Key Takeaways

- When Columbus teachers went on strike earlier this year, their top issues had nothing to do with pay. They wanted safer classrooms, smaller class sizes, and more student access to art, music, and P.E.

- These non-traditional bargaining issues, which represent the collective concerns of parents, students, and educators, are taking center stage and often driving educators to strike—with community support.

- At the same time, negotiations are more likely to be open to the public. Parents and students can see exactly what educators are fighting for—and it's likely the same things that parents and students want.

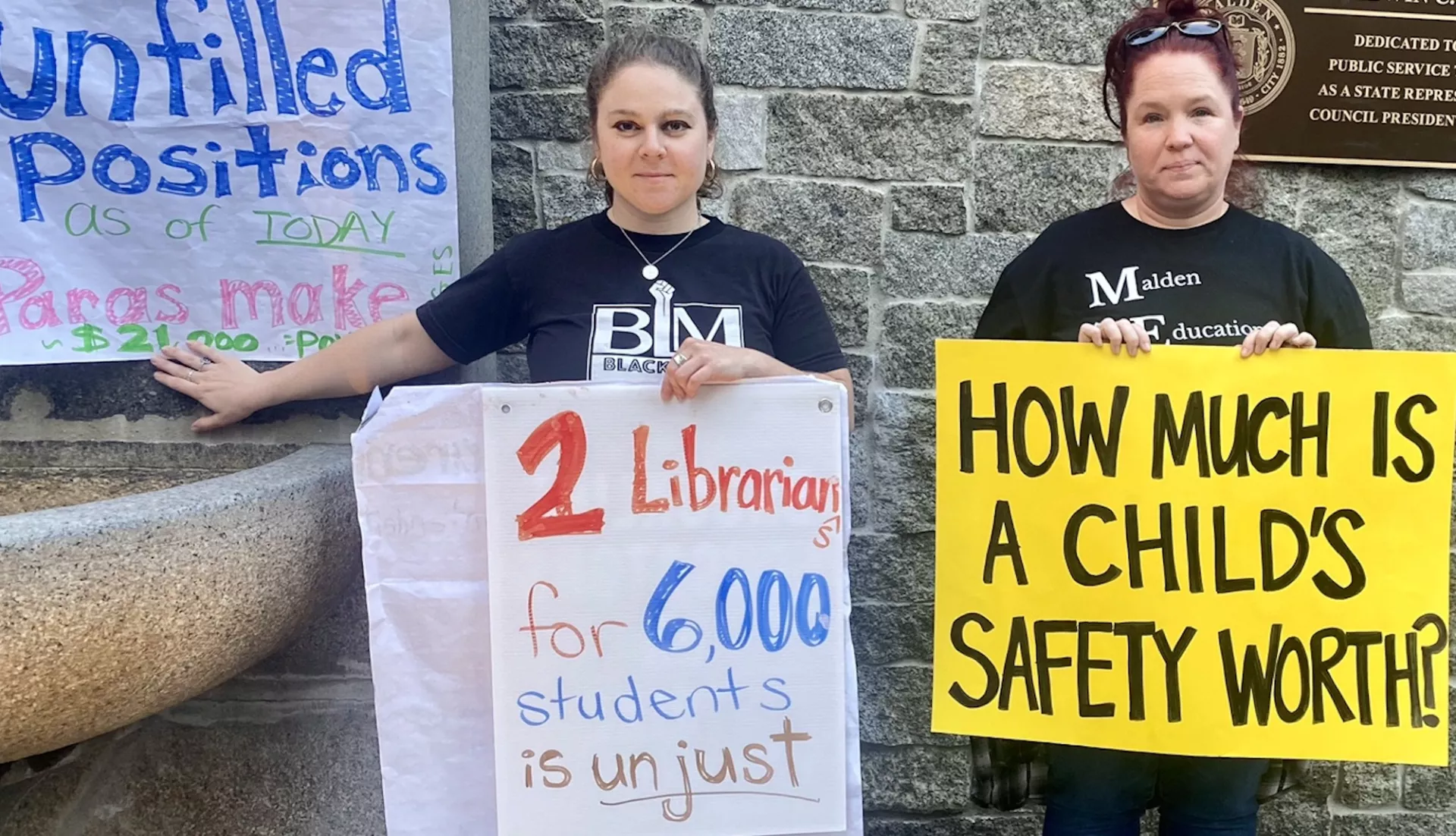

More than 100 people—educators and parents—packed the room on the evening of October 14 in Malden, Mass., for the third open session of contract bargaining between the town’s educators and the Malden School Committee.

