Key Takeaways

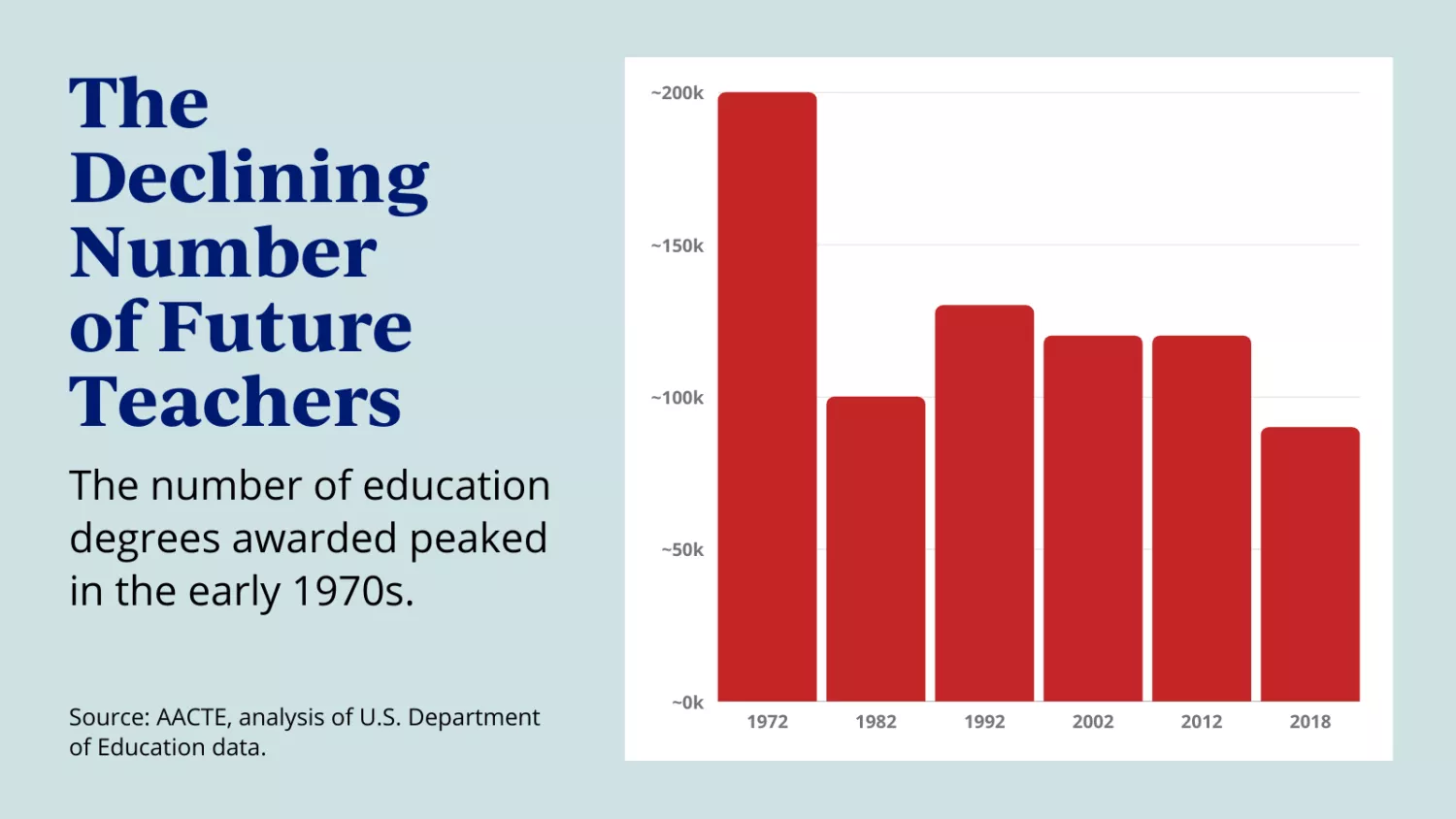

- The number of college students studying to become teachers is less than half what it was 50 years ago.

