Key Takeaways

- Students experiencing hardships coupled with few school interventions or resources can at times escalate school violence.

- Educators need help now and their unions are stepping in to help stop the attacks.

- Community schools also offer promising solutions.

Edyte Parsons begins her class at 8:45 a.m. with a check-in, where she learns how her fourth graders are doing or what they did the previous evening. She then moves on to morning work—projects students can easily accomplish—followed by math. Mornings are one of the best parts of her day, she says.

At about 10 a.m., Parsons, an elementary school teacher in Kent, Wash., starts to see the warning signs.

A student gets up from his seat, walks around the class, and begins to provoke other students, until one eventually snaps back. The roving student storms out of the room, slams the door, and joins the fifth and sixth graders during their recess and lunch break.

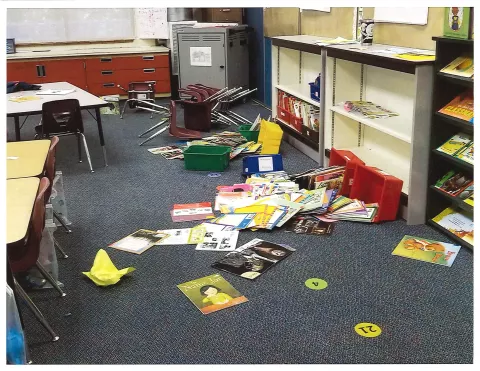

Parsons’ lessons have been interrupted by much worse over her 10-year career in two different school districts. Desks have been shoved or tipped over. She’s been hit and kicked. Today, as a union building representative, she gets called in when her colleagues experience similar outbursts or physical attacks from students.

Last year, Parsons says, “a 5-year-old hit, scratched, spat on, and kicked at least six adults.”

The child was dealing with trauma: His mother had almost died and was revived in front of him. But there were few interventions or resources available to help curb the child’s behavior.

A Growing Concern

From March 2020 – June 2021, the American Psychological Association surveyed nearly 15,000 pre-K–12 teachers, administrators, school staff, and counselors about their experiences with physical threats and attacks from students and parents.

One-third of the teachers reported being threatened by a student within the year, including verbal threats, cyberbullying, intimidation, or sexual harassment; and 29 percent reported at least one incident from a parent. Fourteen percent of teachers said they had been victims of physical violence from students.

The Kids Are Not OK

“One of my students punched me,” says a Texas physical education (PE) teacher who wishes to remain anonymous.

“You could see it coming,” she recalls, explaining that the student had a history of threatening other teachers, too. In one instance, the student had told an educator he was going to shoot her brains out and then stomp all over them.

“She was terrified to go to work,” the PE teacher says of her colleague.

For the PE teacher, getting punched was the last straw. She called the police and the middle schooler was arrested. At the time, she says, administrators tried to convince her not to make the call.

“It’s tough,” she says. “He had problems at home.”

A few years later, the PE teacher ran into the student, who had moved on to high school.

“He came up to me, asked if I remembered him. I said, ‘Yeah. I remember you.’ He told me, ‘I wanna apologize ... it was not a good time for me. I learned my lesson. … I’m sorry.’”

Educators, principals, and parents understand that kids are having a hard time, so it’s difficult for them to agree on how to discipline students, how to provide them the additional support needed, and where school districts can find the funding needed to get students the help they deserve. Still, all agree that despite the challenges, if nothing is done, the behavior issues in schools may only get worse.

The Consequences of No Consequences

Credible threats get downplayed or ignored, says Tim Martin, president of the Kent Education Association (KEA).

Last year, he says, a middle school student in his district cornered a teacher in the stairwell.

“He made a gun with his hand, put it to her head, and threatened her,” Martin says. “She was scared to death. She went straight to the office and reported it.” But nothing happened.

According to Martin, school officials reported that the student had a ketchup packet in his hand and that he did not make a hand gesture in the form of a gun.

Because administrators are afraid of getting fired, they try to change the verbiage so the threat doesn’t have to be rated so high, Martin explains. But he says behaviors are “out of control.”

Norma De La Rosa, a retired teacher and president of the El Paso Teachers Association in Texas, can attest to this.

She has fielded calls from educators who want administrators to follow student discipline policies for threatening and violent behaviors.

“But this seems to be the common result: Kids do things like … bring weapons to school,” De La Rosa says. “They’re reported, and nothing gets done to the students, because they’re back in class the next day.”

Quote byEdyte Parsons, Fourth-grade teacher

Some Parents Have it Hard, Too

Educators know that parent involvement and support is crucial to a student’s academic success. But sometimes, that parental support is hard to come by.

Last year, Parsons says, two-thirds of parents attended conferences—eight students were not represented. “That’s a lot,” she says.

Parents have their own struggles. Many parents work more than one job and can’t make it to a conference, some are single parents with shiftwork, every student has a unique background, and getting parents to participate in school activities can be difficult, especially in situations where parents refuse to engage.

Parsons tells of a parent who “went off” on the principal saying: “Don’t ever contact me. Don’t do anything unless my son is going to the emergency room.”

Why would she say that, Parsons questions who later learned the harsh reality of what this child’s parent, and many others, are dealing with in their own job.

“Her boss was angry that she was on the phone and told her that the next time she was on the phone, she was fired,” Parsons explains. “What kind of pressure is that on the parent? I’m not faulting parents all the way around, … but what are we supposed to do?”

Something Must Change

One way is to demand from politicians and those who control school budgets to invest in hiring more counselors and interventionists. This would allow trained specialists to fully dedicate their time to students, just so long as they’re not assigned to lunch duty, too.

Parent and community liaisons are also critical positions. These professionals can help build relationships with families and find organizations that can provide services to students when they need them.

Another way is through your union. Laws that protect teachers from harassment and violence while on the job vary by state. Your local and state unions can help ensure discipline policies are being followed and can advocate on educators’ behalf.

Quote byTim Martin, President, Kent Education Association

Collective Bargaining Can Help

KEA has been able to bargain for strong language in their contract to ensure safety protocols are followed. These protocols document the number of incidents that occur at a school. No students are named, just the number of incidents and the teacher.

This sets in motion a series of actions to ensure educators are supported and protected.

If two or three plans to curb behavior have failed, Martin explains, the union can request that someone from the central office sit in a classroom with all parties involved until a plan is devised.

“At first, principals were afraid that if they reported things, they were going to get in trouble,” he says. “But once word gets out that the union has stepped in and has made some headway in getting help for the student, and in turn everybody else, then more administrators tend to step into the ring with us.”