And there they stayed, for 12 long hours, as the union team insisted on fair wages for the district’s lowest paid educators: the education support professionals who had put their own safety at risk during the COVID-19 pandemic, even as they earned scarcely more than $20,000 a year. In the end, the school committee’s bargaining team refused to help—and educators voted to strike.

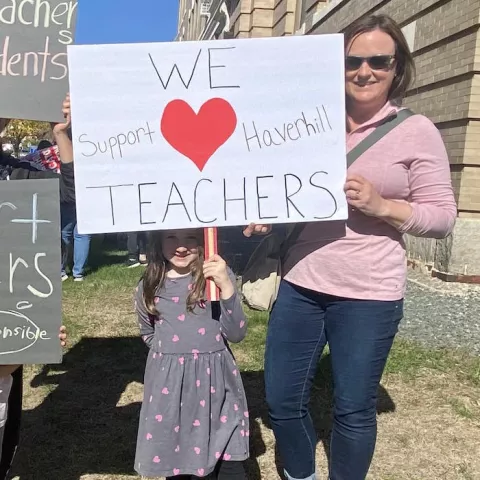

Meanwhile, the same night, a few miles away, educators in Haverhill, Mass., who also were bargaining a contract with their school board, reached the same conclusion: They would go on strike, too.

“Going on strike was scary,” recalls Malden Education Association President Deb Gesualdo. “But it was also a labor of love. We did it because we love our students and we love our community.”

This is what an educator strike looks like today: Malden and Haverhill educators were never alone on the line. Parents delivered cases of bottled water and boxes of baked goods. Students made signs and joined their demonstrations. Despite the inconvenience to parents and students, they supported educators. They trusted them to do what’s best for students and their community.

A few months earlier, when Seattle teachers went on strike for a week in September, mostly over smaller ratios in special-education and multilingual classes and ESP pay, it looked the same way. “I don’t think it’s unreasonable what they’re asking for,” a Seattle high school junior told The Seattle Times. “It’s not just about pay increases, it’s about student success and student education.”

The 21st Century Strike

While the 20st century teacher strike might have been about teacher pay only, the 21nd century strikes that have taken place across the nation—from Los Angeles to Denver to Minneapolis to Haverhill, Mass.—reflect the complex, often unmet needs of today’s students and classrooms, and the fact that educators are willing to go to the mat to get the schools that their students deserve.

The issues are broad, often including mental-health staffing, class sizes, school safety, racial equity, and more, and the actual bargaining is done in the open, with parents and community members watching. Consider Columbus, Ohio, in August, when the major issues were school safety and student access to music, art, and P.E.

“Going on strike was scary. But it was also a labor of love. We did it because we love our students and we love our community.” — Malden Education Association President Deb Gesuald.

Andy Jewell, NEA Senior Collective Bargaining Specialist, has been tracking educator strikes for several decades. He has seen how strikes have evolved in recent years—and notes a turning point in 2012, when 26,000 Chicago teachers, parents and students took to the streets for nine days. They talked about racial disparities. They talked about quality classroom facilities and pre-school access, and they pulled back the curtain on the for-profit charter schools that city officials had embraced. The Chicago Teachers Union’s vision for community schools was radically different and wildly popular—and communities across the nation took note.

“Chicago was a game changer,” says Jewell, and it was followed in 2015 by a Seattle strike in which educators talked about such non-traditional bargaining issues as class sizes and recess for all students, he notes. “There became a buzz. People began talking about ‘the schools that students deserve.’ It was the beginning of a transformation in how we bargain and what we bargain.”

In 2018, the big statewide strikes in West Virginia, Arizona and Oklahoma followed, with tens of thousands of educators and parents packing the streets around their state capitols, demanding state lawmakers invest in their public schools. But Jewell points to a tiny place—Ringgold, Penn., a town of about 1,000 people near Pittsburgh—where a 2017 strike showed just how things had changed.

What Happened in Ringgold, PA?