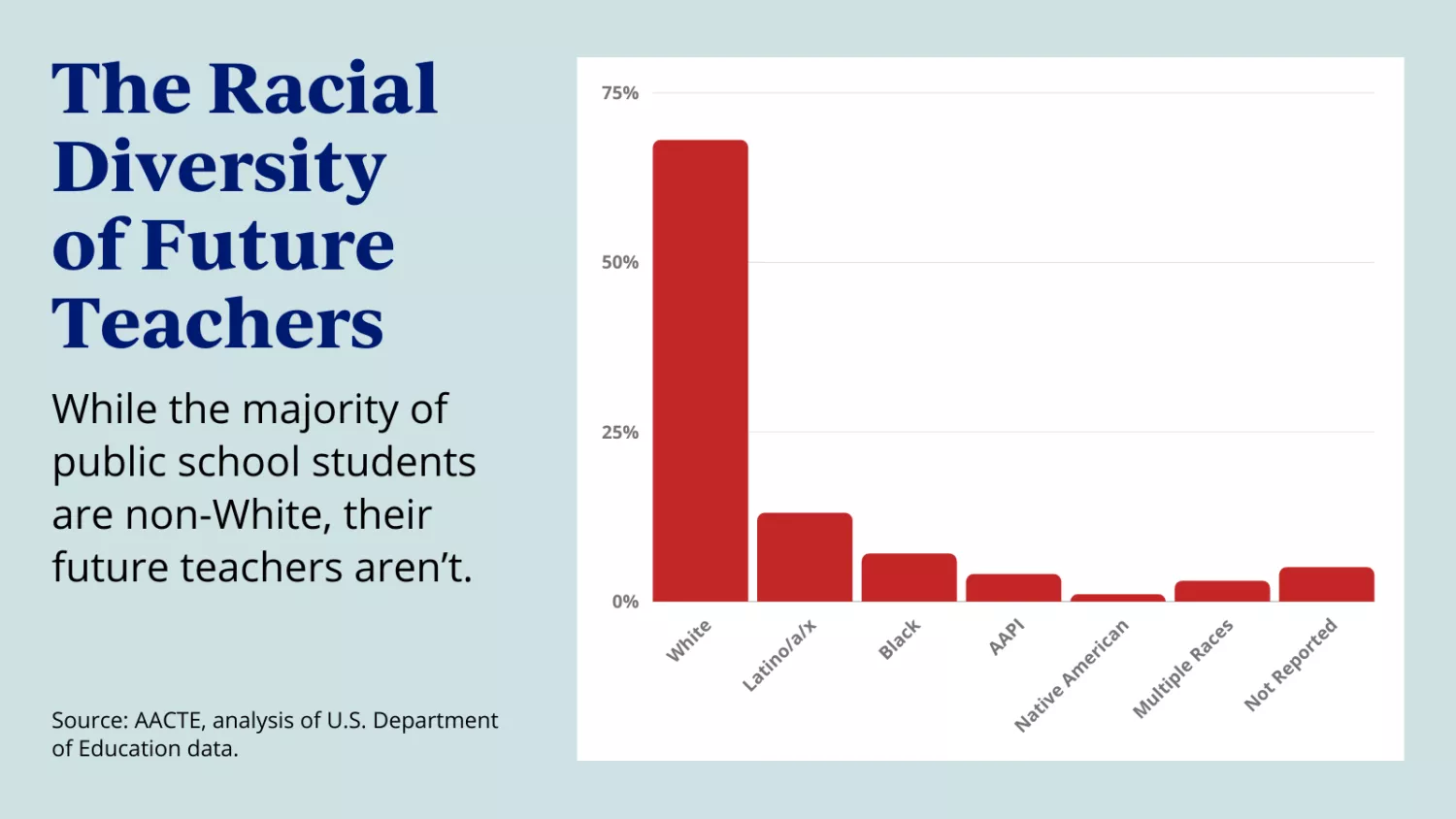

- Students pursuing education still tend to be more White than the overall student population. The only degree program with less diversity is agriculture.

- To counter these trends, NEA has been supporting "grow your own" educator programs, which support high school students who want to become teachers or paraeducators.

When it comes to the U.S. teacher shortage, the candle is burning at both ends. On the one hand, more stressed-out teachers are leaving the profession. On the other, the number of college students preparing to teach is still falling, according to a new report from the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE).

