Key Takeaways

- What’s happening in Minnesota right now is equal measures of horror and hope as educators and parents work to protect their neighbors from ICE.

- These NEA members are trusted to deliver diapers, drop off schoolwork, and even take out the garbage from families hiding in apartments.

- As ICE moves into other communities, Minnesota union members offer words of advice: get organized now.

The sun is setting and the temperature dropping to -22 when Minneapolis-area teachers Naomi Stenson and Lorna Plana lift the hatch on Plana’s minivan and load it with supplies for families and children afraid to leave their homes.

Rolling past homes still decked in Christmas lights, on eerily empty streets, the best friends deliver water, bags of groceries, and much more, all donated by educators and parents in their community. “It could be toilet paper, deodorant, cleaning supplies,” says Plana. “Or care bags of Play-Doh, art supplies, books, puzzles and games—because the kids need something to play with—and of course, we take work from teachers to continue students’ learning at home.”

Since early January, when U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) sent 2,000 agents to Minneapolis and St. Paul—a number that increased by another 1,000 two weeks ago and expanded ICE’s presence to the Twin Cities suburbs—immigrant families have been hiding in their homes, too scared to go to the grocery store or send their children to the school bus stop. Whether Native or newcomer, for Black, brown and Indigenous people in these school communities, including U.S. citizens, any trip outside of the home means risking harassment, assault, arrest, and detention by federal agents.

Children should be in schools learning, not hiding in fear from masked government agents, Minnesota educators say. The sight of another vacant desk, or an empty square on the kindergarten reading rug, is breaking their hearts.

It is also galvanizing them. While Minnesota educators are sad and scared, they’re also determined. And they’re doing what NEA members do: getting organized, standing in solidarity with parents, and making sure their children have what they need. Schools already are the hubs of communities. Now they’re also the grocery stories, laundromats, and even the banks, in some cases.

“Teachers and school staff are the ones who have trust with families. So many people want to help, but right now, we are the people who can do this,” says Plana, as she turns her minivan down another vacant street.

We’re not superheroes, adds Stenson. “We’re all just regular people…doing small things,” she says. “But those small things can add up.”

‘I'm So Proud of My Union’

On Saturday, January 24, federal agents shot and killed 37-year-old intensive-care nurse Alex Pretti as he filmed them outside a donut shop in Minneapolis. In early January, an ICE agent shot and killed Minneapolis mother Renee Good after she dropped off her 6-year-old at school. Last week, 5-year-old Liam Ramos was used as “bait” by ICE agents to lure his family members out of their home; he is now in a federal detention center in Texas, a move that counters all child-protective protocols. The kindergartner is one of four students in Columbia Heights, Minn., a suburb of Minneapolis, apprehended last week by ICE agents who have been roaming neighborhoods, circling schools, and following the district’s yellow school buses, school officials said.