In 2017, in Ringgold, Penn., you could be a teacher with 10 years in the classroom, and you’d be earning less money than a new teacher in the district next door. But the issue that drove teachers to the picket line wasn’t pay exactly. It was respect. Did this community value the people who loved and taught its children?

Negotiations began in July 2016. “We made progress, then we didn’t make progress,” recalls then-Ringgold Education Association President Maria Degnan, who today works for the Pennsylvania State Education Association. More than a year after negotiations first began, in October 2017, teachers voted to strike—and then decided to tell parents why.

“My thought was, I’m a teacher! These parents know me,” Degnan recalled. When a colleague suggested a town hall meeting with teachers, parents, and local journalists, Degnan embraced the idea. Union members distributed flyers advertising the event, posted about it on Facebook, and then opened the doors to the local firefighters’ hall. “The day came and I’m thinking, we’re either going to get a lot of people or nobody,” says Degnan. “Well, every news station came. The local radio station came. And the fire hall was packed. I looked at my colleagues and was like, okay, here we go!”

Degnan started out by explaining how teachers had reached the breaking point. “When we started bargaining this contract, I was pregnant with my third child. I was able to point to him, to Tommy, and say, ‘Now he’s walking and talking! So, you know, this wasn’t a hasty decision!’”

For hours, Degnan stood up there, answering every question, honestly and fully. “I told them, ‘We want to go back to school.’ I told them, ‘We’re going to make sure your kids get everything they need.’” She also told them, “I’ve been teaching your children for 11 years. I have a master’s degree. And I make $45,100 a year.” Later, Degnan ran into a local Realtor who told her, “Any doubts I had were erased during that meeting.” Teachers had been transparent and honest. Board members weren’t talking at all.

The strike lasted 23 days. It began during the warm days of October and ended with snow on the ground. It wasn’t easy, Degnan recalls. But there was a lot of resolve on the picket line, and tremendous support from Ringgold parents. “There was a house across the street from one of the elementary schools and, every day, moms were there, grilling food for the teachers,” she recalls. “They opened up their bathrooms, let us park there. As it got colder, I said, ‘wow, you guys are troupers, still out there!’ and I remember so vividly one of the moms said to me, ‘as long as you’re out there, we’ll be here for you.’”

From Coast to Coast

Many of the educator strikes or walkouts that followed little Ringgold enjoyed the same level of community support and centered on issues that encompassed parents and students’ concerns. They include, to just name a few:

- West Virginia: Decades of neglect by state lawmakers led to a statewide, 9-day strike in March 2018. “I am proud that our members are refusing to sit silently by while lawmakers attempt to inflict further damage on the future of public education in West Virginia,” said then-NEA President Lily Eskelsen García, at the time.

- Arizona: No state had cut funding to public education more than Arizona. Teachers had textbooks that talked about the Soviet Union—not to mention class sizes of up to 48 students and individual counselor caseloads that topped 1,100. In April 2018, they staged the largest walkout in U.S. history, and eventually won historic increases in state education funding.

- Los Angeles: In 2019, a six-day strike involving 30,000 United Teachers of Los Angeles members ended with a settlement that provided students with more school librarians and counselors, 5-day-a-week school nurses, smaller class sizes, a commitment to reduce standardized testing, caps on special education caseloads, and investments in community schools.

- Denver: In 2019, the Denver Classroom Teachers Association broadcast their contract negotiations live on Facebook, enabling all to witness how much they were fighting to keep Denver teachers in Denver. Through striking, they achieved a fair and transparent salary schedule, which led to a 33 percent decrease in teacher turnover the following year.

- St. Paul, Minn.: In 2020, St. Paul educators went on strike to get more mental-health services for students, including school psychologists, school social workers, and counselors. And, in 2022, they were prepared to go on strike again to protect those jobs from cuts. An agreement was reached just minutes before the district was going to make the call to cancel classes.

- Minneapolis: In March 2022, Minneapolis educators went on strike for three weeks, eventually winning class-size caps and increased mental-health supports for students, including the guarantee of a nurse, school counselor, psychologist, and social worker at every secondary school, and one social worker at every building. They also won significant wage increases for ESPs.

- Columbus, Ohio: Class sizes that regularly topped 30; a lack of air-conditioning in many classrooms; and a lack of access to music, art, and P.E. These are the issues that drove Columbus Education Association members to strike in August—and they won on every point.