Among AACTE's findings:

- In 2019, U.S. colleges awarded fewer than 90,000 undergraduate degrees in education, down from nearly 200,000 a year in the early 1970s.

- In the last 10 years alone, the number of people completing traditional teacher-prep programs has dropped by 35 percent.

- The number of students earning degrees in science and math education—an area of high-need in U.S. schools—has fallen by 27 percent.

None of this is surprising to NEA members, who have been talking for many, many years about the escalating shortage, and what it will take to recruit and retain more teachers.

A lot of it, frankly, has to do with money. “The fact is teachers aren’t paid adequately—and everybody knows it and everybody talks about it,” says Cameo Kendrick, chair of the NEA Aspiring Educators. “These financial barriers are significant, especially as more non-traditional students consider [careers in] education. Like me, they have families and other responsibilities,” says Kendrick, who is raising two young daughters.

Kendrick also knows plenty of new and early-career educators who quit teaching this year. Last month, an NEA survey showed that a stunning 55 percent of current educators are thinking about leaving the profession earlier than they had planned—and this was before the spate of statehouse bills that would require teachers to submit all lesson plans, worksheets, reading activities, and other assignments a year in advance.

Now, as more college students opt for more lucrative, less stressful careers, who exactly will be teaching the nation’s children in the years to come?

“This is a five-alarm crisis,” says NEA President Becky Pringle.

Pay for Student Teachers Would Help

Next week, Kendrick and other Aspiring Educators will head to Capitol Hill to make the case for the Teacher Principal, and Leader Residency Access Act, a bipartisan bill that would enable college students to access federal work-study funds while they do their yearlong student teaching or residency.

[Join them in asking your U.S. Senators and Representatives to support the bill!]

“You’re working literally from 7:30 in the morning until late in the day, and it’s unpaid," says Kendrick. "At the same time, you’re still paying tuition, which is constantly increasing, you’re paying to take the certification exams they make you take, you’re paying for your license, and you’re paying to actually live! It’s literally not possible."

And, if you live in a rural area, the cost of getting from campus to school makes it even worse, she adds.

Growing Your Own Teachers

As the teacher shortage has been building for years, so has NEA’s work to increase the pipeline for new educators. One strategy is "grow your own" programs, which NEA Great Public School grants have funded in California, Connecticut, Florida, Nebraska, North Carolina and elsewhere.

Typically, these programs guide and inspire high-school students who want to teach in the communities where they live, explains Jame Cartwright, an NEA Higher Ed member and instructor at Nebraska’s Southeast Community College who teaches early-childhood educators in “The Career Academy,” a partnership between the college and Lincoln Public Schools.

The way it works, Lincoln high school students take Southeast college classes for two years, earning the necessary college credits to become paraeducators. If they qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, they pay nothing. (Students who live above the poverty line pay 50 percent fees.) When they finish, they get a guaranteed job interview with Lincoln schools, and dedicated help in transferring to a Nebraska university to finish their bachelor’s degrees.

“The program is seven years old, so we are just starting to see our K12 educators in the classroom—and it’s very exciting to see!” says Cartwright.

A Lack of Racial Diversity

The new AACTE data also shows a lack of racial diversity among future teachers. While 55 percent of U.S. students are People of Color, nearly 70 percent of prospective teachers are White, the AACTE analysis found.

In fact, education is one of the least diverse degree programs; in 2019, only agriculture was more White, AACTE found.

This lack of diversity isn’t just an issue for students of color: all students benefit from having teachers of color, research shows. While students of color have higher test scores and increased enrollment in advanced classes when their teachers look like them, White students also show improved problem-solving, critical-thinking skills, and creativity.

In Iowa City, Carmen Gwenigale is the first teacher of color for many of her students, she says. “Coming from Puerto Rico and Liberia, I could see myself in all aspects of my world, but my students [of color] don’t have that same experience,” she says. While students of color constitute nearly half of Iowa City’s students, non-White teachers represent just 6 percent of the workforce.

Now, part of Gwenigale’s job is to support Iowa City’s high school students who plan to become educators. Nearly 70 students are part of the district’s Educators Rising program; many are non-White and will be the first in their families to earn degrees. “Students understand right away [the value of diversifying the teaching staff.] Many were like, ‘I’m in tenth grade, and this is the first teacher of color I’ve had.’”