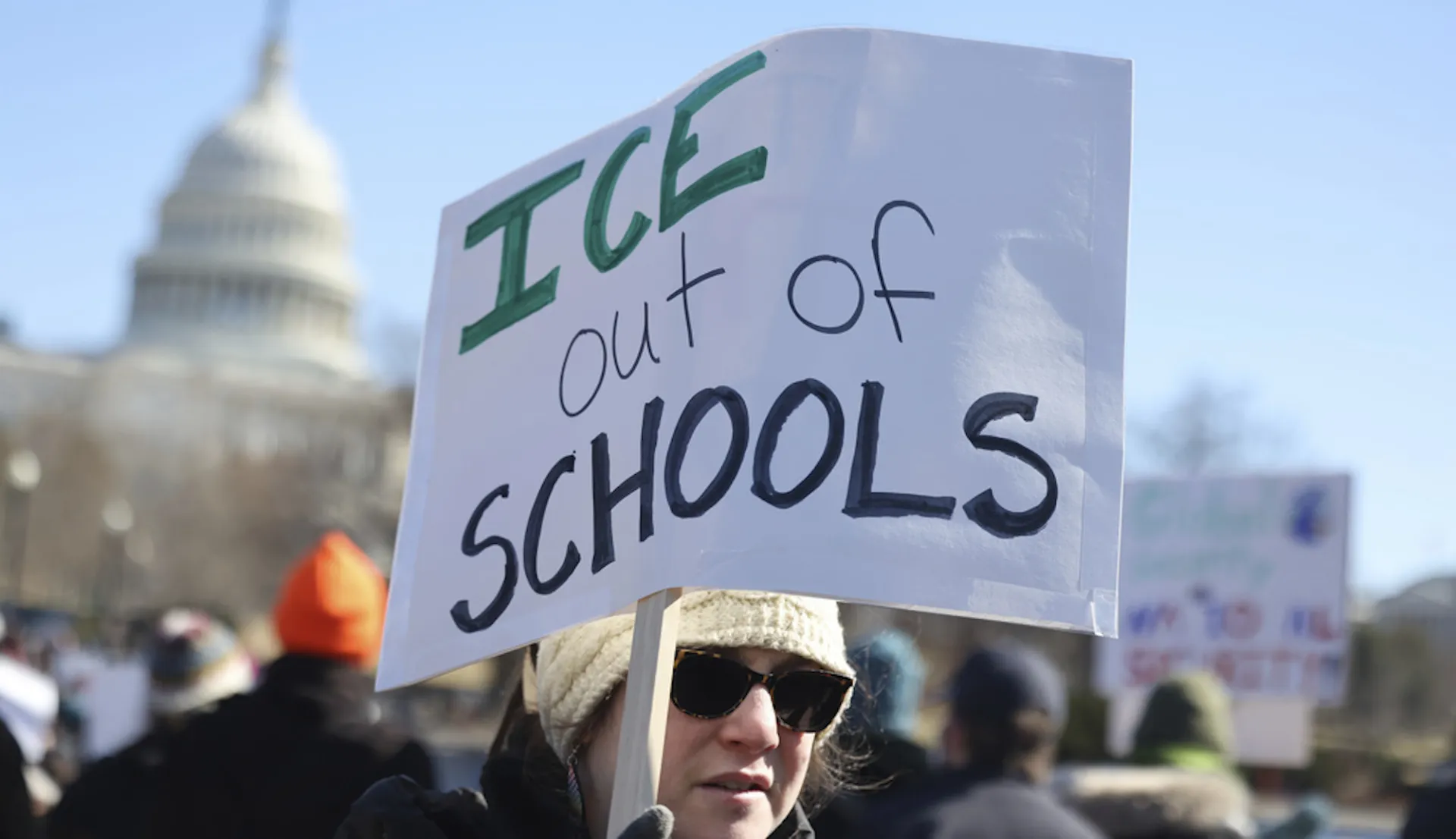

This trauma is why NEA President Becky Pringle has demanded ICE immediately end its occupation of the Twin Cities and elsewhere—and keep their agents out of our schools, hospitals, and places of worship. “Federal terror has no place in public education or in a democracy,” she says.

It’s also why union members are fighting back. Every day, as “these acts [by ICE agents] grow more heinous,” notes a St. Paul pre-kindergarten teacher, the response by educators and parents to ICE also grows. “As things have gotten worse, as they’ve gotten more horrific and traumatic, the community response also has been more powerful and uplifting.”

“I am so proud of my union right now,” says Jenny Konkel, an educational assistant in a transitional program for 18- to 22-year-olds and secretary of the St. Paul Federation of Educators (SPFE). “I see all of these people coming together at the last minute, fighting for our students… it’s amazing.”

Through SPFE, union members, parents, and neighbors are activating safety patrols on the streets around schools during drop-off and dismissal, raising funds, coordinating donation drives for food and diapersand more, and even walking dogs, dropping off clean laundry, and removing bags of kitchen garbage from homes where the moms and dads are too afraid to wheel a bin to the curb.

Thousands of people have reached out to SPFE to ask how to help. A week ago, union leaders and staff trained 400 people, in just two days, to serve as school patrol volunteers. The union also has coordinated workshops for immigrant parents on how to complete the legal paperwork they need to keep their children safe, in case the parents are detained or deported.

“This isn’t the work that we went to school for, but these students are like our kids. We love them and want to take care of them in any way we can,” says Konkel. “If they need food, we’re going to feed them. If they need clean laundry, we’ll find a way to get it to them. This is the work in our hearts.”

Educators on Safety Patrols

On a recent afternoon, the “feels-like” temperature is negative 30 degrees. And still, St. Paul educator and parent Jill Moe gets out of her car, dons a yellow safety vest with a big red heart on the back, and stands on a frigid West Side street corner with a plastic red whistle tucked into a pants pocket.