- Seattle: Seven years after their 2015 strike, Seattle Education Association (SEA) members went on strike again in September. The big issues? Educator workload in special education and multilingual classes, and baseline mental-health staffing for students. “Our strike shows the power that educators and community have when we unite and call for what our students need,” said SEA President Jennifer Matter.

“Nobody Will Make Less Than $30,000”

In two recent strikes, educators in Haverhill and Malden, located north of Boston, walked out in October—despite a state law that prohibits educators’ strikes and levies stiff fines against violators.

Both strikes had been building for years, maybe even decades. “We’ve been in austerity measures in Haverhill for 20 years,” says Haverhill Education Association President Tim Briggs. In the 2000s, Briggs saw colleagues laid off every year. Pay raises for educators? No. Not here. Educators sacrificed raises to keep jobs. Meanwhile, both Malden and Haverhill had increasing numbers of students with greater-than-typical needs, including growing immigrant populations. “We’re touted, in Massachusetts, as this great education state and we really are—but we also have one of the largest separations between the haves and the have-nots,” says Briggs.

This fall, Massachusetts educators knew the system had money. Indeed, the state got more than $1.8 billion in federal pandemic relief funds. When negotiations began, the unions issued a broad invitation: anybody was welcome to watch and see exactly what bargaining team members wanted for their schools, their students, and colleagues. Hundreds of educators, and many parents, showed up.

In Malden, all three bargaining units—teachers, ESPs, and assistant principals and others—had decided to bargain together for the first time. “It helped us realize the struggles we had in common, but it also highlighted the struggles we didn’t know about each other,” said Gesualdo. The struggle that captured every Malden educator’s attention, regardless of their own job classification, was ESP pay.

“Our paraeducators work with the most heavy-duty, medically fragile students,” says Gesualdo. “During the pandemic, they were in there diapering students, dealing with bodily fluids—and we really didn’t know, at that time, all the ways that covid could be transmitted. And there they are, feeding students, never able to be 6 feet apart.”

For this work, they were paid poverty-level wages. “We had our entire union stand up and say we’re going to fight,” Gesualdo recalls. Community members supported them. “I think the school committee thought people were going to be like, ‘oh, bad teachers, bad union,’ but parents supported us.”

The Malden strike lasted just a day, with the union winning improvements around class size and caseloads in special education, and a new parental leave provision that will enable new parents to take off 12 weeks and get paid. “That was huge!” says Gesualdo. But their biggest win? “Nobody will make less than $30,000 a year,” she says. “Depending on the hours you work, some ESPs will make up to $48,000.”

“Who Do You Trust?”

Meanwhile, in Haverhill, the school committee had hired a lawyer out of Boston who was hostile to labor unions—and put him in charge of contract negotiations. “We had an open bargaining session the Tuesday before our strike vote,” recalls Briggs. “More than 400 members showed up and watched this attorney, who essentially came to not bargain with us. Our members saw what was going on.”

That night, Haverhill’s strike vote passed with 97 percent approval. Immediately, the school committee attacked educators on social media. “But what was interesting,” Briggs says, “was that our parents answered—and they answered in support of teachers! [The district] ended up having to take down post after post on Facebook. They were getting beat up, beat up, beat up, and they didn’t understand why!

“We had put up a simple post: ‘Who do you trust? Do you trust your child’s teacher? Do you trust the people who you entrust with your most valuable human beings? Or do you trust the politicians who cut, cut, cut?”

The answer was clear when the Dunkin deliveries arrived on the picket line. “People were pulling up with waters, with coffees. Students stood on the line and spoke to the news… It was wild. It was overwhelming. It’s still overwhelming! We couldn’t believe how people showed up for us,” says Briggs.

In the end, Haverhill educators won. Their settlement, which ended a weeklong strike, doesn’t just include $10-14K pay increases so that Haverhill teachers can stay in Haverhill, it also includes health and safety improvements, a scholarship fund for Haverhill students to become educators, contractual commitments to racial justice, special education caseload limits, and a new planning time task force.

“We knew the strike was illegal,” says Briggs. “But we also recognized that in a city like Haverhill, where the underfunding has continued and continued and continued, we had to do something.

“We jumped and our community caught us."