiscal strategies but also a real commitment to protecting the core missions of public colleges and universities—education and research.

Note: NEA Research would like to thank ASA Research for preparing this brief.

Join NEA Higher Ed!