Moe, an educational assistant in St. Paul’s Early Childhood and Family Education Program for babies and toddlers, has been a member of SPFE’s coordinated safety patrols for the past few weeks. “I’m watching, looking for cars that might be ICE,” she says. If she sees one—and she hasn’t yet—she will blow three short blasts on her whistle, alerting the nearby school’s principal to get students into a safe location.

One block away is parent Alex Schluender, who coordinates this school’s patrol. “It was easy to stand up a parent patrol here. We put out a call and got 50 people out… not just parents, but neighbors who just want to help,” he says.

Inside the ring formed by school patrol officers like Moe and Schluender is science teacher Megan Hall, working bus duty near the school’s front entrance. She and her colleagues also have whistles and specific protocols to protect students from a possible ICE operation.

“It’s absurd. It’s so strange. When I first started teaching, we had fire drills and tornado drills. Then, unfortunately, we started to have to develop safety drills in case of an active shooter in the school or neighborhood,” says Hall. “Now, we have to develop safety protocols in case our own government shows up to hurt or kidnap our students? I never dreamed I would have to do something like this.

“Of course, I will. I love my kids. I will be here for them.”

The World is Watching

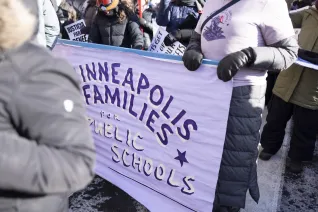

The Twin City educator unions in Minneapolis and St. Paul have strong community relationships, which deepened after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020 and through the battle for racial and social justice in their neighborhoods. They are also part of a rich network of labor unions in the area.

On the morning of January 23, educators met at the local carpenters’ union to make art and drop off donations for families. Piles of canned vegetables and stacks of Pampers filled dozens of collapsible tables. One St. Paul school counselor, an immigrant himself, brought his 8-year-old son, who carried a package of art markers for the children who can’t get out.

Quote byMegan Hall, Teacher, St. Paul

They were thanked by Education Minnesota president Monica Byron who told them: “When educators stand together and refuse to let the fear and chaos happening around this country come into our schools, we need to be proud… You are part of a profession that shows up for people. You are part of a union that has your back. You are making a difference, and you are exactly what our students and communities need right now.”

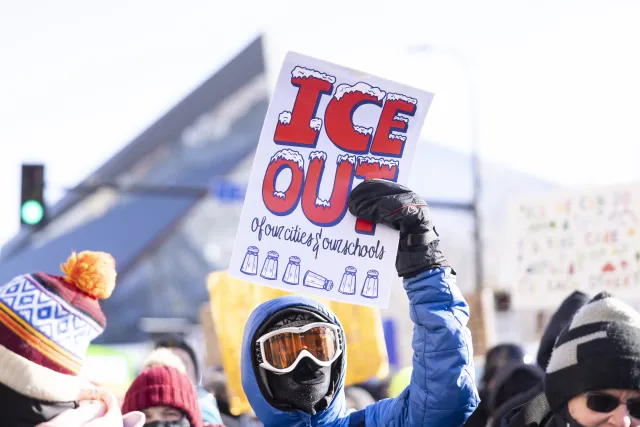

Later, these teachers, counselors, administrators, and educational assistants would join an estimated 50,000 marchers in the streets of Minneapolis, braving the coldest day of the year to demand that ICE leave Minnesota and stop terrorizing their neighbors. “My students are terrified...They're trying to learn and instead they're wondering, 'Is it safe to be here? Am I going to be kidnapped? Am I going to be targeted for the color of my skin? Am I going to be coming to campus someday and end up in detention in a country I've never been to?' Nobody can learn under conditions like that," said a local faculty member, a sign in hand. "It's not right. None of this is right."

These Minnesota educators know the world is watching them. They also know that when ICE leaves the Twin Cities, they likely will occupy another community. They have a message for educators in those places.

Reach out to parents and other like-minded organizations now. Ask parents what they’re going to need and figure out how to set up systems to help. Other parents will want to help you. Just ask them, says Stenson, who single-handedly started her delivery system with a single Facebook post that “skyrocketed,” she says.

“Get organized,” says the St. Paul pre-kindergarten teacher. And stick together, says Konkel. “Solidarity is an amazing thing.”

Listen to this St. Paul Counselor on Why You Should Help, Too.

Elapsed time: 0:00

Total time: 0:00Keep ICE Out of Schools Protest - January 23, 2026

Jenn Ackerman

Jenn Ackerman

Jenn Ackerman

Jenn Ackerman

Jenn Ackerman

Jenn Ackerman